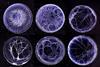

Whiskey webs could snare counterfeiters

Unique patterns formed by whiskey residues could aid investigations into imitation liquors

Unique patterns made by drops of whiskey offer a way to identify different liquor brands – and might provide a tool for authorities investigating counterfeited products.

When mechanical engineer Stuart Williams left Kentucky to go on sabbatical, he took with him a case of whiskey that he’d be given by friend from the local Brown–Forman distillery. His destination was the North Carolina lab of colloid scientist Orlin Velev, and when Williams met his new colleagues, the whiskey proved to be more than just a delicious icebreaker.