University students across the UK are enjoying a mixture of online and practical learning as departments adjust to new restrictions

After a turbulent end to the last academic year, university chemistry departments spent the summer making plans for the return of their students and a new socially distant way of teaching. With their first term over halfway through, and the pandemic second wave in full force, staff and students are getting used to the new normal.

After a turbulent end to the last academic year, university chemistry departments spent the summer making plans for the return of their students and a new socially distant way of teaching. With their first term coming to a close, and the pandemic second wave in full force, staff and students are getting used to the new normal.

The first hurdle for chemistry departments has been coping with the fallout from the A-level grading fiasco. With the switch to grading based on teacher’s predictions, more students than usual attained the grades they needed to attend their first choice universities. This has left some departments massively oversubscribed and others nearly empty. University College London (UCL), for example, has had to expand its intake from 160 to 240. ‘Even if we return to normal [next year], we’ve got a problem for the next four years,’ says Dewi Lewis, deputy head of UCL’s chemistry department. But Suzanna Kean, head of chemistry at the University of South Wales has the opposite problem. ‘We have had a massive decrease in student numbers … I’ve only got seven chemists in my first year.’ That’s less than half the number she would usually expect.

For some departments higher grades have meant that students who would normally start on a foundation year were accepted straight onto degree programmes. The University of Leicester’s student numbers were boosted in this way, giving them 95 first year students, around the number they would normally recruit, although the market for its foundation year decreased. But, adds undergraduate admissions tutor Richard Blackburn, ‘we [also] didn’t see a mass exodus [of] the students that we had got through insurance routes.’

Covid-19 itself does not seem to have deterred students from starting degrees, according to Panagiotis Manesiotis, director of education at Queen’s University Belfast’s school of chemistry and chemical engineering, although he adds, ‘we did spend a lot of time panicking and worrying about it’.

Blended learning

Over the summer universities put in place new ‘blended learning’ approaches. Each university has taken a slightly different route but most are pre-recording lectures to be delivered online. The chemistry department at Queen’s has maintained one of the highest proportions of face to face teaching of any department in the university, with about 50% of student time being on campus. ‘There isn’t a lot of appetite to move to fully online at this stage, and students seem to enjoy both,’ says Manesiotis.

Teaching online has been hampered by poor internet connections in some places. Kean has adjusted lectures accordingly. ‘It’s all been really challenging, we’ve tried to keep away from presenting new information in live sessions,’ she says. Leicester have gone for a similar approach, plus, says Blackburn, ‘we’ve had a bit of a head start’ – their staff are already experienced at teaching online, having a campus at the Dalian University of Technology in China.

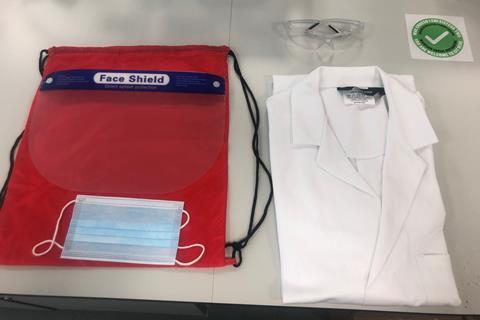

Preparing teaching labs has been a huge task says Haralampos Miras, director of learning and teaching at the University of Glasgow chemistry department. ‘Occupancy of the lab area is [now less] than 20%, allowing a two metre safe distance between individuals at all times. Additionally, we allowed enough time for disinfecting the lab area between two consecutive lab sessions while we have one day per week dedicated for deep cleaning.’ The small student numbers at South Wales have made lab work much easier, but students wear full PPE and screens have been erected throughout the labs in addition to being marked up for social distancing.

Many universities have cut down face to face practicals to the essential. Queen’s has subscribed to an online experiment platform. ‘We will use it mainly for preparing the students and giving them an idea of what to expect,’ says Manesiotis. The Drylabs forum, convened before the summer for all chemistry departments, is also helping to share online resources to replace face to face labs. For example, explains Kean, ‘one of my team is using an HPLC simulation, to actually simulate running an HPLC machine and generating the spectrum from that, and then challenging students to analyse it’.

Lab-in-a-box

UCL has taken a different route and is doing all of its teaching online in its first term. ‘We have a large overseas contingent and getting a flight from certain places is actually impossible,’ says Lewis. The new arrangements have meant some significant shifts to the degree structure, with more courses being continuously assessed, freeing up time for more practical work later in the year.

UCL chemistry students will not be missing out on practical work though. ‘Their entire labs have gone to the lab-in-a-box,’ says Lewis, ‘the brainchild of Professor Andrea Sella’. Over the summer Sella and other UCL colleagues designed what Lewis describes as an ‘exploration kit’ that is being sent out to first year chemists, with a modified version also going to UCL’s life scientists.

The kit contains no chemicals – those needed, such as salt or vinegar, can be obtained locally – making it possible to export the kit to students overseas. It contains a micropipette, jewellers’ balances, a pH meter, a thermocouple and a multimeter. ‘It’s mainly based around measurement, you make something, you measure something,’ says Lewis. The first set of experiments involves baking several cakes using different recipes and then comparing their properties. Another challenges the student to cool water to the lowest temperature possible in their kitchen. There are experiments on chirality and growing crystals: ‘Some of them are just insane!’ jokes Lewis.

So far, the students seem very excited by their early Christmas present. ‘They’ve been sharing unboxing videos,’ says Lewis, ’we hope they’ll [continue to] engage with it.’ The kit has also made UCL staff think hard about the purpose of practicals. ‘There’s a lot of stuff in there that we shy away from doing in the actual lab, because it looks like it’s messing around. But it isn’t. It’s discovering all those [fundamental] things that people discovered using a pipette, a thermocouple and a pH meter.’

Christmas comes early for @uclchemlab_14 students. Enjoy the laser pointer measurements and observations this week. The fog in the evenings adds to the fun. https://t.co/HsPl64rvQz

— UCLChem_Lab_14 (@uclchemlab_14) November 6, 2020

Covid contingencies

Departments who have chosen socially distant face to face teaching are being vigilant about the spread of Covid-19, particularly those in high risk areas. ‘There were some cases involving chemistry undergraduate students in the [Glasgow University] student residences, says Miras, but ‘so far there [have been] no cases [linked to] face to face [teaching] activities’. At Leicester, Blackburn admits, ‘none of us are expecting to get to the end of the year and not have students who have had to miss [labs], or indeed staff’. The university has set up its own on-campus Covid-19 testing programme to detect asymptomatic infection, which is open to all students and staff.

It is safer for students to be on campus where you can monitor social distancing

Although Wales entered a 17 day ‘firebreak’ in October, there had been relatively few cases within the student body at the University of South Wales and their on-campus labs were to continue through the lockdown. However due to a staff Covid-19 case, the technician team was forced to isolate, shutting the labs for two weeks. They intend to return to their lab schedule. ‘It is actually safer for [students] to be on campus where you can monitor the social distancing … than perhaps what we hear is going on in some of the student halls,’ says Kean.

The lockdown in England does not stop educational activities, but Blackburn says Leicester University as a whole has now raised its Covid-19 precautions so that only teaching that can’t be replicated online continues face-to-face. For chemistry this means some tutorials will move online, although all practical classes will continue.

But all universities have made contingencies for a potential full lockdown that would prevent all face to face teaching and labs. Departments with modern well-ventilated labs such as Leicester may be able to hold out longer than others. ‘If we [have to] go further than that, then we have some time that we’ve reserved at the end of the academic year [to complete labs],’ says Blackburn. Departments also have plans to take more practicals online and at Queen’s University Belfast, Manesiotis says every supervisor has been asked to provide online or literature-based back-up projects for final year students.

Flexible benefits

The new normal has brought some pleasant surprises to both students and staff. The absence of face to face lectures in many universities has made time for other types of learning support. ‘[They are having] lectures with [additional] dedicated Q&A sessions attached to them online, and there are discussion boards that run as well,’ says Blackburn. Manesiotis has found that ‘the academics get the benefit of the students being more prepared … a lot of students are sending us messages that say, ‘we really enjoy the flexibility [of online learning]’. However Lewis adds that students can be unwilling to turn on their cameras in online sessions and teaching multiple black boxes can be disconcerting.

At Glasgow, ‘the initial feedback that we have received is that the students are coping pretty well with the new mode of delivery. They are engaging with the online material, [and] interacting using the peer support groups we have set up for them,’ says Miras. A general cause for concern with remote teaching had been a lack of peer support, particularly for first years, but Kean says ‘behind the scenes they have actually been establishing Facebook or Whatsapp groups.’

Some of the teaching changes might stick. Lewis is hopeful that less emphasis on lectures will lead to a more active style of learning in future, where students are challenged to think. ‘I wish we hadn’t had to do it in four months. But, if you had said to us, take three years to try to convert this into that, we would have taken three years!’

The additional work has been stressful for academic staff. ‘People have had to drop tools on their research,’ explains Lewis. ‘By half term, quite a few people, myself included, were running on vapours.’ But Kean has high praise for her departmental colleagues, who have ‘been absolutely brilliant’.

With the course of the pandemic remaining unpredictable, it remains to be seen how the rest of the academic year will unfold. ‘We’ve got a plan A, we’ve got a plan B and we’re starting to work on plan C … but I think the phrase “fingers crossed” springs to mind,’ says Lewis.

Meanwhile, in the US…

Rebecca Trager

Of nearly 300 US university presidents recently surveyed about the state of their institutions amid the pandemic, more than half – 55% – reported a drop in their enrolment for the autumn 2020 term relative to the previous year. 23% of the respondents to the American Council on Education survey said their autumn 2020 enrolment stayed about the same as the previous year, while 22% said the figure had increased. In addition, approximately 70% of the presidents at US public and private four-year higher education institutions reported that international student enrolment fell.

Nearly half of the presidents reported that revenue from tuition and fees remained about the same as during the previous academic year. However, 73% reported a decrease in income from auxiliary services like event hosting and parking fees, 61% stated that their university lost money from room and board, and 54% registered a reduction in endowment earnings or gifts.

To respond to these financial challenges, 61% of the respondents revealed that their institutions have implemented hiring freezes, and 54% reported halting increases in employee compensation or salary. Further, 21% reported already introducing employee pay reductions, and 28% said they had already laid off staff.

Unfortunately, the survey results indicate that difficult times are likely to continue for US academia. In their responses, 38% of the university presidents said they anticipate that their institution may need to implement employee layoffs in the next 12 months, which they estimate could affect approximately 10% of their total workforce. In addition, 28% of them said their university may need to furlough employees in the next 12 months, and 16% indicated pay reductions might be necessary.

No comments yet