5.15pm: That’s all folks!

Thanks for joining us today and we hope you’ll join us again on Friday 7 October as we discuss the three new laureates and their discoveries in our free webinar. The Nobel prize has been a wonderful showcase for chemistry once more. Congratulations again to the worthy winners… We’ll be aiming to post our feature providing an in depth dive into the work that won the prize with interviews with the new 2022 chemistry laureates next week.

5.11pm: Have questions about the prize? We’ve got the answers.

Want to know what exactly click chemistry is? Or how it’s employed by bioorthogonal chemistry? Then our explainer is for you. We take you through who the laureates are, how they came up with their Nobel-winning discoveries and why they’re important for chemistry and society.

5.02pm: I imagine Sharpless is just waking up right about now!

Barry Sharpless right now on finding out he has to get on a plane to Sweden in December to pick up yet ANOTHER chemistry #NobelPrize #chemnobel. pic.twitter.com/I566t8X05X

— Patrick Walter (@PatDWalter) October 5, 2022

4.09pm: It just clicked

Interestingly, Google’s Ngram viewer, which records how often a word or phrase appears in a book, shows a similar trend to Web of Science when looking at bioorthogonal and click chemistry.

3.57pm: Sign up for the Chemistry Nobel webinar – we have some great guests confirmed

Join us for a special free Chemistry World webinar as we talk about this year’s Nobel prize in chemistry. The guests confirmed so far include Nicholas Riley, a postdoctoral fellow working in the Stanford lab of chemistry Nobel prize winner Carolyn Bertozzi. Nicholas will offer some insight into the world of a Nobel prize-winning lab and what it’s like to work with Carolyn, as well as telling us more about their research. We also have Phillip Broadwith, business editor at Chemistry World who will be explaining more about the science behind this year’s prize and insights into the reaction of the chemistry community. More guests will be confirmed in the coming days so check back here for more information.

3.50pm: Read all about it

Our news story on the three new chemistry Nobel laureates is out now.

2.53pm: The rise of click and bioorthogonal chemistry

Using Web of Science we’ve created a plot of publications in journals that mention either bioorthogonal or click chemistry. The term click chemistry was coined back in 1998 and bioorthogonal chemistry didn’t appear until 2003. It’s interesting to see that the number of mentions of click chemistry in scholarly publications has started declining. It’ll be interesting to see if the Nobel prize reinvigorates interest in this incredibly powerful technique for connecting molecules.

2.42pm: Ever wondered what it’s like to win a Nobel prize?

Here Ben Feringa tells us what it was like when he won the chemistry prize back in 2016. One thing’s for sure, laureates all agree that their lives are never the same again.

2.14pm: Past performance can predict future performance

As we saw earlier today (10.39am update) prestigious awards like the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Centenary Prize or the Wolf Prize can signal that this researcher could be in line for a Nobel prize one day. Bertozzi did indeed win the Wolf Prize in Chemistry earlier this year, as well as the Welch Award in Chemistry this year too. It’s notable that these major prizes came the same year as the Nobel – often the Nobel prize committee are considered to be more conservative than other award panels and reward work that was conducted far longer ago. For instance, last year’s winners for organocatalysis did their pioneering work over twenty years ago and John Goodenough (2017 chemistry laureate) did his groundbreaking work on lithium-ion batteries in the 1970s.

Since Barry Sharpless already won the chemistry Nobel prize in 2001, it can be a little harder to untangle whether the awards he’s received are click chemistry related or for his other work on epoxidation, for example. Sharpless did win the Priestley Medal in 2019 – the American Chemical Society’s highest award – but this is for services to chemistry and is more a lifetime award. Sharpless did win the Wolf Prize in Chemistry in 2001, but this wasn’t for click chemistry, but asymmetric catalysis. He did also win the Centenary Prize in 1993, but the term ‘click chemistry’ wasn’t even coined until 1998.

Morten Meldal’s work has gone under the radar somewhat when compared with Bertozzi and Sharpless and this is notable in the number of awards he’s received. Click chemists are likely to know who he is, but chemists in other fields may not know his name. Meldal hasn’t received any of the major chemistry prizes (being based in Denmark, and not one of the huge US universities, may not help when it comes to getting noticed by award committees) so winning the chemistry Nobel prize and having his work recognised by the top prize must be very welcome!

1.03pm: A popular winner

Many people had Carolyn Bertozzi down as their pick for this year. She’s been a popular choice as her use of click chemistry within living cells has enabled a revolution in how cells can be monitored and targeted. In fact, her work has been used to localise cancer drugs to where they can cause the most damage to tumours – this is already being tested in trials in humans now.

OK, we’ll soon know, but my Nobel guess this year is @CarolynBertozzi

— PeO Norrby 🇸🇪❤️🇺🇦 (@PeONor) October 5, 2022

Voters in Stuart Cantrill’s poll can give themselves a pat on the back too

3 weeks today (Oct 5th), the 2022 #chemnobel will be announced, so it's time for my annual #ChemTwitter poll! What topic do you think *will* (not should) claim the prize? (Leave comments suggesting what might win if none of the options in the poll...); RTs appreciated!

— Stuart Cantrill (@stuartcantrill) September 14, 2022

Bioorthogonal and click chemistry had some of the best odds from Paul Bracher @ChemBark – and definitely deserves kudos for getting all the winners and putting them together on the same award. You can pick my lottery numbers next time…

The Official @ChemBark Odds/Predictions for the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry #ChemNobel pic.twitter.com/s0CF74Lxgg

— ChemBark (@ChemBark) September 28, 2022

12.37pm: So close…

Spare a thought today for M G Finn of Georgia Tech. He did his PhD with Sharpless (then at MIT) on asymmetric epoxidation – the area in which Sharpless won his first Nobel prize – and was tipped by Clarivate for the Nobel for click chemistry as one of their citation laureates back in 2013.

M.G. Finn now maybe the chemist closest to two Nobel Prizes without winning one. pic.twitter.com/m2rQeT6Yss

— ChemBark (@ChemBark) October 5, 2022

12.27pm: Nobel stories

You can find all our Nobel prize coverage in one handy place.

12.23pm: What do you do when your lab’s still closed and your teammates aren’t there to celebrate with you?

Just in!

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 5, 2022

First selfie from our 2022 #NobelPrize laureate in chemistry @CarolynBertozzi. Congratulations! pic.twitter.com/kuremcRIaN

12.13pm: More reactions

This is from Tom Brown, Professor of Nucleic Acid Chemistry, Departments of Chemistry and Oncology, University of Oxford

“The concept of click chemistry, initially pioneered by Barry Sharpless 20 years ago aided by his colleagues Valeri Fokin and M.G. Finn, has been transformative in many areas of chemistry, materials science, biology and medicine. It has given rise to new highly functional materials, has catalysed important pharmaceutical developments and has been influential in many areas of chemical biology.

The archetypal click reaction is Cu(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), the copper-catalysed version of the original Huisgen reaction. The CuAAC reaction makes exclusively 1,4-disubstitted 1,2,3-triazoles. It can be looked upon as a molecular ‘superglue’ or ‘molecular lego’ to join molecules together. It was discovered simultaneously by Sharpless and Meldal. It is an extremely efficient reaction, and crucially it is orthogonal to most other chemical reactions, and can be carried out in most media including water. These properties, particularly the fact that it is ‘invisible’ to other functional groups an molecules, make it incredibly flexible and broadly applicable. Applications are almost endless, for example it has been of enormous value to our own research in the nucleic acids field.

The remarkable work of Carolyn Bertozzi has given rise to new types of click reactions that do not require copper catalysis, termed ‘Bioorthogonal click chemistry’. This concept can be used in applications where the CuAAC reaction and related metal ion catalysed reactions are not possible due to the toxicity of the metals.

An example of Bioorthogonal click chemistry is the SPAAC reaction (Strain-promoted alkyne-azide cycloaddition) involving the reaction of an azide with a strained cyclooctyne. Importantly Bertozzi’s work enables click reactions to be done in living systems. It enables the visualisation of molecules in living cells and organisms, the study of disease processes, and development of new drugs including improvements in drug delivery. It has very been used to great effect in the study of glycans (polysaccharides) that play a major role in all essential functions of the human body, including the immune system.

This is Sharpless’s second Nobel Prize in Chemistry, a stunning achievement. Anyone who knows him will testify that he is a unique character who is remarkably imaginative and passionate about chemistry.”

David Pendlebury, Head of Research Analysis at the Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate, said: “Clarivate selected the three new Laureates in chemistry as probable Nobel recipients in 2013, 2015, and 2019. Click chemistry, pioneered by Sharpless and Meldal, has already had tremendous impact and application across many fields and especially in the pharmaceutical industry. Bioorthogonal chemistry is a powerful method for studying biological processes and will enable more precise clinical therapies. Of course, we should mention this is the second Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Sharpless, who received the 2001 Prize. Until now, only Frederick Sanger won two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, in 1958 and in 1980.”

Clarivate has now selected 13 researchers as laureates that went on to win chemistry Nobel prizes.

12.04pm: A little known fact about Barry Sharpless

A cautionary tale for us all here. Sharpless lost his sight in one eye after a nasty lab accident.

After yesterday's discussion on wearing appropriate #PPE in the lab at all times I went in search of #chemnobel Barry Sharpless' story on how he lost an eye. Here's his cautionary tale... #SafetyFirst #chemistry pic.twitter.com/nG9Oeq1UTn

— Patrick Walter (@PatDWalter) January 31, 2018

11.47am: Ig Nobel awards

Funnily enough Barry Sharpless was the one giving out awards last month at the annual Ig Nobel awards that reward research that can be charitably called ‘unusual’. He presented the medicine Ig Nobel to a group of Polish researchers for their work on reducing the side-effects of a chemotherapy drug. The team, led by Marcin Jasiński from the Medical University of Warsaw, showed that ice cream is just as effective as ice cubes for alleviating oral pain associated with melphalan treatment prior to bone marrow transplants. Jasiński and his colleague Anna Brodziak offered special thanks to the hospital cafeteria for donating free ice cream to the patients involved in their study.

11.41am: Well chemistry Twitter, have you?

I've used a click reaction in my research:

— Dr Nathan Kilah (@ChemistryNathan) October 5, 2022

11.39am: Sharpless twenty-one years ago

He’ll have to dust off the black tie again and see if it still fits!

Barry Sharpless has just become the fifth individual to be awarded two Nobel Prizes.

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 5, 2022

He follows in the footsteps of double #NobelPrize laureates John Bardeen, Marie Skłodowska Curie, Linus Pauling and Frederick Sanger.

Sharpless was awarded the chemistry prize in 2001 and 2022 pic.twitter.com/iQg0FL79zg

11.37am: Nobel webinar

Quick reminder – we’ll be a hosting a free webinar at 1500 BST (1600 UTC) on Friday 7 October taking in all the reactions from around the world to the awarding of the chemistry prize to Carolyn Bertozzi, Morten Meldal and Barry Sharpless. It’s sure to prove a popular prize with chemists who have tipped both Bertozzi and Sharpless for some years (US bias perhaps), while Meldal is less well known (although Clarivate picked Meldal previously – and Sharpless and Bertozzi too). Join us and special guests as we talk about who won, why, and what it means for chemistry. Whether you’re delighted or disappointed, we’d love you to join us and share your thoughts on the announcement.

11.31am: More on clicking

Click chemistry has been an extremely important concept in chemistry for over twenty years now. Consequently we’ve covered it a number of times in Chemistry World. This first feature length article focuses on the development of click chemistry itself and the philosophy behind it, while another feature length story looks at how click chemistry started moving into biology back in 2010.

11.26am: Reactions are starting to come in now

This is from Professor Gill Reid, the president of the Royal Society of Chemistry

”I am so pleased to see that Carolyn Bertozzi, Morten Meldal and Barry Sharpless have won this year’s chemistry Nobel for their pioneering work in bioorthogonal and click chemistry and offer them my warmest congratulations. Their work has incredible potential for applications in human health and medicines and the possibilities are incredibly exciting.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry always underlines that this is a unique discipline, both combining the theories and the ideas of the discipline, together with that ability to manipulate atoms and molecules on that very, very tiny scale. That provides huge opportunities to create better materials and bring solutions to some of these really serious global challenges – across energy and environmental sustainability to healthcare and food security.

It’s also important to note, as in fact many Nobel laureates are keen to do themselves, that like this year’s award, chemistry is very much about making connections. Teamwork plays a vital role across scientific disciplines and the people who receive these glittering awards all have many colleagues and collaborators – sometimes across international borders – with whom they share these accolades, and I pay tribute to them all.”

11.22am: Stay with us

Don’t go away just yet. We’ll be bringing you a story on today’s chemistry laureates along with an explainer putting the importance of click and bioorthogonal chemistry in context. That’s alongside all the reactions from the community to today’s worth winners.

11.18am: Nobels on video

Morten Meldal, along with Sharpless, developed the chemistry tools that would allow chemical reactions to be performed in cells without killing them. Here he is celebrating his win.

First celebration! @ChemKUniversity @UCPH_Research @NobelPrize pic.twitter.com/pQAytyP3U2

— Jiwoong Lee (@TheLeeLab_Chem) October 5, 2022

Sharpless is based on the west coast US so it’s still the middle of the night there. Having already won a Nobel prize before perhaps he won’t bother to get and celebrate yet!

11.11am With have an interview with Sharpless

We’ll be bringing you our interview with Sharpless later today.

11.05am: Carolyn Bertozzi in her own words

Bertozzi has spoken to us previously about her work pioneering work. She’s also given us an insight in her personal life and that she dreamed of being a rock star before inventing the field of bioorthogonal chemistry.

11.03: Bertozzi is on the line

The bioorthogonal chemistry pioneer is talking the chemistry prize committee. It’s the middle of the night where she is and the shock has left her ‘barely able to breathe’ she says.

10.57am: Two wins

So Barry Sharpless becomes the fifth person to have won two Nobel prizes. He is also only the second person to have won two chemistry prizes. The only other person to have achieved that remarkable feat is Frederick Sanger, who won the 1958 and 1980 chemistry Nobel prizes for his work on protein structure, particularly insulin, and on DNA sequencing, respectively. Sharpless won his first Nobel prize in 2001 for research on chirally catalysed oxidation reactions, specifically what has come to be known as Sharpless epoxidation.

Sharpless has been tipped for some time as a serious candidate for his work on click chemistry – a powerful tool for linking molecules together simply. This win combines with Bertozzi’s much more recent work on bioorthogonal chemistry, which has allowed chemistry to be carried out in cells without damaging them.

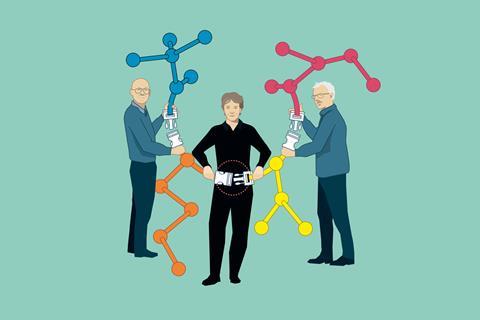

10.50am: Many congratulations to the winners! Well deserved

The winners developed new ways to join molecules together, including in living cells themselves.

BREAKING NEWS:

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 5, 2022

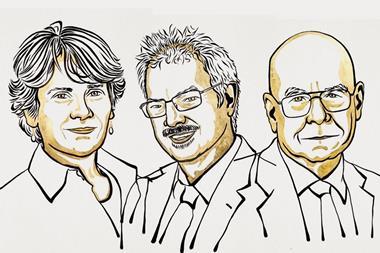

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the 2022 #NobelPrize in Chemistry to Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Morten Meldal and K. Barry Sharpless “for the development of click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry.” pic.twitter.com/5tu6aOedy4

10.47am: It’s bioorthogonal chemistry and click chem!

That’s two chemistry Nobel prize wins for Barry Sharpless now! And Carolyn Bertozzi, who has been hotly tipped for a number of years now

10.45am: We are a go-go

10.44am: Here we go?

Doors opening in the grand room at Karolinksa.

10.39am: Prize predictions

The first chemistry Nobel prize was awarded in 1901, but it certainly wasn’t the first scientific prize. The Copley Medal is awarded by the UK’s Royal Society and is the longest continuously running award of its kind in the world, and one that can be given for a discovery in any scientific field. The first was given to Stephen Gray in 1731 for his work on electricity and it’s been given pretty much every year since. But of these longer running and particularly prestigious prizes, which has had the most success when it comes to awarding a researcher who then goes on to win a chemistry Nobel prize?

The Centenary Prize, given by the Royal Society of Chemistry (full disclosure: it also publishes Chemistry World) since 1949, has the best record with 28 awardees who went on to win a chemistry Nobel. This prize rewards ‘outstanding chemists, who are also exceptional communicators, from overseas’. Perhaps being adept at talking about your work is a big factor in getting it noticed and rewarded – something that isn’t always considered when it comes to who wins prizes. The Centenary prize has recognised famous name chemists such as synthetic legend RB Woodward, unraveller of carbon fixation in photosynthesis Melvin Calvin and inorganic maestro HC Brown before they went on to win a chemistry Nobel. As the years have gone on the number of ‘hits’ has gone down though (presumably the incredible increase in the size of the field and the number of people working in it is a factor), but recent picks that have gone on to win a Nobel include 2016 supramolecular superheroes Jean-Pierre Sauvage and Fraser Stoddart (Ben Feringa, the other winner of the 2016 Nobel has won a Centenary prize but after his Nobel), olefin metathesis chemist Robert Grubbs and lithium-ion battery pioneer John Goodenough (100 this year!). It’s worth noting that the Centenary prize has recently gone to some chemists who have been hotly tipped to win a Nobel, including Omar Yaghi for metal–organic frameworks. (Clarivate’s data crunching approach – not shown as it’s not a scientific award as such – has correctly picked 10 chemistry laureates since 2008.)

This year’s Centenary Prize winners are Michelle Change at University of California, Berkeley (the UC system of 10 campuses is a Nobel powerhouse with 14 chemistry prizes) for her work on biosynthesis and biocatalysis, Joseph Francisco at the University of Pennsylvania for his application of computational chemistry to atmospheric research and Catherine Murphy at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for her research on gold nanocrystals.

10.35am Ten minutes to go – the live feed from Sweden has begun

10.33am: What wins a Nobel prize?

We’ve put together word clouds of the citations for all the Nobel prizes in physics, medicine and chemistry. Perhaps it’s just my imagination but the word cloud for chemistry seems more focused on a few items than physics and medicine, which appear more diffuse and spread across a greater number of topics.

10.30am Fifteen minutes to go

Provided the Nobel Foundation can get hold of the winner(s)…

10.27am: Poll results are in

With only a few hours left to go until the 2022 Nobel prize in chemistry, what are your final picks for this year's winning research?

— Chemistry World (@ChemistryWorld) October 5, 2022

10.24am: Beware prank callers though!

"I bet $1000 that this isn't happening!"

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) August 27, 2022

Our 2021 chemistry laureates @dmac68 and @ben_list tell us how they found out they had been awarded the #NobelPrize.

Who will find out they have been awarded this year's chemistry prize? pic.twitter.com/4TOTxBtI89

10.22am: Stand by your phones!

Chemists! Keep an eye on your phone because today The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences will make the decision about the #NobelPrize in #Chemistry 2022. pic.twitter.com/V3BC8nBtWw

— Vetenskapsakademien (@vetenskapsakad) October 5, 2022

10.22am: Prize money

The Chemistry World team has been chatting about why the Nobel prize has been so influential over the years and why it is seen as the premier science award. A big part of the reason the world sat up and took notice of the Nobels, we decided, was cold, hard cash. When the prize was founded in 1896, winners could expect to receive around $40,000 – $1 million in today’s money. (The prize money this year is 10 million Swedish krona (£809,000).) This made it far and away the biggest award for any science prize. Other medals and awards may have a longer and more illustrious history when the Nobels came onto the scene, but they’re now the name everyone knows. Other prizes have come along recently with even larger cash awards, but it remains to be seen whether they can capture the public imagination like the Nobel prizes have.

10.17am: Join us on Friday

Quick reminder – we’ll be a hosting a free webinar at 1500 BST (1600 UTC) on Friday 7 October taking in all the reactions from around the world to the awarding of the chemistry Nobel prize. Join us and special guests as we talk about who won, why, and what it means for chemistry. Whether you’re delighted or disappointed, we’d love you to join us and share your thoughts on the announcement.

10.15am: Disruption or merely carry-on as normal?

The question of whether Nobel prize-winning research is actually unusually innovative or just happens to hit the right topic at the right moment has been tackled head on by a Chinese team. They used a tool from previous research that aimed to measure the disruptiveness of a research topic – that paper found that smaller teams often deliver highly disruptive or novel ideas, whereas larger teams tend towards further development of current theory. Armed with this disruptive index the Chinese team looked at Nobel-winning work and found – surprisingly – that this research is not necessarily more disruptive than benchmark research from the same era.

10.11am: The subfield race

In recent years the chemistry Nobel prize has come to be dominated by the biochemistry subfield. This is perhaps unsurprising as the interface between biology and chemistry is where a great deal of exciting discoveries have been made. Think of Crispr gene-editing (2020), artificial evolution of enzymes and antibodies (2018), DNA repair (2015) and G-protein coupled receptors (2012). With the Nobel prizes trying to cover all the sciences, the omission of a clause in Alfred Nobel’s will to set up a biology prize means, just maybe, there’s more overlap than there would be if a separate prize existed for the biologists. Last year’s win by Ben List and Dave MacMillan for organocatalysis means two more for the organic chemists, still chasing biochemistry. In my opinion they’re not going to catch them though.

10.09am: RNA breakthrough rapidly becomes hottest new tip for a Nobel

The RNA technology that has gone on to be used to produce a whole new class of vaccine – mRNA vaccines – and was deployed in record-breaking time in the pandemic, seems almost certain to get the Nobel nod one day. Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman have already won 2020’s life science Breakthrough prize for their dogged work on RNA technology. (The Breakthrough prizes, set up by Silicon Valley tech billionaires including Mark Zuckerberg and Sergey Brin, are the best remunerated science prizes in the world at $3 million.) RNA therapies were not always seen as a promising avenue, but their perseverance – particularly Karikó who faced a number of professional setbacks for her single-minded pursuit of the technology including demotion – paid off in the end as the world’s first RNA vaccine became a game changer during the Covid pandemic. The pair also won last year’s Lasker clinical award. The Lasker awards have been running since 1946 and are often a good predicator of Nobel prize success, although the awards are more geared towards medicine so this may be a sign that the chemistry prize is not the one for them. Weissman and Karikó have also won this year’s Tang Prize and Japan Prize. It’s also of note that the Oxford-AstraZeneca team has won the Royal Society’s prestigious Copley Medal for its work developing a Covid vaccine.

10.01am More prize predictions but approximately 100% more adorable

Lawrence picks the Laureates is back for year # 3! He passed up the chance to pick click chemistry for the 3rd year in a row and went with @kkariko’s advances that led to the mRNA vaccines. #chemnobel pic.twitter.com/I3PhHpLbYG

— Frank Leibfarth (@Frank_Leibfarth) October 4, 2022

9.58am: Prize predictions

We’ve been asking some Nobel laureates who and what might win the chemistry Nobel prize…

9.54am: Want to see a Nobel laureate thrown into a pond? Of course you do!

Svante Pääbo, who won the medicine price for his work sequencing hominin genomes, has some students that are rather overexcited by his win. Question is, is that now a gene pool? I’ll get my coat.

In case anyone needs to see a @NobelPrize winner get tossed into a pond :)

— Benjamin Vernot (@melanoidin) October 3, 2022

Congratulations, Svante! pic.twitter.com/C6jnHO8nCr

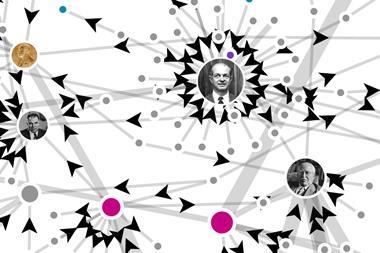

9.50am: Top secret: Who nominates whom for Nobel prizes?

The Nobel committee is pretty secretive about how they pick the winner(s) each year, but after 50 years have passed they release the details of who was nominated by whom. Anyone can browse the nominations archive, which is great for looking at individuals, but not so useful to pick up any overall themes. So we’ve taken the whole database of chemistry prize nominations and turned it into some visualisations for you to enjoy poking through. We’ve produced network diagrams for each decade of nominations up to the most recently available year, 1970. We’ve also picked out a couple of key rivalries and two heavy hitters of the early–mid 20th century, Linus Pauling and Robert Woodward. And we looked at how women got nominated across all the science Nobels – it’s just as bad as you might imagine: only 67 nominations went to women over the first 70 years of the Nobel prizes.

Below is the network diagram for 1961–70 that is dominated by synthetic organic chemistry legend RB Woodward.

9.47am Quick crossword while you wait…

(Also on its own dedicated page.)

This crossword is powered by Exolve, © Viresh Ratnakar

9.39am: Educated guesses

Up against Clarivate’s data-led approach are guesswork and gut instinct. This has led voters on Nature’s Stuart Cantrill’s poll to go for Carolyn Bertozzi for bioorthogonal chemistry. Bertozzi and her pioneering work performing reactions within living cells without disrupting them has become a popular tip for the chemistry Nobel prize. She won the Wolf Prize in Chemistry earlier this year, often seen as a good predicator of future Nobel success.

3 weeks today (Oct 5th), the 2022 #chemnobel will be announced, so it's time for my annual #ChemTwitter poll! What topic do you think *will* (not should) claim the prize? (Leave comments suggesting what might win if none of the options in the poll...); RTs appreciated!

— Stuart Cantrill (@stuartcantrill) September 14, 2022

ChemistryViews has also polled its readership and the wisdom of the crowd says the next chemistry laureate will be a male biochemist from North America. Specific researchers that receive a namecheck in the poll include Shankar Balasubramanian for his work on next generation DNA sequencing (biochemist from the UK), John Jumper (American) for the use of AI to predict protein structure and Janusz Pawliszyn (Polish analytical chemist working in Canada) for the development of analytical microextraction techniques.

Chemistry & Engineering News has also run its annual livecast talking to top chemists about who their picks for the Nobel nod are. mRNA vaccines and Drew Weissman and Katalin Karikó were the hot pick, but bioorthogonal chemistry and radical polymerisation also got a look in. You can watch again right now.

Odds on favourites from Paul Bracher @chembark too…

The Official @ChemBark Odds/Predictions for the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry #ChemNobel pic.twitter.com/s0CF74Lxgg

— ChemBark (@ChemBark) September 28, 2022

9.35am: Analytical predictions

Data-crunchers at Clarivate have once again been making their predictions for Nobel success. Over the years they’ve succeeded in picking out 64 Nobel prize winners (this includes economics too) – although rarely in the year that they win. They picked one of last year’s winners Ben List in 2020 though, which is pretty good. This year, they’ve picked out a number of researchers based on their citations, including flexible electronics pioneer Zhenan Bao, who we spoke to in 2019.

9.27am: Where do chemistry laureates live and work?

Having said the majority of Nobel laureates come from Europe and North America you can explore here where they lived and worked. Here you can see where chemistry laureates were born and where they moved to to carry out their Nobel-prize-winning work (red indicates where they were born, while yellow is where they did their prize-winning work). Comparing pre-second world war with post (drop-down menu) the increase in researcher mobility is stark. This is a global trend now with academics rarely staying in one institute or country for their entire career anymore.

Last year’s chemistry laureate, Dave MacMillan, is one of five that emigrated from the UK to the US and did their prize winning work there. How many laureates have left your country for another to carry out their most important research?

9.17am: Ethnicity and the Nobel prizes

Just as the chemistry Nobel prizes have been dominated by men, they have also been dominated by men of white European descent. It is notable, though, that 36 chemistry prize winners were or are of Jewish descent. The rise of Japan as a scientific power following reconstruction after the second world war has seen also eight chemistry laureates with east Asian heritage. So far, only two chemistry laureates have had Indian or Chinese heritage; however, this is something that is certain to change as these two nations that make up two-fifths of the world’s population continue to expand their science base. But to date the vast majority of laureates have come from and worked in Europe and North America – and there’s not change to that this year. All the laureates are from Europe (3) and North America (1).

Inside Science did something interesting in 2019, by creating composite images from photos of all the medicine, physics and chemistry Nobel prize laureates. The faces they generated all look eerily similar.

9.10am: Progress, right?

But things have surely changed a lot for women in science in the past 120 years? Haven’t they? Some countries now boast equal numbers of men and women working in science, and far more women are reaching the highest levels of science. Problems remain, however, with concerns over a ‘leaky pipeline’ where women depart research at all stages of their career in greater numbers than men, social pressure for women to be the main carer for children and the persistence of attitudes that science is ‘for boys’. Having said all this, the picture when it comes to women winning a science Nobel prize over the last 20 years still looks little different to that of the whole history of these prizes. Clearly a long way to go before parity is reached.

9.03am: Women and the Nobel prizes

With the Nobel Foundation’s tweet about Marie Curie – the first female winner of a chemistry Nobel prize – it seems like a good time to look at how women are doing when it comes to the prizes. After 2020’s chemistry Nobel prize where two women won, normal service was resumed in 2021 with two men taking the award. In fact the science Nobel prizes across the board went to men. This has been repeated again so far this year so it’s down to chemistry to introduce a bit of diversity this year in the sciences. Far more prizes have gone to men than women since the Nobel prizes were founded in 1901. This is unsurprising though, given that women were barred from even attending universities in many countries for a significant portion of the 20th century, without even mentioning the other barriers that were placed in their way by a scientific enterprise wholly dominated by men. (Our Significant Figures series chronicles some of the discrimination women working in science faced and how they overcame it to make serious contributions to our knowledge of the world).

9.00am Who will it be?

When Marie Skłodowska Curie was awarded the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry she became the first person ever to receive two Nobel Prizes.

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 5, 2022

Who will join Marie Skłodowska Curie as a chemistry laureate? Find out when the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry is announced today.#NobelPrize pic.twitter.com/1yYta9sM0b

8.54am: Nobel prize crossword has landed!

If you’re trying to pass the time before today’s Nobel prize announcement, why not make a cup of tea and have a crack at our Nobel-themed crossword.

8.50am: The chemistry Nobel in numbers

113 chemistry prizes awarded since 1901

188 scientists have been made chemistry laureates

1 person has won the chemistry prize twice – Fred Sanger for his work on protein structure specifically insulin (1958) and nucleic acid sequencing (1980)

6 The number of double Nobel prize winners across all categories. John Bardeen won the physics prize twice (1956 and 1972), Marie Curie won the physics prize in 1903 and chemistry prize in 1911. Linus Pauling won the chemistry prize in 1954 and the peace prize in 1962 and, as above, Sanger won the chemistry prize twice. The International Committee of the Red Cross has won the peace prize three times (1917, 1944 and 1963) and the United Nations High Commission on Refugees has won the peace prize twice (1954 and 1981).

7 women have been made chemistry laureates

35 The age of the youngest chemistry laureate – Frédéric Joliot (1935) for radioactive element synthesis

97 The age of the oldest chemistry laureate – John Goodenough (2019) for the creation of lithium-ion batteries

8 The number of times the chemistry prize has not been awarded either due to war or no suitable discovery being recognised (the last time this happened was 1933)

8.43am: Quick reminder

You can find all our Nobel prize coverage in one handy place.

8.40am: Who do you think is going to win?

Everyone loves to make an informed guess at what’s going to win the next chemistry Nobel prize. Let us know in the poll what topic you think it might be and if you pick ‘Other’ tell us below the line who you think it might be…

With only a few hours left to go until the 2022 Nobel prize in chemistry, what are your final picks for this year's winning research?

— Chemistry World (@ChemistryWorld) October 5, 2022

8.31am: Reacting to the Nobel prize

We’ll be a hosting a free webinar at 1500 BST (1600 UTC) on Friday 7 October taking in all the reactions from around the world to the awarding of the chemistry Nobel prize. Join us and special guests as we talk about who won, why, and what it means for chemistry. Whether you’re delighted or disappointed, we’d love you to join us and share your thoughts on the announcement.

8.23am: The Nobels so far this year

So, a quick recap of what’s happened so far in the Nobels. On Monday Svante Pääbo won the medicine or physiology prize for his work sequencing ancient human relatives and his contributions to understanding the evolution of humanity and extinct hominins. Tuesday was the turn of the physics prize and that went to Alain Aspect, John Clauser and Anton Zeilinger for their research on quantum entanglement that laid the groundwork for the development of quantum computing – something that has caused great excitement in the fundamental chemistry community.

And what happened last year? Well, last year’s winners were Ben List and Dave MacMillan for their work on asymmetric organocatalysis. MacMillan spoke to us recently on the joys of handing out his medal to everyone, chatting with William Shatner and Alex Ferguson and the pain of being a Scottish football fan!

8.15am: Morning all, anything interesting happening today?

Thanks for joining us this morning for the most eagerly anticipated annual event in the chemistry calendar – the chemistry Nobel (or chemistry Christmas as it’s become known here). We’ll be bringing you all the news and events in the run up to the announcement of the prize at 11.45 CEST/UTC (10.45 BST) at the earliest and following the awarding of the most prestigious prize in chemistry. We’ll be tweeting from @ChemistryWorld and you can find us on Facebook too. You can also watch the prize announcement made live over on the Nobel Foundation site and we’ll be hosting the video here shortly before the announcement is made. If you’re on Twitter then you’ll want to follow the hashtag #chemnobel and #nobelprize. We hope you’ll stay with us too over the next couple of hours in the run-up to the announcement as we’ll be posting some analysis of the chemistry prize, look at who’s tipped to win and some Nobel trivia. We’ll also be running a special all-things-Nobel-prize-related edition of our regular Re:action newsletter later today, rounding up the best of our stories and the rest of the web. If you’d like to receive it later today then sign-up asap.

No comments yet