Escape rooms, murder mysteries and virtual reality are being used to try to make the subject more attractive to students

Chemistry is a challenging and demanding subject to study at any level. With data suggesting that enthusiasm to study the subject past A-level may be on the decline, the onus is on educators to keep it interesting to a wide variety of learners.

One approach growing in popularity is gamification – incorporating gameplay into teaching approaches to engage and motivate students in their learning.

‘Chemical education requires teaching a lot of skills and learning a lot of sophisticated ways of thinking about complex facts,’ says Craig Butts, head of chemistry at the University of Bristol, UK. ‘Anything that makes that better and more exciting for some or all of our students is a positive thing.’

The possibilities with gamification in education are endless – from simple card games to murder mysteries and escape rooms; the limit is ultimately the imagination of the creator. Through gamification, tutors can help students improve their critical thinking skills, assist their retention of course materials and offer an opportunity for them to enjoy otherwise tedious assignments.

However, as is the case with all games, this approach isn’t every student’s cup of tea, and not all aspects of chemistry can be effectively taught in this way.

Chemistry escape room

Escape rooms, in which people are locked until they manage to solve a series of puzzles or accomplish certain tasks within a set time, have become a hugely popular form of entertainment in recent years, but they can also be a tool for teaching chemistry.

The science and education team of the German Chemical Society’s young chemists network was keen to find a way to get high school students excited about chemistry and encourage them to continue studying it at university.

‘We need more students in chemistry; first semester numbers in Germany – and I think this is true for chemistry studies worldwide – are in strong decline,’ says Monja Schilling, a PhD student at Helmholtz-Institute Ulm for Electrochemical Energy Storage, who leads the project.

‘We wanted to have something which could be played in every school … because many of the published escape games require a lot of resources … and it’s a lot of organisational work for the teachers.’

In ChemEscape, students ‘enter’ a lab and carry out six different experiments that enable them to explore a variety of chemistry areas, from understanding electrochemistry – Schilling’s field – with a lemon battery and learning about fluorescence with riddles on UV-Vis, to carrying out dilution with food dyes and exploring stereochemistry with different aromas.

The premise of the game is ‘you’re hiking with your friends and then you come by an abandoned lab in the woods and you hear a scream,’ Schilling explains. ‘The scientist is lying on the floor, and he says, “I found something super nice. But can you help me to finish the experiments?” And then you need to find a secret code within 60 minutes. If you win, you help the scientist save the experiment.’

Developing and finalising ChemEscape took Schilling and her team around a year, but now schools can access the game for free on their website, in a range of languages.

For schools in Germany, the team also provide boxes containing all of the necessary materials, free of charge; so far they have sent off around 1500 packs and responses to the game have been hugely positive, with around 90% of teachers saying they would recommend it.

‘Teachers have so much to do … they’re already struggling, timewise, with daily life and keeping everything running,’ says Schilling. ‘So if somebody can make resources available, free of cost to make sure that everyone can access them, that’s the best way.’

Solving a chemistry mystery

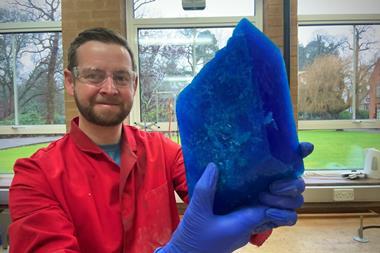

Nicholas Harmer and Alison Hill, both biochemists at the University of Exeter, UK, designed a murder mystery gamification session to help students revise and integrate their learning on one of their second-year undergraduate modules.

Harmer and Hill are avid game-players in their spare time, but the primary motivation to incorporate games into their teaching came after issues surfaced during the Covid-19 pandemic.

‘We had observed in one of our lab write ups that [students] were relying on one piece of data rather than looking at all of the pieces of data and trying to make all of them make sense,’ says Hill.

‘We were determined to try and find a way for them to look at all data collectively … and not ignore something that was inconvenient.’

As well as enhancing students’ holistic understanding of the content, they were also seeking a way to reinvigorate interactions with and between students after an extended period of remote learning.

‘There were a lot of students who we [only] knew as a set of initials because we had never seen their faces,’ says Harmer.

‘So having something that’s interactive, that people would feel inclined to turn up for, that was engaging and enjoyable – there was a need to provide that for students who were, understandably, not having an ideal university experience.’

Harmer and Hill were inspired by two popular murder mystery games, Mafia and Among Us.

‘Essentially the idea is that there’s a murderer going round, and [you have] to try and deduce the murderer based on samples from the murder scenes against samples from suspects,’ explains Harmer.

‘The students get an incomplete dataset, and then they’re given a certain amount of time [before] another piece will come, and then another, and another; there’s enough time that if you understand it well, you can quite quickly work out what’s going on, but for students who are not as experienced looking at these sorts of data, they often need a bit more processing time, which is why we get them to do it in teams.’

After the students have had the opportunity to examine a few pieces of data, Harmer and Hill then bring them together and get them to vote on their top suspects. (Unlike Mafia and Among Us, the students are observers, rather than participants, so there’s no elimination round.) The game is then repeated once or twice more.

‘At the end of the session, we have a final vote on who they think it is, and then we have the big reveal,’ says Harmer.

One of the aims of teaching the content in this way is to reinforce to students the importance of generating replicates in their data and not relying on a single set of results.

‘We’re priming them to think like a real scientist and to design experiments for when they do their projects in their final year,’ says Hill.

Virtual chemistry

Gamification is about using tools to invigorate teaching, and other approaches have embraced advances in technology.

At the University of Bristol, UK, the ChemLabS project has transformed delivery of the practical portion of its chemistry undergraduate course. Through a Dynamic Laboratory Manual, students can access online simulations that allow them to interact with the equipment they will encounter in the lab.

‘What we saw was that the students in the lab were much more confident about what they were doing,’ says Butts. ‘And of course, the lab experience was much better because they had lower stress.’

The next logical step for ChemLabS was to incorporate virtual reality (VR), allowing students to interact directly with objects or molecules – whether that’s putting glassware together or diving inside a protein channel.

With VR gamification, some people love it, and some people think that it’s trite

‘A lot of our VR work is driven through our research activities and trying to use VR as a way of interacting with the data that we get out of it, for example, molecular dynamics calculations of proteins,’ Butts explains.

However, VR is not something everyone finds useful – in fact, for some people it can be discombobulating. ‘We’re dealing with a diversity of people who have a diversity of interest and a diversity of ways of learning,’ says Butts. ‘With VR gamification, some people love it, and some people think that it’s trite.’

Right time and place

This is true for gamification in general. While it can be an effective tool to help reinvigorate teaching, it doesn’t always have a place.

Harmer has since gone on to develop a card-based game for another module of the course to aid understanding of how enzymes work, but he recognises that gamification can be a real turn off for students who don’t like to learn in that way.

‘I have seen people who turn their entire module into a gamified module,’ says Harmer. ‘[But] where it comes into its own is for those students who are currently finding the sit-down [taught] classes really hard work.’

You’ve got to enjoy what you’re doing

Hill agrees: ‘You want something that’s authentic and meaningful, not just, “let’s have a fun session and play a game” – it has to be educational.’

‘If it’s completely overused and not that good from an educational point of view then the students are also not encouraged anymore,’ says Schilling.

‘If you use it on special occasions where the students can understand the benefit … then I think it’s absolutely perfect.’

Whatever approach educators decide to use, Butts feels strongly that everyone should be continually finding ways to keep students engaged.

‘You’ve got to enjoy what you’re doing,’ he says. ‘As a student you go through phases. We get A-level students coming in who are excited about their chemistry, they love it, they want to know everything, and then by the end of their degree, some of them have lost that excitement, because it’s turned more mundane,’ he explains.

‘Gamification is one way to add interest to a programme that might have otherwise lost the interest of some of the students if you didn’t do it – it’s a huge positive.’

No comments yet