Maintaining a healthy chemistry pipeline requires affordable education and training routes

The health of academic chemistry in the UK over the past 20 years has been mixed. While the proportion of A-level students studying chemistry has increased steadily, over the last few years there has been a decline in chemistry undergraduate numbers; and while 2004 fears that only six university chemistry departments would survive to 2014 proved unfounded, a new wave of chemistry department closures is on the cards – with the department at the University of Reading most recently announced as under threat.

To some extent, the fate of university chemistry is tied to wider issues around higher education funding. The Office for Students predicts 72% of universities in England will spend more than their income next year. To make up the deficit, some are cutting courses that are more expensive to teach, like chemistry.

University is becoming unaffordable to an increasing number of prospective students too. Increases to the maximum maintenance loan available have failed to match inflation since 2021. A 2023 survey of undergraduate students at Russell Group universities found one in four of them regularly went without food and other essentials.

At PhD level, the UKRI minimum PhD stipend, also used as a benchmark by other funders, has once again (despite a significant increase in stipend levels in 2022) fallen below the net income of someone working full-time on minimum wage – a gap which will widen further with the planned increase in minimum wage next April.

But university isn’t the only route into a chemistry career. The future of our chemistry workforce depends on making sure that school students know about apprenticeships and other work-based training opportunities when they weigh up their options. Those routes also ensure that people who haven’t been to university are able to progress in their career.

Many jobs are advertised as requiring applicants to hold a degree, but it’s not so much the qualification that matters – it’s the skills you’ve developed during your studies. These are things you can also learn on a job or through alternative training means – and perhaps through those methods, you get skills even more closely aligned to what the job requires.

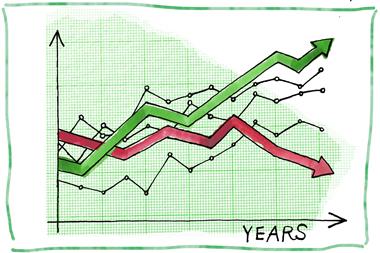

And while salary isn’t everything, more needs to be done to promote the fact that chemistry careers lead to good incomes. Over the past 20 years, salaries in a range of industries where chemists are employed have generally stayed above the UK median salary (although none of them – nor the median either – have managed to stay ahead of inflation). An important part of fostering a diverse and innovative chemistry community is making sure everyone who wants to take part can afford to do so.

No comments yet