The national shame destroying a country’s scientific future

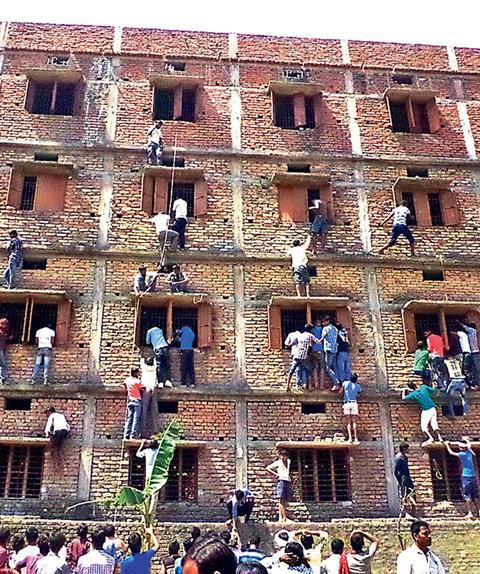

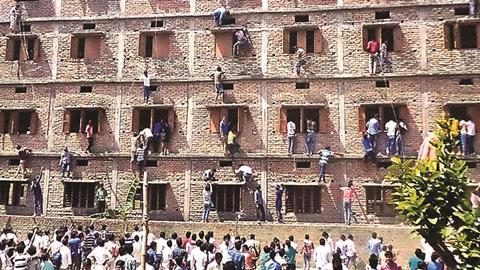

In 2015, photos of parents and friends climbing up high school walls to reach classroom windows in the Indian eastern state of Bihar were splashed across newspapers around the world. The students inside were sitting the crucial 10th standard public board exams (equivalent to the UK’s GCSEs). The climbers were there to help them cheat.

The notoriety of the images rocked India’s education system but was not strong enough to bring about any change. Cheating remains commonplace. In March 2016, in the southern state of Karnataka, exam papers for the chemistry pre-university course (equivalent to the UK’s A-levels) were leaked twice in the span of 10 days. This resulted in several thousand students having to sit the exams three times, sparking huge protests and forcing the government to investigate. Surprisingly, an aide of the medical education minister, among many others, was caught up in the scam – he had been trying to get the questions for his own child.

In the same year, the supposed best students in Bihar were forced to sit a retest when they couldn’t answer even basic questions on their subject during a TV interview. Saurabh Sreshtha, who had the highest grades in science during the state’s 12th standard exams (again, equivalent to an A-level), said aluminium is the most reactive element and was unaware water and H2O are the same thing. Ruby Rai, who had gained the highest grades in humanities, claimed that political science (or, as she called it, ‘prodigal science’) was about cooking. Rai did not turn up for her second exam, claiming she was unwell; Sreshtha failed.

The student with the highest grades in science said aluminium is the most reactive element and was unaware water and H2O are the same thing

Cheating is not limited to school and college examinations. In 2017, a probationary police officer sitting a national level examination for the civil service was caught cheating. His wife and a friend had been feeding him answers using a mobile phone with a Bluetooth device. Strangely, the cheater had already passed the test (he’d been trying to improve his grade), and even ran a coaching centre to help students take the exam.

A social menace

‘Cheating has been endemic in our education system – and it’s turned out to be a social menace,’ says Amman Madan, from Azim Premji University in Bangalore. The more students cheat, the less reliable exams become, meaning that unqualified candidates can end up taking university places, affecting the performance of colleges and universities.

‘As a consequence of this widespread malpractice, we are creating an unequal society and students who clear exams by cheating are unable to integrate or unable to succeed in the new economy that has emerged in the country. These students are not equipped to compete with those who are genuinely knowledgeable,’ Madan says. According to the Unesco Science Report published in 2015, ‘prospective employers have been complaining about the employability of graduates churned out by local universities’.

Part of the problem is the Indian school system, which is complex and governed by different bodies. Broadly, these fall into two groups: schools affiliated to states, or those associated with a central authority (the federal government). ‘Mass copying is more prevalent in some state board examinations compared with central boards,’ observes Madan. Cheating is also more common as one moves away from urban areas. As much as 85% of all schools in India are located in rural areas, making them difficult to monitor.

The techniques the cheaters use take various forms. Mass copying, leaking exam papers, impersonating students and bribing invigilators are common techniques. Technology is also making cheating more sophisticated – Bluetooth phones or headsets are used to receive information, and have even been concealed inside writing pads.

Examination malpractice has become a flourishing business. In some states, students can rig the exam to ensure their answers receive a passing grade for as little as £500 (they need to shell out more if they want good scores), while others pay £100 or more to obtain the questions beforehand or to have someone sit the exam in their place.

There is also a link between state education board officials and mass copying in state board examinations, particularly during the 10th and 12th grade board exams, says Roop Kishor Gupta, from Aligarh in Uttar Pradesh. This is not a new problem, Gupta recalls; in the late 1980s and early 1990s mass-copying was so rampant in Uttar Pradesh state, the then local government came up with a stringent anti-copying act, making exam cheats face prison without bail. ‘This rule brought down the pass rate to around 15%, from around 60% in 1992,’ he says. ‘However, this law was repealed when the government was changed. Not surprisingly, the pass percentage increased significantly.’

The root causes

The students most likely to cheat are the ones who fail to learn. Many education experts in India blame lack of capable teachers, proper infrastructure and good books in schools – particularly in those run by the states. Savita Ladage, of the Homi Bhabha Centre for Science Education in Mumbai, has been associated with Indian Chemistry Olympiad programme for several years. She believes the resources on offer drive people to memorise answers rather than appreciate their context. ‘Text books developed by state boards are poor quality in India,’ Ladage argues. ‘They are one of the most important sources used by both teachers and students … Poor quality textbooks do not help in understanding the subjects and, as an end result, [students have to] focus more on learning by mugging.’ With poor support coming from the state and constant pressure to show improvement in grades, this can also force teachers to help their students pass the exams by any means necessary.

[Aspiration] has created a parallel education system… it has brought a class divide between the haves and have-nots

This affects the vast majority of India’s classrooms. Close to 80% of students are enrolled in government-run schools as they cannot afford private education. And, with 20 million students attending different state and central board exams every year to enter colleges, admission is becoming increasingly competitive. This is particularly true of India’s Institutes of Technology: only 2% of the 500,000 students who sit the entrance exams every year are admitted. With a good job a big aspiration for India’s burgeoning middle classes, students know failure will cost them admission into college and affect their future prospects. ‘It is a complex problem and has created a parallel education system, affecting our education system. It has brought a class divide between the haves and have-nots,’ Ladage says.

This parallel education system, generally only available to economically-privileged students, takes the form of private tuition classes – often focused on coaching students to secure admission to a premier medical or engineering institution. Private coaching in India has turned into a multi-million pound industry on a scale unparalleled anywhere in the world and, with most of these classes maintaining close ties with existing colleges and schools, regular classroom teaching has been seriously affected.

Solving the problem

Dealing with such a widespread issue isn’t easy. There is no common legislation for cheating in India – education is managed by local governments. As such, different states have tried to tackle the problem by initiating different measures. These include setting up CCTV cameras at examination centres, strengthening monitoring squads and instituting stringent laws that include punishment and fines. Rules have even been tightened to define what students can and can’t wear in an attempt to prevent cheaters sneaking in answers. In 2017, during a national entrance test, rules were so strict girls were asked to remove their hair-pins, bands and ornaments; boys were asked to wear short-sleeve shirts so they couldn’t carry in chits or hide answers on their arm. Unfortunately, this went too far: in one incident, a girl was forced to remove her underwear as it had metal buckles.

Currently, India is still searching for answers to its cheating epidemic. ‘Accountability and transparency will help reduce cheating in a big way,’ suggests former civil servant Harish Gowda, who has been a pioneer in bringing transparency in Karnataka State board exams in the late 1990s. For the first time in India, Mr Gowda ensured that photocopies of answer sheets of 12th standard exams were made available to students after valuation, at a nominal fee. The intent was to bring in transparency – and counter several allegations of negligent or biased evaluations.

Gowda argues there are several unconventional ways to tackle this problem of mass cheating, such as introducing random checks of answer sheets. However, while this could be implemented easily, it is only a short-term measure that doesn’t solve the core problem: India’s education system needs to be overhauled. For a long-term solution, Madan suggests that the government needs to dramatically improve condition of government schools, recruit capable teachers and provide them with good salaries. Education also needs to stop being a financial burden on students (and their parents) if they want to succeed.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t look likely to happen soon. The amount of India’s national budget spent on education has stagnated over the past eight years, falling from 3% to 2.9% according to the latest figures. As far back as the 1960s, the Indian government’s Kothari Commission had suggested that education spend should be around 6% of GDP. It looks like India’s two-tier education system, the cheaters and those who profit from the demand to succeed are all here to stay.

No comments yet