The environmental chemist on adapting to different cultures and empowering others

Catherine Ngila is visiting professor at the University of Nairobi, Kenya, whose research focuses on the use of nanotechnology in water treatment. She has served as the executive director of the African Academy of Sciences, and was previously head of the applied chemistry department at the University of Johannesburg. In 2021 she was selected as the L’Oreal–Unesco Women in Science laureate for Africa and the Arab States.

My journey in academia started at a very early age. I had a mathematics teacher in primary school who really grilled us to make sure we did well in maths. That gave me a strong background for science, so in high school I picked physical sciences and then in university I took chemistry and mathematics.

When I was doing my master’s degree, I took a project to investigate the leaching of aluminium from cookware. But it went further to look at aluminium in water supplies in Kenya, that was in the 1980s. I continued with aluminium for my doctorate, and then the water system – issues about water monitoring, and methods of filtration and removal of pollutants – became part and parcel of my interest in research.

I did my doctorate in South Australia. It was my first time to travel out of Kenya and it was quite awesome for me. It was very exciting to go and study in another country. African culture is quite different from Western culture. We also had quite a number of African students at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, as well as in Melbourne and Perth. Australia also has a lot of Chinese and Southeast Asian students – it was a multicultural setting and I was happy to learn a lot about other cultures.

I struggled a bit when I came back to Nairobi from Sydney, because I didn’t have the equipment I wanted to utilise, we didn’t have the research funding, the infrastructure and all that. Eventually I made the decision to move to Botswana. I was there for nine years and then I moved to South Africa for various reasons – one was family, and a second was that the economy was bigger and there was more research funding and opportunities. That was when I really grew as an academic.

I want to be able to understand the person I see today

I’ve been very lucky over my career – but it was just that I got opportunities. And so I think it is good to give other people opportunities. I set up a foundation called the African Foundation for Women and Youth in Education, Science, Technology and Innovation. The focus is to transform women and youth – in their research, in education – encouraging that through mentorship. When I receive requests from young researchers, I say ‘Ok, no problem – what kind of mentorship do you want – is it in research? Help with writing proposals? Is it just in life generally – about the path that you want to take?’ So it’s a whole range of mentorship.

My advice to PhD students is to ensure that, whatever research you are doing, you publish. Networks are also very important. When you network with other people, you learn a lot. Try as much as possible to visit other labs to see what everybody else is doing. For those who are disadvantaged, who are at universities that do not have a lot of facilities, the best thing they can do is to reach out to other established researchers.

I am very passionate about empowering my students. They’re under your tutelage, but after some time they will be independent – so you must start teaching them how to be independent. For every single student in my lab, I always make sure to get funding to sponsor that student to attend an international conference to give them exposure. And I’ll also give them opportunities to write funding proposals. Towards the end of their doctorates, when they want to use the findings from the research to write papers, I’ll encourage them to be the corresponding author. And always my students, whether master’s or PhD, will be the first author – because I respect that fact that they are the ones who are doing most of the work. My job is just to mentor and give direction.

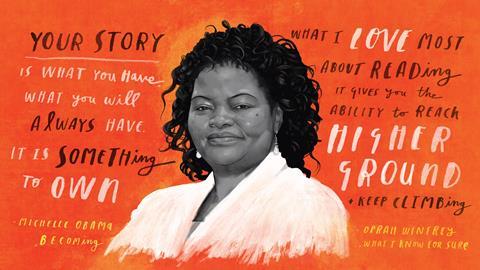

I have a soft spot for reading famous people’s biographies. I want to know how [Barack] Obama became Obama. Oprah Winfrey, Michelle Obama, [Donald] Trump, King Charles – I like to know what kind of life they lead. I want to be able to understand the person I see today. That person was a young person initially, and so the path, the journey they walked is very, very important.

Governments in developing countries have to recognise academia and research as one avenue of national development. Do they see the opportunities in research, particularly empowering researchers, and also equipping infrastructure for the research to flourish? Because that research is going to inform so many things – it’s going to inform water issues, it’s going to inform malaria treatment, it’s going to inform vaccine generation. But it’s one thing to have a national development plan with a research agenda on paper – you have to actually implement it.

No comments yet