A teaching technician in England is helping to make her labs safe for the start of term in September

During this difficult time, Chemistry World is checking in with notable chemists around the globe to see how they are weathering the coronavirus pandemic.

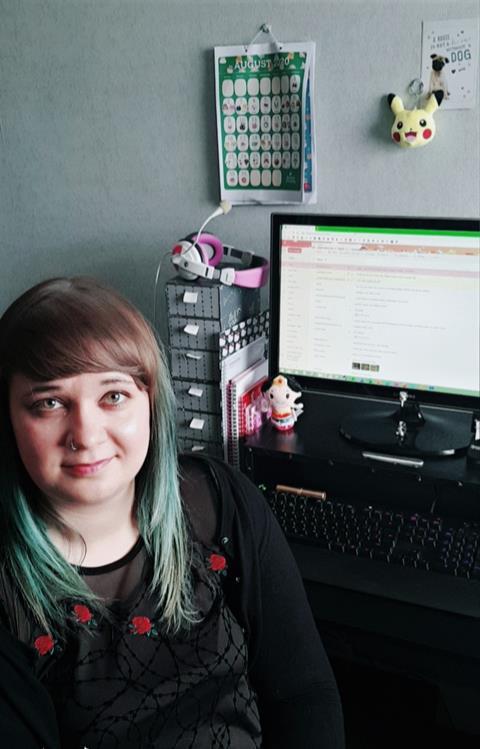

Hannah Beska, a teaching technician in the chemistry and forensics department at Nottingham Trent University in England, is part of a team working on plans to reopen the school’s teaching labs safely when the autumn term starts in September.

‘We will have a smaller number of students in the lab, instead of around 40 we will only have about 20,’ says Beska. She notes that a few of the lab sections will still be held in-person, while the rest of them will be a blend of hands-on and virtual.

‘Some of our technical staff are on a rotation and are doing full cleanings of the labs, putting markings on the floor to facilitate physical distancing, and identifying any problems with our current risk assessments before we are back in session,’ Beska adds.

The university essentially shut down in mid-March when Covid-19 hit – classes went online and Beska and colleagues were sent home to telework. Access to labs was reserved for essential activities like maintaining instrumentation, research animals and cell lines, but technical staff returned to campus on a rotating basis on 11 August to prepare for the new academic year. Only ‘a fraction of the staff are in at any point, to help with social distancing,’ Beska says. When in different locations, they use Microsoft Teams, email and telephones to communicate.

Currently, research groups must apply to the university to regain access to the labs, explaining why their return is necessary. A risk assessment is also required, as well as a list of measures put in place to minimise Covid-19 transmission. The university’s safety team reviews such lab access requests, and if approved the researchers involved must work with security to regain access to the building.

Halving chemistry students in the lab

While masks will not be required in the labs, a distance of at least 2 metres between students will be enforced, including at fume hoods. Only one student will be able to work in a fume hood at a time, when previously there were two.

Normally the two chemistry bays hold roughly 40 students, but in the new term only about 20 will be allowed. As the technical staff will be on a rota, there will only be two from the chemistry team on duty during any given week, when there were four pre-pandemic. The lab, which is a shared space between the chemistry, microbiology and biochemistry teams, has a maximum capacity of 200 people.

The typical personal protective equipment (PPE) – safety glasses, lab coats and gloves – will also be mandatory. Only first aiders will wear different PPE, including face visors, since they must come in direct contact with people if first aid is needed.

There are also stations with hand sanitisers and disinfectant wipes at every entrance and exit, as well as requirements for regular handwashing and cleaning of workspaces.

After the labs closed on 17 March, Beska worked from home until the very end of April when she popped in to do essential maintenance. Afterwards, she continued to go back fortnightly for several months. It is only since 11 August that Beska and other technical staff are back on campus on an alternating schedule every other week.

Technical training

Beska has travelled a unique road. She does not have an undergraduate degree, but instead did an apprenticeship at the University of Nottingham and in 2015 earned a higher national certificate, which is a one-year course equivalent to the first year of university. She worked there until 2018 as an analytical lab technician and specialist on ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy and atomic absorption spectroscopy, and has since been working at Nottingham Trent.

She lives in Nottingham with her partner, who works at a hospital and was required to report there each weekday throughout lockdown. During the home self-quarantine period, she found herself alone a lot with their dog. ‘I would be doing my paperwork, emails and phone calls with other technicians at home and … it felt a little bit lonely,’ Beska recalls.

It proved important to get out of the house regularly, so she took her dog for lots of walks by the River Trent, and in new places like nature reserves. They also foraged for elderflowers and cherries to use in cooking.

One positive thing to come out of the pandemic, according to Beska, is a significantly expanded and enhanced online learning environment. ‘There is so much available that wasn’t previously,’ she says. ‘Before, I struggled to get supplemental training, and usually I had to go to a conference somewhere.’

Such a virtual community allows for live interactions like question and answer sessions with the presenter, Beska notes. ‘This greatly broadens access to information, and it can help us inspire future generations of scientists,’ she says. ‘I am excited to see what other new ways we come up with to do business.’

Chemists amid coronavirus

How chemists around the world are coping with life and work during the Covid-19 pandemic

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Chemists amid coronavirus: Hannah Beska

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

No comments yet