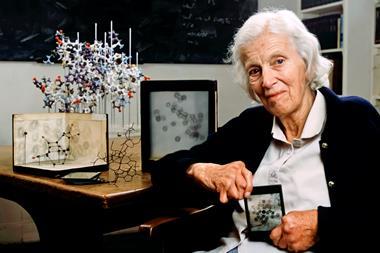

The drug delivery expert and multidisciplinary researcher on the importance of learning from failure and how a summer in a margarine factory influenced her career

Yvonne Perrie is the chair in drug delivery at the University of Strathclyde’s Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences in Glasgow, UK. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry, Perrie was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 2024 New Year Honours list for services to pharmaceutical innovation and regulation.

I wanted to become a fighter pilot, but in the late 1980s women were not allowed to fly planes. That was the first time I learned that my gender impacted my career. I’d never seen it before. I grew up in a world where I thought I was surrounded by female role models, and it never occurred to me that there would be a job I couldn’t do as a woman. It was a reality check.

I wanted a clear route to a career; pharmacy offered all the sciences that I enjoyed and a clear application so it was very easy for me to then see my career path and that excited me.

During my time at university, I worked in a margarine factory – it was awesome. I really got excited about manufacturing and that took me to focus more on the process of making medicines and formulating them better for the patient.

I worked for a year in a community pharmacy. Getting to know the patients was always fun, but by that point I’d already applied to do a PhD so I then moved to London to do my PhD but also worked as a pharmacist at weekends.

The best day of any year in academia is graduation. Seeing people graduating and then going on and having their career – I’m very proud of playing a small part in that.

When products don’t make patients’ life better, it’s always sad. In the late 1990s/early 2000s it was clear that gene therapies weren’t working with the non-viral systems that we were working on. They worked in mice [but] then with the scale up to human, the dose was impossible. That was a low point for funding and a low point for enthusiasm. Being able to recraft what I did to apply it to different topics, but keep my existing skill set, was difficult.

I’ve always been very focused on the journey from bench to bedside, and a big part of that is the cost – if you can make things cheaper and more effective then they’re more globally accessible. The biggest challenge we still face is making sure we can make high quality medicines at a low cost, that are also reproducible and safe.

In my lab it’s all about teamwork – joint papers, joint research, sharing the load, sharing the fun, sharing the pain. When the experiments don’t work, it’s good to have somebody to talk to – the best things are always shared.

Short-term contracts for postdocs hurt us all. We lose a lot of high-quality science because people don’t want to stay on that treadmill. That is a challenge that we need to look at. How do we keep people on a career path where they feel stable and secure?

Better support to help families share the maternity leave on childcare is important, there’s been a lot of work done on that and universities are generally very supportive, but we’ve got a journey to continue to improve that.

You can’t take yourself too seriously

I’m always in awe of people who have much more detailed knowledge than I have. Multidisciplinary teams are a really good way to go, but we need to make sure enough of us can actually join the dots together to make the team work.

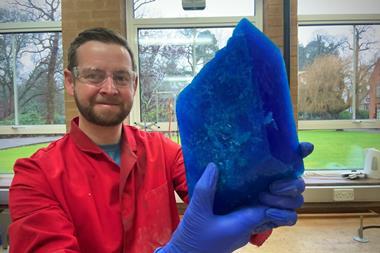

I want to bring down the cost of goods for liquid nanoparticles – they’re expensive. We focus a lot on how we can manufacture them more cheaply and make them more effective. Making them cheaper and easier to ship will improve global access which will help everybody.

I’m not a fan of multitasking, it just creates chaos for me. I try and time block my day as much as I can.

I don’t enjoy working from home. I feed off the energy in the university – if you feel like you’re struggling, you can just walk out, make a cup of tea, talk to somebody and say, ‘I don’t know how to do this’. They might give you an idea or, worst-case scenario, they give you sympathy.

Good research culture is about being able to learn and fail without judgment. We’re allowed ‘soft fails’, as I would call them – you can learn from them, but you don’t jeopardise your health and safety.

Everybody should try a range of options for a career – in both academia and industry. Explore and see what works for you and your life, what you’re doing, where you want to live, who you want to be. Everybody can make a great career no matter what they do, and they should do it in a situation that makes them happy.

I love to try and fail at learning to play instruments. On X, I describe myself as an ‘aspiring grade one violinist’. I did start violin lessons, and then my violin teacher quit on me! It’s quite grounding, I like to try different things and I don’t care if I don’t do them well; what I lack in talent, I make up for an enthusiasm – you can’t take yourself too seriously.

No comments yet