Chemistry departments are closing, while multidisciplinary centres are opening. The implications of this for chemistry are being hotly debated. Bea Perks explores the issues

Chemistry departments are closing, while multidisciplinary centres are opening. The implications of this for chemistry are being hotly debated. Bea Perks explores the issues

Are the days of the chemistry department numbered? A growing number of chemists in UK universities no longer work in chemistry departments. Recent department closures have incited protest from the highest authorities, but there were some who saw such an evolution as entirely natural. The global move towards cross boundary integration and multidisciplinarity can’t be ignored, but what that means for the future of the chemistry department remains hotly debated.

The closure of university chemistry departments across the UK has hit the headlines. Perhaps the most highly publicised announcement was the University of Exeter’s in December 2004 (see Chemistry World, January 2005, p9).

The University of Exeter said it was responding to market forces when it announced the closure of its chemistry department. The department had scored a UK research assessment exercise (RAE) rating of 4, short of the top 5 or 5* spot - ie ’nationally excellent’ rather than ’internationally excellent’ - making it less well funded than departments at, for example, Imperial College London or the University of Cambridge. That, together with the expense of teaching chemistry, rendered the department, in the eyes of the university, unsustainable.

Government to blame?

Arguments were ignited, and continue to spark, over where the responsibility for such closures lies. Over 15 chemistry departments in UK universities have closed in the past 10 years, according to the RSC.

Most organisations and individuals put the blame firmly on the government, but for different reasons. The House of Commons science and technology committee recommended that a regional presence for strategic subjects, such as chemistry, should be set up to aid local industry and allow students to study near to where they live.

The committee concluded, as does the RSC, that regional provision is key. The RSC has warned of ’regional deserts’ in chemical science provision appearing where neighbouring university departments close. Increasingly impoverished students will want to study nearer to home, goes the argument, and industry uses local universities to develop specific skills or to do specialised research.

Universities UK, an organisation that represents the country’s vice chancellors, also holds the government responsible for department closures, but it disagrees with the conclusions of the select committee and the RSC.

’We are strongly opposed to top-down centralised planning of provision, whether imposed by the funding council or other government agency,’ the then president of Universities UK, Ivor Crewe, told a meeting at the Institute of Physics last year. Universities UK also suggested that companies would look for academic collaborators that most closely matched their needs, rather than collaborators that most closely matched their location.

Certainly the regional provision argument didn’t go down well with some staff at the newly renamed Anglia Ruskin University (formerly Anglia Polytechnic University). The university announced the closure of its chemistry department in December 2004. Chemistry has been moved into the forensic science department. The loss was not great for the region, pointed out staff at Anglia Ruskin, because the university is in the same town as the University of Cambridge.

Another institute that objected to some of the accusations it faced when it closed its chemistry department was the University of Dundee. Dundee closed its division of physical and inorganic chemistry in August 2005, having transferred its chemistry department into its life sciences faculty when it formed in October 2000. The university replaced the chemistry degree it offered - which attracted only four students in its last year - with a degree in pharmaceutical chemistry that immediately attracted 14 students and is tipped to attract between 20 and 25 once it has become fully established.

So rather than killing off a subject, as press releases from external organisations suggested at the time, the university has seen a remarkable surge in uptake onto its chemistry course, says Mike Ferguson, co-director of the university’s post-genomics and molecular interactions centre. With such a low uptake to the original chemistry courses on offer, Ferguson says he was keen to avoid running the department into the ground as he had seen happen at Exeter.

Interdisciplinarity rules

The chemists that moved across from Dundee’s chemistry department to the life sciences faculty now work in the division of biological chemistry and molecular microbiology, which is housed in the university’s Wellcome Trust Biocentre. This facility forms part of a research complex that includes the university’s new Centre for interdisciplinary research, which opened in 2005 (see Chemistry World, January 2005, p8).

In addition to the Dundee chemists who moved across the campus, a number of leading researchers have been recruited from other universities. The benefits of cross-disciplinary interaction become clear from talking to the chemists. ’There’s a buzz,’ says Ian Gilbert, professor of medicinal chemistry who came to Dundee following a professorship at Cardiff University. ’It’s alive with ideas.’

Dundee is particularly known for its work on neglected diseases, notably African sleeping sickness, Chagas’ disease, leishmaniasis and malaria. Gilbert is looking at the design and synthesis of potential drugs for these mass killers.

The strength of the interdisciplinary approach being taken at Dundee, and being seen increasingly in universities worldwide, is that the whole drug-discovery process, from target identification to drug, can be worked on under one roof: synthetic chemists talking to biochemists talking to molecular biologists and so on.

This leaves some people questioning the existence of chemistry departments at all. The Higher Education Funding Council for England (Hefce) certainly hasn’t said that, but Hefce members have said that the market forces behind closures like that at Exeter are inevitable and natural. Hefce chief Howard Newby has reportedly complained that many subjects are still defined by 19th century disciplinary categories, when so much cutting-edge research crosses subject boundaries.

’Hefce should guard against an overly interventionist role in the market,’ agreed board members who examined the issue of whether there are any higher education subjects that are of national strategic importance where intervention might be appropriate to keep them going. ’The council should be wary of preventing the natural development of disciplines or infringing institutional autonomy or academic freedom.’

More chemists, fewer departments

Newby notes that the number of chemistry staff in England is increasing even though the number of departments is decreasing - because chemists are not restricted to chemistry departments.

It was a point echoed by Willie Rennie, RSC Scottish parliamentary affairs consultant, on a tour of the labs in Dundee. ’Someone will have to come up with a very complicated formula to figure out how much chemistry research is being carried out in universities that do not have chemistry departments per se,’ he said.

New labs like this hint at a bright future for chemistry in UK universities |

Dundee marks a growing move towards cross-boundary integration at UK universities. There are numerous other examples, such as the University of Manchester’s interdisciplinary biocentre (MIB).

The MIB differs from the Dundee set up in a number of ways. For a start, there is also a chemistry department at Manchester. ’The concept is that there’ll be people that belong to chemistry, biology, physics, and informatics; they’ll belong to parent schools but actually do their research in this multidisciplinary research centre,’ says Nick Turner, professor of chemical biology, who came to the MIB last year from a position as professor of biological chemistry at the University of Edinburgh.

Turner moved to Manchester with his wife Sabine Flitsch, who was professor of protein chemistry at Edinburgh and is now working with him to lead research at the MIB’s Centre of excellence in biocatalysis, biotransformations and biomanufacture (CoEBio3; see Chemistry World, July 2004, p11).

Turner and Flitsch chose to move to Manchester because their research is at the life science/physical science interface. ’Chemistry, and certainly the area I’m in, is just moving closer and closer to the biological sciences and informatics,’ says Turner. ’I wouldn’t normally collaborate with what you might call traditional chemists. Most of my collaborators are in other departments, so why not work in the same building as them? I suspect you may see other places like MIB going up over the next few years.’

The heavenly pastures of such blurred boundaries are, inevitably, not quite heaven for all. Some traditional chemists at Dundee fear that their input might be treated as something of a service by their life-science peers.

Collaboration is great, whispered one, but we’d rather collaborate from a more ’equitable’ point of view. On top of that is a fear that, with emphasis on more obviously lucrative - particularly drug-discovery related - research, chemists might face a challenge getting more lab space even if they are successful in winning extra funding.

Long live the chemistry department

But cross-disciplinary centres aren’t about to put an end to all chemistry departments, a point made abundantly clear by Paul O’Brien, head of the school of chemistry at the University of Manchester.

’I strongly hold the opinion that you cannot do interdisciplinary work unless you are a master of one discipline,’ says O’Brien. ’Otherwise it is not clear what skills you bring to a project.’ Disciplines like chemistry and physics and the various types of engineering provide firm frameworks of knowledge that are widely and professionally recognised, he said.

Manchester is heavily committed to interdisciplinary work overall and has established a number of groupings along the lines of the MIB, including the Dalton institute for nuclear science and engineering, and the photon science institute, all of which interact heavily with chemistry.

The MIB is quite separate from the school of chemistry that O’Brien heads. At Manchester, the schools differ from the interdisciplinary centres in that schools or departments are responsible for all undergraduate degree programmes and are also the route for line management and career development for academic staff.

Departments must evolve

The future of the chemistry department is a complex subject, says O’Brien (see Chemistry World, October 2005, p28). There is no simple answer, but regional activities are likely to play a role, he predicts. ’We are all watching the EastChem and WestChem initiatives with great interest,’ he said.

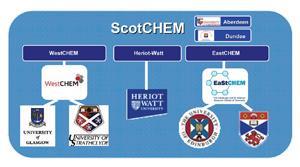

EastChem and WestChem make up ScotChem, a collaboration to pool resources for chemistry research in Scotland. EastChem brings together the universities of Edinburgh, St Andrews and Heriot-Watt, while WestChem comprises Glasgow and Strathclyde.

ScotChem pools resources for chemistry research in Scotland © ScotChem |

The ScotChem programme was awarded ?9 million in September 2005 by the Scottish Higher Education Funding Council (now part of the Scottish Funding Council, SFC) as a one-off investment for four years, along with ?4.6 million from the Office of Science and Technology, and ?9.7 million from the five universities. ScotChem partners will allow unrestricted access to each other’s research facilities and major pieces of equipment, as well as access to any specialist technical expertise for operating these facilities that exists in the different institutions. The universities of Aberdeen and Dundee neither receive nor provide funds but, as participating partners, will also benefit from ScotChem’s unrestricted access to the research facilities at each institution.

Challenging the status quo

A shake up is needed to the way chemistry departments are run, urges Graham Hills, professor emeritus of chemistry at the University of Strathclyde, where he was principal and vice chancellor from 1980-90. There are too many ’patched-up versions of the status quo’ being offered in answer to the question over the future of the chemistry department.

’The current arrangements are not just inefficient, they are fundamentally flawed and therefore doomed,’ he wrote in a letter to Chemistry World (see December 2005, p26).

His views are uncompromising and not what everyone would expect from a professor of chemistry. ’While chemistry remains a vital strand of the scientific knowledge base it is not mainstream and, except in British secondary schools, never was,’ he says. Chemistry has ended up on the periphery of what everyone needs to know having become ever more specialised and increasingly difficult, he contends.

Hills believes that market forces will determine how many chemistry departments are needed, and is clear on how many chemistry departments ’of the existing kind’ are needed: ’The answer is self-evidently none’.

Nobody questions the vital role of chemistry in our scientific base. The questions rest instead on how it should be put into action. And while this article takes only the briefest snapshot of a plethora of often opposing views across the UK, it is clear that chemistry departments can’t afford to stand still. All eyes are now fixed on the evolution of chemistry departments across the UK, and their equivalents around the world.

No comments yet