The development of the British Association of Crystal Growth maps changes in the industry over the past 40 years. Hayley Birch caught up with members at this year's conference

The development of the British Association of Crystal Growth maps changes in the industry over the past 40 years. Hayley Birch caught up with members at this year’s conference

Most people know that 2009 marks 40 years since Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon. Fewer, however, will be aware of another ’ruby’ anniversary being celebrated this year - that of the British Association of Crystal Growth (BACG). As a discipline that has its roots, appropriately for this particular anniversary, in the production of rubies and sapphires for bearings in watches, crystal growth and the BACG’s annual conference now attract an eclectic mix of experts from right across the scientific spectrum.

From its nucleation - if you’ll pardon the pun - in the late 1960s, as an informal group of British crystal scientists, the BACG has grown into a multidisciplinary organisation with considerable reach. At last count, the 2009 conference drew 166 delegates, some from as far afield as Singapore and California, with expertise ranging from the fundamentals of crystal growth to pharmaceuticals and the burgeoning field of nanotechnology. So how did it all begin?

Bar beginnings

Like many good ideas, the BACG was born out of nights in the pub. Past president Don Hurle has fond memories of researchers from Plessey, an electronics company eventually bought by Siemens and GEC, and the Royal Radar Establishment in Malvern, Worcestershire, propping up the bar. ’It was a very informal set of buddies, because these people worked together outside of the meetings. Everybody knew everybody, so the beer drinking...’ he tails off. ’It wasn’t terribly formally academic, which was unusual for the day. It’s got more respectable over the years.’

As Hurle explains, the association was originally focused on crystal growth research for the semiconductor industry. By the 1960s, transistors were taking off and growing perfect crystals of semiconductor materials was becoming increasingly important for manufacturing microchips. Funding during the Cold War also came from the government, which was interested in military applications of semiconducting materials, such as thermal imaging (indium antimonide) and range finders (solid state lasers made from doped crystals).

Spurred on by several international crystal growth meetings and the formation of the American Association for Crystal Growth in the late 1960s, British crystal growth scientists resolved to start their own organisation. And so it was that in the June of 1969, Imperial College London hosted the foundation meeting of the BACG. The late Sir Charles Frank, by then a fellow of the Royal Society and well known to the community for his work on imperfections in crystals, sat on the committee. Hurle recalls Frank, who later became the association’s first president, poring over micrographs at the ’beer and blackboard’ sessions of the early meetings - a skill he says he honed while interpreting reconnaissance photographs during the war. ’I well remember him puffing away on his pipe. Frank could see things that weren’t there,’ says Hurle.

By 1975, the association had a newsletter, a logo - the snowflake crystal design that the BACG still uses today - and the beer had been replaced by something a little stronger; the annual conference programme that year included a lecture on ’vapour transport’, which transpired to be a cunning way of incorporating a whisky tasting session into the event. As former chairman Kevin Roberts, a chemical engineer at the University of Leeds, points out, alongside the serious talks there has always been a lively social side to the association, and plenty of banter - but this, he says, only serves to improve the science.

Growing in a different direction

During the 1980s, electronic materials continued to be a major area of activity for crystal growth scientists - and the BACG continued to be made up largely of physicists. But when the Cold War finally ended, much of the UK semiconductor industry began to fall away and so did the BACG’s membership.

’When I was first a member, sometime in the eighties, it was still very much a semiconductor organisation, with other elements coming along as well but not really being noticed,’ recalls treasurer Tim Joyce, a crystal growth researcher at the University of Liverpool. ’And then there was this big step change - suddenly the semiconductor community not quite disappeared, but faded away. The semiconductor industry has now virtually disappeared in the UK and university people tend to be more specialised, so they go to specialist conferences, not the BACG conference.’

However, interest was by now increasing in organic materials, and particularly in applications of crystal growth research for the pharmaceutical industry. As Joyce notes, there is now a healthy contingent from the pharmaceutical industry at the annual meetings. But when the annual conference in 1993 was attended by just 23 members, it was up to Hurle, at the helm as chairman at the time, to find a new direction for the BACG. As interest in crystal research was becoming broader, the solution was for the group to become more interdisciplinary - which remains an important aspect of the meetings to this day.

Reflecting the decision to widen the scope of the association, and the increasing importance of crystal growth across a variety of different industries, the title of the BACG’s annual conference in 1994 was ’Crystallisation and crystal growth: an interdisciplinary perspective’. Over the next few years, four well-defined activity groups - semiconductor materials, oxide materials, optical materials and chemical/biological materials - emerged, and were developed, to try to broaden the appeal of the BACG’s meetings to organisations with parallel interests.

Sign of the times

The association’s membership has remained healthy, for the most part, since then. And according to Mike Quayle, a committee member and crystallisation specialist at AstraZeneca - this year’s conference sponsor - the 2009 conference has enjoyed the biggest attendance the BACG has seen in a long time. It is certainly a sign of the times that sponsorship for meetings now comes from the pharmaceutical sector.

’In my area, in engineering, there’s huge interest from the drug companies in molecular-based understanding of particle formation for making drug materials and doing that in a very efficient way,’ says Roberts. ’Especially if you can do it quicker, smarter, use fewer people and, low and behold, bring the cost of pharmaceuticals down. If we can hit the science of organic materials in the same way we hit the semiconductor to make microelectronics, then drug costs will come down.’

One thing that hasn’t changed though, is that ties with industry remain important and 40 per cent of those attending the conference are industrialists. The programme itself also retains the same balance of social events and serious lectures, with one speaker complaining of losing his programme in the bar on the first night (whisky tasting also made a welcome return to the programme in 2002).

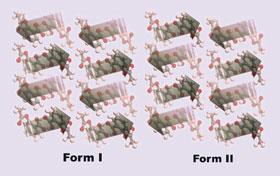

Meanwhile, the association continues to provide a platform for young scientists, both as speakers and by rewarding academic excellence. This year’s winner of the BACG Young Scientist Award is Andrew Bond of the University of Southern Denmark for his work on the crystal structures of aspirin. Often regarded as an interesting example of a compound that shows no polymorphism, Bond’s work proves that aspirin does in fact have more than one crystal form. He says it highlights the fact that crystallisation and polymorphism of molecular materials is still far from predictable, even for apparently simple drug molecules such as aspirin.

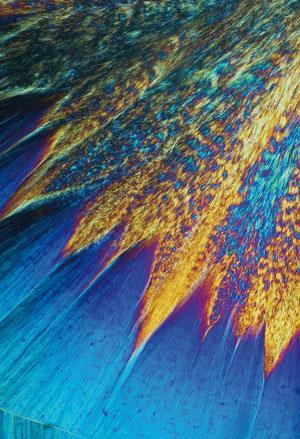

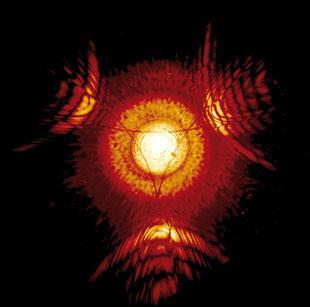

The broadened focus of the organisation and the field of crystal growth in general is evident in the scope of the lectures at the 2009 conference, which, within one session on nucleation, cover topics as widely dispersed as nuclear fusion, anti-malarial drugs and nanoparticle synthesis. As Joyce says: ’It’s a broad church, because a lot of the fundamentals are very similar, but the growing techniques are different - growing from solutions, growing from melts, growing in vapour phase, growing from beams. All seem very different, but in fact nucleation is nucleation however you get there.’

Upon rising to give his lecture on crystallisation theory, Alex Chernov of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the US, jokes that it is ’nice to be a fossil’. But while older members of the group may pine for more discussion of the fundamentals of crystal growth - subjects that occupied more of the association’s members in days gone past - most accept, grudgingly, that change is a good thing. ’[The BACG’s] base has broadened so wide now and it’s dominated by the industrial crystallisation and pharmacology,’ says Hurle. ’Chemistry is to the fore, whereas it was physics, semiconductor physics, that drove it at the beginning.’

Hayley Birch is a freelance science writer based in Bristol, UK

No comments yet