PFASs were used in household and industrial products for decades before their harmful health effects and biopersistence came to light. Rebecca Trager investigates a messy situation

Highly fluorinated chemicals known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) were invented in the US decades ago, and the country is ground zero for the ongoing battle to address the global contamination crisis these compounds have caused.

During the opening session of the April 2019 American Chemical Society meeting, a preeminent chemist stood before a packed auditorium in Orlando and took the entire chemistry enterprise to task for allowing the pollution of the world’s water resources with these chemicals. He echoed the calls of many scientists, politicians and environmental advocates for greater regulation of PFASs from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other regulatory authorities around the world.

‘It is not lost on me that I am a chemist speaking at an ACS meeting, and this is a problem where our industry, our regulators and the entire chemistry enterprise could have behaved better,’ said William Dichtel, an organic chemist at Northwestern University in Illinois. ‘We have polluted the world with this stuff,’ said Dichtel, who has helped develop porous polymers that have water purification applications.

It is almost criminal

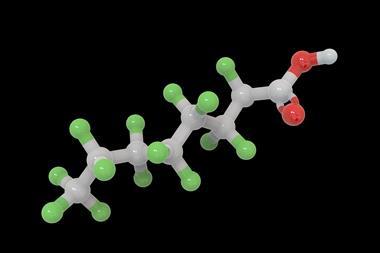

Dichtel noted that the two most well-known and best-studied of these compounds are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) – both of which are known to have damaging health effects and were phased out years ago, yet still persist in the environment. But he warned that these two are ‘just the tip of the iceberg’.

‘As the world caught on to the fact that PFOA and PFOS are toxic, we did not regulate these compounds as a class,’ Dichtel said. ‘We replaced these eight-carbon surfactants with nine-carbon surfactants of almost the same structure – it is almost criminal.’ In fact, there has been successful legal action against companies that manufacture, use, or sell PFASs or PFAS-containing products (see Facing the music section below).

Some of the strongest bonds

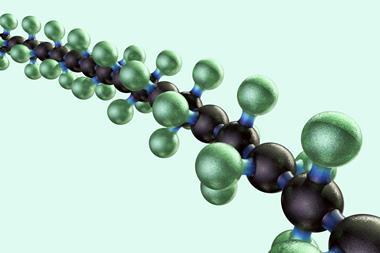

PFAS is the term for a family of highly-fluorinated chemicals that have been used and manufactured since the 1940s in various industries around the world. It’s hard to define them because they have different modes of action and means of transport, but they all have a fluorinated carbon backbone.

These synthetic compounds are designed to be resilient and can withstand extremely harsh environmental conditions. Because they contain carbon–fluorine bonds, which are among the strongest bonds found in nature, PFASs resist breakdown by the typical forces of degradation like sunlight, enzymes in organisms and bacteria in the environment.

The unique physiochemical properties of PFASs impart characteristics like repellency to oil, grease and water, as well temperature resistance and friction reduction. They can therefore help make non-stick products that repel many substances and resist stains. For these reasons, PFASs have been used for decades in clothing, furniture coatings, cookware, food packaging, and many other common household items.

Perhaps most importantly, PFAS chemicals are extremely effective in extinguishing hydrocarbon-fuelled fires so they have been a key ingredient in firefighting foams used on military bases and airports for more than 50 years.

Approximately 5000 of these synthetic compounds have been created and used in commercial products, and roughly 500–600 are estimated to be in active use. The scientific community, however, has good knowledge about only a few of them. The two that have been most thoroughly researched and are best understood are those that have been around the longest – PFOA, and PFOS – and what we know is quite worrisome.

Bioaccumulate and biomagnify

DuPont, and then its spinoff Chemours, used PFOA for decades to produce its popular Teflon non-stick cookware, and PFOS was the key ingredient in 3M’s hallmark fabric protector Scotchgard, as well as firefighting foams and food packaging. They are both considered long-chain PFASs because they contain eight or more carbon atoms.

It turns out that the very qualities that make these PFASs so useful also make them problematic for the environment and human health. They are mobile, persistent and can leach into soil and groundwater to contaminate drinking water. Even consuming small amounts can lead to high concentrations in the body over time.

Not only can PFASs be transported long distances in the environment, they can also accumulate in the bodies of animals, especially those that consume fish. In this way, these substances bioaccumulate and biomagnify up the food chain, increasing significantly in the blood and organs of those at the top. PFOS and PFOA are also found in urine, breast milk and in umbilical cord blood.

These two compounds have estimated half-lives in humans of two to nine years, respectively. The half-life of PFOA in the environment is reported as greater than 90 years, and the figure for PFOS is more than 40 years.

Beyond being mobile and bioaccumulative, PFAS compounds have also been shown to be toxic, though those dangers only became well known in the early 2000s. Research has linked PFOA and PFOS to health problems like liver damage, thyroid disease, reduced immune function, various cancers, high cholesterol, birth defects and fertility issues.

These chemicals are increasingly turning up in water supplies throughout the US. The non-profit Environmental Working Group (EWG) and researchers at Northeastern University in Massachusetts identified at least 712 PFAS contamination sites in 49 US states, as of July 2019. That’s a big jump from their calculation a year earlier of 172 PFAS contamination sites in 40 US states.

Approximately 19 million people are served by public water systems that have reported PFAS contamination to the EPA, according to the EWG. After reviewing federal and state data, the organisation estimated that more than 1500 drinking water systems serving up to 110 million people in the country may be affected.

Military bases are of particular concern because of their extensive past use of PFASs in firefighting foams for training. Indeed, worrying levels of PFASs have been reported by military communities around the country, and the EWG identified 106 military sites in the US with drinking water or groundwater that have PFAS contamination levels that surpass the EPA’s health guideline.

Public health concern

In response to mounting public health concerns, in 2016 the EPA set a lifetime health advisory for drinking water of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for individual and combined concentration of PFOA and PFOS. However, this is non-regulatory and an unenforceable public health guidance.

In its much-anticipated action plan to address the PFAS problem, released in February 2019, the EPA agreed to pursue several steps, including developing enforceable national drinking water quality standards, known as a maximum contaminant level (MCL), for PFOA and PFOS. Establishing such a federal benchmark would trigger mandatory clean-up efforts of affected areas, and ensure that PFAS levels in water systems are at or below a specified safe threshold.

But the EPA’s strategy received a lukewarm response from the scientific community, with many disappointed that it lacked firm commitments and deadlines for action. ‘Awaiting further information means delayed action and more adverse health effects,’ says Harvard University environmental health professor Philippe Grandjean. ‘There are important public health issues at stake and we do not have the luxury of time to gather even more convincing information before deciding on appropriate action.’

Without federal action, individual US states have taken matters into their own hands. Eight have adopted their own regulatory standards for PFAS contamination, and more than 19 are pursuing such action.

New Jersey is leading the way. It was the first state to adopt an MCL and ground water quality standards for any PFAS compound, and in April 2019 it proposed drinking water standards of 14 ppt for PFOA and 13 ppt for PFOS. Last year, the state set a standard of 13 ppt for perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) – a less well-known PFAS that research suggests might be toxic.

Other states are joining New Jersey. Vermont has adopted a preliminary legal limit of 20 ppt for any combination of five PFAS chemicals in drinking water, including PFOA, PFOS and PFNA, and has proposed these limits be codified in a state MCL.

Regulatory action

The growing patchwork of PFAS regulation and enforcement across the US is not surprising, considering the current scientific uncertainties and inconsistent information. In May 2018, for example, news broke that the White House had worked with the EPA to suppress a study by another US government agency that indicated the ‘minimal risk level’ for exposure to PFOA and PFOS should be seven to 10 times lower than the EPA advises. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention finally released that long-awaited draft report in June 2018.

Companies rushed to replace long-chain PFASs with new short-chain homologues – but with almost identical properties

Researchers from Harvard University have concluded that PFAS contamination at or above the 1 ppt level is likely to be harmful to human health, based on data about vaccine antibody responses in children. Harvard’s Grandjean, lead author of that study from 2013, says the EPA might not not have considered this work in developing its 70 ppt water guideline. He notes, however, that the evidence of immunotoxic effects associated with PFASs has grown stronger since then. Grandjean says the decision of US states to set their own exposure limits significantly below the EPA’s guidelines has been motivated in part by these immunotoxicity concerns.

Mounting evidence about toxicity and bio-persistence led industry – amid intense EPA and public pressure – to phase out the use and production of PFOS by 2002, and PFOA by the end of 2015. But companies immediately rushed to replace these long-chain PFASs with new short-chain homologues. These contain fewer carbon atoms – typically six or below – but vary only slightly from their predecessors in terms of chemical formula and properties.

Long and short of it

These next-generation PFASs appear to be less bioaccumulative because they generally dissolve in water and so are less likely to build up in the bodies of people and animals. In contrast, the legacy long-chain PFASs that are associated with health problems tend to adsorb to things like soil, sediment or in suspended particulate matter.

The short-chain compounds will stick around just as long in the environment

However, these newer short-chain PFASs are highly mobile in soil and water and are extremely persistent in the environment, which could result in quicker distribution to water resources and faster contamination of drinking water. Research also suggests that short-chain PFASs are actually more resistant to water treatment than their long-chain counterparts, and are therefore more likely to end up in tap water.

‘The short-chain compounds will stick around just as long in the environment, and they would be more mobile in terms of transport in water,’ explains Chris Higgins, a civil and environmental engineer at Colorado School of Mines. ‘Because of that, it would be harder to treat them in drinking water supplies.’ He also notes that the short-chain PFASs are more bioaccumulative in plants, which can lead to ‘additional exposure concerns’. Many experts also point to reports that some long-chained PFASs, like N-methyl perfluorooctane sulfonamide and N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamide, degrade to form PFOA and PFOS, and they note that the chemistry is not well understood.*

For its part, the FluoroCouncil, which represents fluorinated product manufacturers, says it is ‘a misconception’ that the most common replacements for the older, long-chain fluorotechnolgy have similar health and safety issues. The organisation argues that exposure to PFASs in general has not been linked to any specific health outcomes, emphasising it is PFOA and PFOS that have raised such concerns. It is ‘incorrect’, the FluoroCouncil says, to attribute these health effects to other PFASs without first studying them individually. Otherwise, the group warns, bad policy can result that may eliminate valuable chemistries and technology without improving environmental or health outcomes.

Many experts, including Jamie DeWitt, a pharmacology and toxicology professor at East Carolina University whose research has focused on biological responses to PFASs and other contaminants, are sceptical. She maintains that these arguments of the chemical industry are based on ‘limited data’.

PFAS production climbing

Although some animal research has shown that these replacement PFASs may be less toxic relative to the compounds they are intending to replace, DeWitt argues that more data are needed before one can say with confidence that they are safer. ‘We have not fully evaluated all of the ways that they could be toxic,’ she says.

Safety questions aside, the introduction of new short-chain and other PFAS chemicals is continuing unabated, approaching new records. The number of new PFASs produced in volumes greater than 25,000 pounds (11,300kg) a site per year grew in the US from 87 to 118 between 2012 and 2016, according to analysis of EPA data by the non-profit Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. 30 of these compounds were first reported in 2016.

Safe and effective fluorine-free firefighting foams are used throughout major airports across the world

Given the substantial health and environmental concerns associated with the PFAS chemicals, as well as the negative scrutiny, why are they still in wide use? Part of the answer seems to be inertia.

‘They are products of the established petrochemical system and continuing their use is easier and more profitable than developing alternatives based on green chemistry,’ says Tom Bruton, a scientist at the Green Science Policy Institute in California who focuses on highly fluorinated chemicals. Because it was in their interest to continue producing PFASs, he says chemical companies concealed information about the toxicity of PFOA and PFOS for decades. ‘Now that those legacy compounds have been phased out, they continue to downplay concerns about some of the replacement PFASs,’ he adds.

Another reason for the continued pervasiveness of PFASs is that such compounds are sometimes mandated by official policy. For example, the US military’s purchasing standard for firefighting foam specifies the use of fluorinated surfactants. Meanwhile, safe and effective fluorine-free firefighting foams are used throughout major airports across the world, including at Heathrow and Gatwick in the UK, as well as at 27 of Australia’s airports.

Facing the music

Companies that manufacture, use or sell PFASs and PFAS-containing products are facing significant potential liabilities. Firms like 3M and DuPont have been publicly and repeatedly accused of deliberately hiding or spinning internal research that raised serious concerns about the safety of PFASs. Information that has leaked out during litigation has supported such claims.

‘I think the delay in the release of toxicity data from industry relates to a well-documented strategy used in the past: that businesses should not share any information that could hurt the profits,’ Grandjean says.

Many states and cities have taken legal action against PFAS-makers related to pollution, seeking to hold them responsible for remediation and clean-up costs. For example, in February 2018 Minnesota’s attorney general reached an $850 million (£700 million) settlement with 3M after claiming that the company knowingly contaminated groundwater with PFOA and PFOS and damaged natural resources. Under the arrangement, 3M agreed to provide safe drinking water to affected residents and clean up the contamination.

Also in February 2018, Ohio’s attorney general filed a lawsuit against DuPont and Chemours for an unspecified amount over PFOA contamination from its plant on the Ohio River. DuPont filed motion to dismiss the case, and a court decision is pending.

Many other legal challenges against PFAS manufacturers have been fashioned as class action lawsuits, including cases in Colorado, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania. There is also a nationwide claim in Ohio, where a firefighter brought a class action lawsuit against several chemical manufacturers – including DuPont, Chemours and 3M – in October 2018 on behalf of Americans exposed to PFASs.

The complaint alleges that these companies have contaminated the bodies of plaintiffs with substances known to be harmful, and that individuals should not have to wait until actual disease or death occur from this contamination before adequate testing and research is carried out, at an estimated cost of over $5 million.

Separately, DuPont and Chemours paid more than $670 million in February 2017 to settle around 3500 personal injury claims relating to PFOA release from a former DuPont plant in West Virginia into local water supplies. In addition, the companies each agreed to pay up to $25 million a year for the next five years to address further liabilities that might arise. The settlement came after the companies suffered several legal defeats in the first test cases.

For its part, 3M tells Chemistry World that its ‘history of published research and collaboration’ shows that it didn’t suppress scientific evidence regarding PFASs. The company says PFASs play an important role in many applications with industrial or social significance, including electronics, medical devices and low emissions vehicles. ‘We continue to manufacture PFAS compounds today that enable these important applications,’ the company states. However, 3M refuses to disclose which PFAS compounds it’s still making, citing ‘competitive reasons’.

DuPont emphasises that it no longer manufactures or uses shorter-chain alternative products such as the PFOA replacement GenX, saying that is the purview of its spinoff Chemours.

Chemours told Chemistry World that is does not and never has made PFOA or PFOS, not mentioning that it reached a settlement last year with North Carolina environmental authorities after the release of GenX from one of its plants into the Cape Fear River and nearby wells. Under that agreement, Chemours was fined $12 million fine on top of $1 million in investigative costs.

It’s not just companies that are liable. The US Department of Defense has been fighting environmental regulators in several states in order to avoid costly clean-up and remediation efforts. A top agency official has publicly estimated that it will cost more than $2 billion to clean up PFAS contamination around US military bases. The Pentagon has faced public accusations of pressuring the EPA to support weaker regulations for PFAS chemicals, fighting to set the threshold for cleanup at levels that exceed 400 ppt.

A worldwide issue

PFAS drinking water contamination crises are playing out beyond the US. For example, communities across Australia have in recent years reported PFAS pollution near military sites that used fluorinated firefighting foam for decades. As a result, the Australian defence department has been the subject of numerous class action lawsuits. The Australian health-based guideline for PFOA in drinking water is 560 ppt, and 70 ppt for the sum of the concentrations of PFOS and perfluorohexane sulfonate acid (PFHxS).

Regulating total PFASs would be a bold step, but also a practical one

Europe is also in the thick of it. More than a decade ago, contamination from perfluorinated compounds was uncovered in the waters and sediments of major European rivers. The highest concentrations of PFOA have been found in the river Po in Italy’s Veneto region, where ground water, surface water and drinking water has been contaminated with PFASs. In fact, earlier this year a new type of PFAS turned up in the Po, with the suspected culprit being the Miteni chemical plant in that region. Chemours had reportedly sent some of its PFAS waste from the Netherlands to Miteni between 2014 until 2017, or even more recently.

Last year, the EU proposed revising its drinking water directive to include limits for individual PFASs and the entire class of chemicals. This revision, which is not yet law, would mandate that individual PFASs cannot be above 100 ppt, and the sum of total PFASs cannot be above 500 ppt in drinking water. Although these safety values are significantly higher than those of the US EPA, they are dramatically lower than the World Health Organization’s recommended levels of 4000 ppt for PFOA and 400 ppt for PFOS.

‘Regulating total PFASs would be a bold step, but also a practical one, given the large number of individual PFASs that have been detected in drinking water,’ Bruton says. The EU proposal must be negotiated between the European Parliament and the EU Council. There is some resistance, in part because of the lack of an agreed analytical method for measuring total organic fluorine, a source tells Chemistry World.

Billions of euros at stake

The annual health-related costs of addressing fluorinated substances contamination for EEA countries, including the UK, are between €52–84 billion (£48–77 billion), according to analysis from the Nordic Council in March. In addition, the Nordic Council expects that the European-level costs for remediating some cases of contamination will be in the hundreds of millions of euros or more.

More than 180 governments agreed to a global ban on PFOA and related substances – but not the US

There is currently no Europe-wide health advisory level for PFASs in drinking water, and member states have taken action on their own, like US states. Germany and Sweden are at the forefront, proposing to ban six PFASs and other compounds that can be degraded to one of those six under the EU’s Reach legislation, which regulates chemicals made and sold in Europe. This restriction will effectively cover about 200 PFASs, the Swedish Chemicals Agency has estimated. In addition, Sweden’s national food agency has instituted a non-binding action level of 90 ppt for the sum of 11 PFAS compounds in drinking water.

The winds of change are blowing. After representatives from more than 180 governments met for the ninth Stockholm Convention conference in Geneva in early May 2019, they agreed to a global ban on PFOA, its salts and more than 150 related substances. Delegates from these countries, including those of EU nations, also formally agreed to prohibit the production, export or import of PFOA-containing firefighting foams and their use in training, with a five-year phase-out period, according to IPEN, a global network of NGOs and public interest groups focused on eliminating persistent organic pollutants. The US is not a party to the convention, so the bans do not apply there.

The participating governments also instituted a five-year deadline to end PFOS use in firefighting foams, and to prohibit its production, export or import and use for training. ‘They also warned against the use of the short-chain PFAS replacements and recommended the use of fluorine-free foams,’ adds Pamela Miller, one of IPEN’s leading PFAS experts.

Regulation is often considered anti-business. However, in his closing remarks before the ACS conference, Dichtel said companies responsible for PFAS contamination, like 3M and DuPont, would have been in a great position to develop new and innovative technologies that didn’t use PFAS compounds, had they acted instead of obscuring the problem for decades. ‘I think our enterprise and our world would be much better off,’ he told the audience.

*UPDATE 28 August 2019: This sentence was amended to clarify the degradation of long-chained PFASs into PFOA and PFOS

1 Reader's comment