Intrepid researchers will brave the harshest conditions in the name of science. Ned Stafford talks to some of Antarctica's chemists

As a child, Rolf Weller dreamed of adventure. But by the 1980s - studying physical chemistry at the University of Heidelberg in Germany - he was resigned to the fact that exotic destinations would not feature in his professional future. ‘I thought chemistry was a discipline where you stay in the laboratory,’ he says. ‘Geologists work in the field, not chemists.’

But he was wrong. After his PhD he took a position at the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany. That was in 1989, and he has since made eight expeditions to Antarctica and several to the Arctic region. Weller is now scientific manager of the Wegener Institute’s air chemistry observatory at Germany’s Neumayer Station in Antarctica. The vast continent is, he says, earth’s most exotic location.

Some 98 per cent of Antarctica is covered by flat sheets of ice that average 1.6km in thickness. ‘It’s like another planet,’ Weller says. ‘There’s nothing but ice. You can only see white and the blue heaven and it’s absolutely noiseless. If you hike a couple of kilometres from the station, you can hear your heartbeat.’

Back in the 1980s, there was some truth in Weller’s assessment that Antarctica was primarily a field for geologists. But today, as concern mounts that climate change could trigger an ecological nightmare later this century, global leaders are looking to science to provide solutions. Chemists are leading the charge in Antarctica, studying the continent’s relatively pristine air and boring deep into layers of ice - some dating back 800,000 years and holding chemical traces of past climate change that could provide answers for our future.

Something in the air

Neumayer’s air chemistry observatory, part of the Global Atmosphere Watch programme, continuously monitors and records gaseous and particulate trace components of the troposphere. The atmosphere above Antarctica is the cleanest part of the Earth’s troposphere, largely free of aerosol and trace gas sources, making it a huge clean air laboratory with natural conditions comparable to pre-industrial times. In addition to the troposphere, Neumayer’s air chemistry observatory also measures aspects of the chemistry of snow and firn, as well as the stratosphere and upper troposphere. By studying the chemical characteristics of the current atmosphere and how it is transferred to snow and ice, scientists will better be able to interpret ancient ice core records.

Eric Wolff, a glacier chemist and principal investigator for climate and chemistry at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) in Cambridge, UK, agrees that chemists play leading roles in the study of the Antarctic atmosphere and ice cores. And, he says, chemistry is a crucial part of most other BAS divisions and departments, including geology, biology and oceanography. ‘There is a lot of very interesting chemistry going on in Antarctica,’ he says.

But work on the continent is very dependent on the season. Most chemists arrive in October or November for a polar summer of research, and return home in time to enjoy the blossoming of the Northern Hemisphere spring. There are around 4000 scientists and support personnel there during the summer, but that drops to around 1000 people in winter.

Kathy Welch, geochemist at the Byrd Polar Research Center (BPRC) at Ohio State University in Columbus, US, has journeyed to Antarctica for each polar summer since 1993 and plans to make her 16th trip later this year.

She and BPRC colleagues are based at McMurdo Station, a US-operated research centre at the southern tip of Ross Island on the shore of McMurdo Sound, 3500km south of New Zealand. By Antarctic standards, McMurdo is a vibrant metropolis, capable of supporting over 1200 residents.

‘There is an amazing community of people there,’ Welch says. ’Most people who go to Antarctica have an adventurous spirit, but the scientists are also serious. The community is dynamic and every year there is something different happening.’

The BPRC is 15 years into a long-term ecological study of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, a polar desert ecosystem about 30 minutes by helicopter from the station. The team collects samples, including soils, sediments, rocks, water, ice, and algal mats, for chemical analysis. Welch focuses on hydrologic systems - analysing water samples from the glaciers, streams, ponds, and lakes in the dry valleys. ‘We want to understand how the ecosystem is responding to changes in climate,’ she says.

Even in the Antarctic summer field research can be difficult. ‘It’s not like any other place on earth,’ says Welch. ‘Sometimes, just going outside to collect samples, following procedures and writing good field notes can be difficult because of wind or cold conditions.’ But it is a good place to get work done: ‘there aren’t many distractions, so we work fairly long hours.’

Most samples are analysed in the Crary Laboratory at McMurdo Station, a modern climate-controlled facility. ‘Some of the challenges come from the samples themselves - they can span many orders of magnitude in concentration,’ Welch says. ‘We analyse everything from pristine glacial ice to hypersaline lakes.’ A major focus of her research is tracking the movement of carbon and nutrients through the ecological system.

At the slightly more subdued BAS Halley Station, about 70 people are present in the summer from November to February, with only about 16 people - mostly support personnel - spending the winter. The station, like nearly all others in Antarctica, is virtually inaccessible to the outside world between April and October. For 105 days at the height of the Antarctic winter, the sun does not rise above the horizon at Halley. And while on sunny summer days temperatures can rise to a balmy 0°C to -10°C, in the winter temperatures normally stay below -20°C with extreme lows of around -55°C.

This means that for chemists and their equipment, conditions are far more challenging than in the laboratory. Wolff explains: ‘Even simple components like pumps have to have tolerances that allow them to work at maybe -40°C. So equipment has to be chosen very carefully.’ BAS has large freezers in Cambridge used for testing and adapting equipment for use in Antarctica.

Extreme equipment

According to Wolff, field spectroscopic gear, which automatically scans various angles above the horizon, has moving parts that must be adapted for the cold. They must be coated with greases made specifically for extremely low temperatures. Reflectors - used to reflect light emitted by long-path spectrometers - tend to collect snow and frost in Antarctica, so they need to be heated when in use.

And beta-glactosidase, an enzyme used to analyse sodium in ice cores by continuous flow methods, won’t function at temperatures below -20°C, so in Antarctica the enzyme has to be kept warm. Back in the Cambridge laboratory it has to be cooled.

The extreme weather conditions in Antarctica and the difficult - and in winter impossible - accessibility, means that laboratories and supply rooms must be overstocked with spare parts and chemicals. ‘In Cambridge, we might have to wait a day or two for a spare part to be delivered,’ Wolff says. ‘In Antarctica, you might wait a month or two, even a year. You have to be prepared, like in no place else in the world.’

Those determined souls who spend the winter in Antarctica - the ‘winterers’ - have to be prepared to endure 14 to 15 months away from home in one of the most inhospitable climates on earth. And while winterers now have satellite telephone and internet access to communicate with the folks back home, Antarctica in the winter can be bleak and lonely.

Weller is involved each year in selecting an air chemist to spend the winter at Neumayer Station as part of a nine or 10-person crew. In addition to the air chemist, the crew includes a medical doctor, a meteorologist, two geophysicists, a station engineer, an electrician, a communications engineer, and a cook.

Teams are selected by May and members given two year contracts beginning 1 August. Team members normally arrive in Antarctica a few months later in December, when Neumayer is swelling up with summer scientists and personnel, Weller says. The old team of winterers remains at Neumayer until around February, helping to train the new team. By March, the old team and summer residents are gone. The nine new winterers are alone with no way to leave until the following November when flights begin again. After a year in Antarctica, the now veteran team trains the new team before leaving for home in February or March.

Life in the wilderness

Thanks to the internet and improved - and less costly - satellite phone service, daily life for scientists in Antarctica is not nearly as isolated as it was only a few years ago.

‘Keeping in contact with family and friends at home takes more time than one would think,’ says Franziska Nehring, an air chemist at Neumayer. ‘I can’t imagine how it must have been in former years where there was no talking on the phone or writing emails.’

British Antarctic Survey glacier chemist Eric Wolff doesn’t have to imagine. He first set foot on Antarctica in November 1979 staying until early the next year. While most scientists now fly in, he travelled by ship - a total seven months away from home. No phone calls, no e-mails only telex messages. ‘I was allowed 200 words of telex each month to my girlfriend,’ he says. ‘She had 200 words each month as well.’ These words must have been well chosen, as the then girlfriend is now his wife.

Antarctica’s new generation of scientists have it much easier. ‘You don’t have to be a roughie-toughie anymore,’ says Wolff.

BAS tropospheric chemist Neil Brough says the Halley Station has a pool table, dart board, DVDs, library, a bar, and gymnasium for him and his 16 colleagues. And, of course, outside there is never a lack of snow for cross-country skiing and snowboarding, or a lack of space for jogging - as long as you wrap up warm.

Each evening a group event is planned - there are movies two evenings a week or German, French or Italian language classes. Friday night is reserved for wannabe rock stars putting on a show with guitars and drums. ‘There is always something happening,’ he says.

Neumayer air chemist Karin Smolla says that in addition to movies, cards and games, her group of nine winterers had a ballroom dancing course each week. And Neumayer even has a sauna that is fired up two evenings a week.

Smolla says the food was ‘pure delight’, prepared by a former ship cook, who each Sunday evening treated the group to a candle-lit three course meal with wine. The recruitment of a chef to an Antarctic research station is a serious business. The Halley cook, Brough says used to be an in-house chef for a global pharmaceutical firm. ‘Beautiful meals,’ he says. ‘[He] can prepare anything.’

The countdown

Before their trip, team members train in the Austrian Alps. There is no age limit, but the medical and physical tests are stringent - most team members are single and under 40 years old, according to Weller. After about a week of intensive training, each member is asked privately if there is anyone on the team they could not spend an Antarctic winter with. Even if only one person labels a fellow team member as ‘unbearable,’ then that person is removed from the team and a replacement called in. This has happened twice in the past 10 years, Weller says.

Despite this safeguard, he adds, tensions do sometimes arise during the Antarctic winter. ‘There are times competing groups and subgroups are formed, and maybe two people don’t speak.’

The medical doctor at Neumayer is always the designated station chief, with ultimate decision-making authority. ‘The others have to obey the doctor,’ explains Weller. At the BAS Halley Research Station, officials in Cambridge choose the member they believe is best suited to be winter base commander, and that person is sworn in as a magistrate.

Weller says Neumayer support personnel often are former sailors, accustomed to long stretches of time away from home in close quarters. Indeed, the current Neumayer II station, to be replaced later this year with the new high-tech Neumayer III station, is buried under snow. ‘It’s like living on a ship,’ he says.

Karin Smolla was working in the Austrian Alps as an environmental chemist when she saw the Wegener Institute’s advertisement for an air chemist in Antarctica. Smolla grew up in Germany, but loved the snow, ice and cold of the Austrian Alps. ‘I saw the ad and said, "this is for me."’

She arrived at Neumayer in December 2006 and did not leave until February of this year. ‘Never, during all that time, did I regret being there,’ she says. ‘It was like a dream come true.’

Smolla was responsible for the air chemistry observatory, which is about 1.5km away from the main station in order to avoid air contamination. She worked from three to 10 hours a day seven days a week. Her work included ensuring that highly sophisticated equipment functioned properly; changing air filters; and collecting, labelling and storing air samples for the later flight back to the laboratory in Bremerhaven.

The team also shares housework, which includes shovelling snow to be melted and purified for drinking water and other uses.

Neil Brough, tropospheric chemist at Halley Research Station from November 2006 until the end of March this year, managed the clean air sector laboratory (CASlab). Like others who have been to Antarctica, Brough was beguiled by the continent.

‘It is beautiful,’ he says. ’Totally white; totally isolated. At night there are so many stars. And the auroras - sometimes someone will yell, "aurora," and everybody goes outside to watch. It is breathtaking: the colours - red and purple and green - float like a veil in the sky. Antarctica really did blow my mind.’

But unlike Smolla, who hopes to spend a second year there, Brough admits that once was enough for him. ‘It was a long 16 months,’ he says.

He describes his job as ‘operating and maintaining a whole suite of complex, state of the art scientific equipment.’ Readily available commercial instruments are used for standard measurements of chemicals such as carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen oxide or dioxide, black carbon and aerosol. But Brough says some instruments have to be modified or custom-built for the Antarctic to measure more specific chemical species, such as the actinic flux spectro-photometer, used to measure photon intensity. Much of Antarctica’s atmospheric chemistry depends on the level of light available in the summer (or lack thereof in the winter) so it is important to quantify levels available for this photochemistry.

Another example of a modified instrument is the so-called mini max DOAS (mini multi-axis differential optical absorption spectrometer), which is used to measure halogenated compounds, such as bromine radicals. This is an important measurement because BrO and IO values are high in the Antarctic, and this has several chemical effects, including the destruction of ozone.

Like the air chemistry observatory at Neumayer, to avoid contamination from the main Halley station the CASLab is located 1.5km away. Most of the instruments measure in real time and are adjusted and calibrated on site throughout the year. Snow samples are taken at regular intervals, stored and then later shipped to Cambridge for testing.

The chemist on site must also deal with breakages or other problems. If no spare parts are available, then either the system configuration is redesigned, the damaged spare part modified, or a new spare part built at the station’s large electronics and mechanical workshop.

But despite careful planning, says Brough, there are always complications due to the [Antarctic] environment: ‘there are many problems caused by the wind, temperatures and snow.’

Bad weather can often hinder or cancel the walk or ski trip to the CASLab, he says. Sometimes snow ingress blocks gas sampling inlet lines or blizzards cause electronic and power failures. ‘Conditions can make work outside very demanding and time consuming. Just holding a spanner for a few minutes can cause enough of an issue that you have to return to the laboratory to warm your extremities.’

Wolff, who oversees CASLab from the comfort of Cambridge, says it is essential to have a highly qualified chemist at Halley over the winter. ‘The person has to be able to react to data and be competent to tell us what is happening,’ Wolff says. ‘If he doesn’t understand it, he can’t explain it to us.’

Wolff says finding top chemists is not difficult. ‘The science is topical and in demand,’ he says. ‘Someone like Neil gives up a year of his life, but if all goes well half a dozen papers bearing his name will come from the year he spent. And, of course having been to Antarctica makes your CV stand out from the crowd.’

Ned Stafford is a freelance science writer based in Hamburg, Germany

The Antarctic toolbox

Along with some precision scientific instruments, a glacier chemist’s toolkit contains some simple but essential utensils common to bartenders, cooks and deep water well diggers. An ice crusher, for example, is vital, says British Antarctic Survey (BAS) glacier chemist Eric Wolff.

And before the ice crusher can be used, chemists often use an enormous drill - 4.6m long and weighing 85kg - to take ice core samples of 10cm in diameter at lengths of about 3m. The deepest drills can be up to 3000m long. To extract ice cores from metal tubes and remove potentially contaminated ice, the chemist places tubes on a long hot plate - an oversize version of what a restaurant kitchen might use - rotating the tube to melt the ice and remove contemporary impurities, then sliding the pure inner ice out.

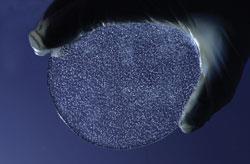

The ice is put into a vacuum chamber and the ancient air is released from the bubbles with an ice crusher, Wolff says. The BAS was part of the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) team retrieved two deep ice cores dating back 800,000 years.

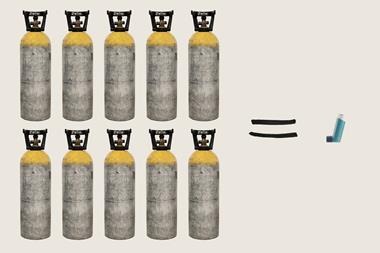

The air chemist’s toolbox is very different. BAS tropospheric chemist Neil Brough says it can vary from year to year, depending on research focus. The kit for his 16 months in Antarctica included:

-

Chemical ionisation mass spectrometer

-

Carbon monoxide fluorescence analyser

-

Ultraviolet photometric ozone analyser

-

Actinic flux spectro radiometer

-

NOx chemiluminescence analysis

-

Differential optical absorption spectroscopy

-

Condensation particulate counter

Franziska Nehring, air chemist at Neumayer until the first quarter of next year, says her tool kit includes similar devices. At the heart of her lab are devices for high volume sampling of aerosols and radionuclides, and low volume sampling for reactive trace gases. The lab also include a cryogenic trap for water vapour and a CO2 trap, which relies on the absorption of CO2 by NaOH, she says.

Nehring’s air chemistry lab is in a container building on a platform about 3m above the snow surface and is about 1.5km south of Neumayer station. So her tool kit must also include camping equipment, and life-saving food and warm blankets, just in case bad weather makes the hike back to Neumayer station impossible.

No comments yet