The European witch hunts claimed thousands of lives, but behind the accusations lay a complex relationship between chemistry, medicine and magic. Victoria Atkinson explores how plant alkaloids and traditional knowledge created potent remedies that were both feared and sought after.

-

Historical witchcraft may have roots in chemistry: Many so-called magical practices and potions used by accused witches were based on plant compounds with real physiological effects, such as alkaloids that cause hallucinations or act as medicines.

-

Witches as early empirical scientists: Despite lacking formal education, many women practiced forms of herbal medicine and empirical chemistry, using fermentation, extraction and transformation techniques to create effective remedies – often misunderstood or feared.

-

Social and gender biases shaped persecution: Most accused witches were lower-class women practising healing arts without formal recognition, and societal upheaval during the Reformation amplified fear, suspicion and binary thinking, leading to widespread witch hunts.

-

Modern relevance and legacy: While alchemy is acknowledged as a precursor to chemistry, the contributions of witchcraft are often ignored. Yet many plant-based remedies used by witches – like galantamine and St John’s wort – remain relevant in modern pharmacology.

This summary was generated by AI and checked by a human editor

There’s something compelling about witchcraft: from the three witches of Macbeth to the magical world of Harry Potter, the idea of magic has captivated us for centuries. Modern thinking has placed the occult firmly in the realm of fiction, but earlier belief in and fear of the malevolent acts of so-called witches whipped people across the world into a frenzy, with devastating consequences for the accused. Claims of black magic and collusion with the devil cost an estimated 50,000 people their lives in the European witch hunts between the 15th and 18th centuries. But could there have been something more scientific behind these stories than just fear and superstition?

The popular image of a witch – that of a poor old woman hunched over a bubbling cauldron – dates back to the European trials, but the notion of witchcraft and magical potions is in fact much older, according to witchcraft historian Marion Gibson from the University of Exeter, UK. ‘Witches and magic go all the way back as far as recorded history, but people did think about them differently in different cultures,’ she adds. ‘In Greek and Roman society, people believed that some kind of magics were OK but others not, and they started to equate witches with poisons and people who use poisonous compounds in medical matters: right from the earliest times that we have records, people have been suspicious of the connection between magic, medicine, and poisoning.’

Rooted in reason

The idea that these seemingly fantastical concoctions of dried plants and unusual animal extracts may have had some kind of physiological effect is entirely rational, says phytochemist Michael Wink from the University of Heidelberg in Germany. All organisms produce secondary metabolites, compounds which are not essential for growth and life but which enable the organism to interact with its environment. For plants in particular, many of these compounds are associated with survival and defence. ‘Plants are surrounded by animals, bacteria, fungi and viruses, all which try to kill them. So the solution of evolution was to produce toxic chemicals. For example, if you look at alkaloids, most of them are very strong neurotoxins,’ explains Wink.

These compounds evolved to interact with hundreds of different biological targets, corresponding to a whole spectrum of effects in humans, from sedation to hallucinations. Consequently, people have been experimenting with plants since prehistoric times. But with no knowledge of this underlying chemistry, the miraculous (or horrifying) effects were often ascribed to magic.

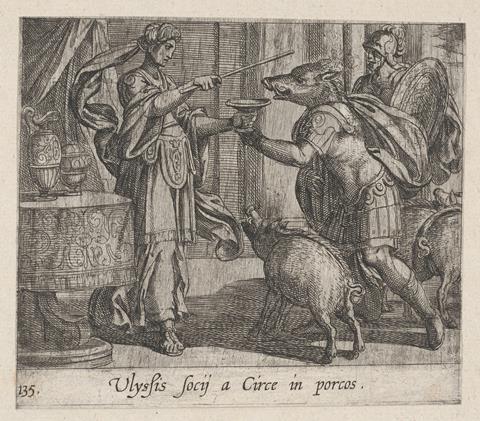

One of the most famous examples of this is the tale of the sorceress Circe who transformed Odysseus’s men into pigs with poisoned wine. There’s an element of conjecture in disentangling the truth from these stories – often specific plant ingredients are not mentioned and the important details can become masked behind the mysticism and ritual. But working backwards from the results of this alleged magic and the plants known to be available in the area at the time, it’s possible to reconstruct the chemistry that may have informed the myth.

Although Circe is a character from Greek legend, medical historians have speculated that the poison in her wine probably refers to jimsonweed, one of many plants, including nightshade and mandrake, which contain tropane alkaloids. The transformation into pigs could therefore be understood as hallucinations and delusions triggered by alkaloid intoxication, rather than a literal event.

‘The target is the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, and the tropane alkaloid just blocks that. At a higher dose it kills you but at a lower dose you just get funny visions,’ explains Wink. ‘First of all users fall into a deep sleep, dreaming heavily. When they wake up, and this is the important thing, people believed the visions were real – it’s a very strong hallucination.’

This theory is further borne out by later events in the story. After his men are transformed, Odysseus is instructed by the God Hermes to take an antidote – a plant called moly with white flowers and black bulbs. ‘It’s quite clear it must be an antidote to the acetylcholinesterase and the antidote is another alkaloid called galantamine, from the snowdrop,’ says Wink.

Tropane alkaloids are probably responsible for one of the other big stories surrounding witches. ‘One of the persistent myths that comes up is that they have this flying ointment. So they smear something on themselves to fly through the air,’ says Gibson. ‘If you go back to the original sources, the ointment is said to contain aconite and belladonna’ – which would induce hallucinations of flying – ‘but also a bunch of other ingredients including ash and baby fat.’

However, once again these outlandish claims are rooted in organic chemistry. Within the plant itself, the alkaloid exists in the form of a hydrophilic salt. But in order to penetrate the skin and cross the blood–brain barrier, the compound must pass through lipid membranes. ‘Therefore you have to convert the alkaloid into the free base, which is lipophilic,’ says Wink. ‘They hadn’t any clue about the chemistry but they knew if they added ash (which is alkaline), it would be more potent.’

Mixing this residue into some fat would then allow the free base to pass through the skin and dissolve in the blood, making the active compound bioavailable. It’s extremely unlikely that these preparations involved genuine baby fat, adds Gibson: these claims were all part of the wider perception that witches were evil anti-mother figures.

Wise woman or witch?

But while these are the stories that have persisted, the day-to-day activities of the people accused of witchcraft were likely very different. ‘A lot of the people who were drawn in were involved in some kind of magical–medical, what they call cunning practice, and would have seen themselves as healers of one kind of another – herbalists, midwives, children’s nurses etc,’ says Gibson.

The services offered by these practitioners were extremely varied: spells, charms and talismans, ointments, potions, poultices. And while some were clearly just hocus pocus – ‘There’s a particular spell that uses some shears in a sieve and they whirl it around and it’s like a compass to tell you who bewitched you,’ describes Gibson – there’s reason to suppose others may have indeed had at least some part of the advertised effect (see box A spell to cure lameness below).

But Gibson cautions that evaluating the efficacy or even the specific composition of these mixtures scientifically is a tricky issue to navigate. ‘It’s all very anecdotal and you’ve got two problems,’ she says. ‘One is that the records are extremely limited because this knowledge was orally transmitted. And the second is that when people did make a record, they were grappling with their own level of medical knowledge, their own prejudices, their own religious perspective and their own beliefs about magic. So when you do get a record, it’s very skewed, it’s very partial, and it’s difficult to say anything authoritative about whether it worked.’

But despite the lack of written records created by practitioners themselves, other sources such as household books kept by higher-status women, archaeological finds like witch bottles, and monastic records help shed light on their activities by revealing the plants they used and the ailments they treated.

‘In the mediaeval ages they probably had 400 species of plants they were using,’ says Wink, listing a few: ‘Yarrow is full of essential oils and chamazulene, a very strong anti-inflammatory, and people used it for many things but especially for infections of genital parts. Then we have agrimony, full of polyphenols and used against skin diseases, inflammation, if you had a sore throat or if you had diarrhoea. Horseradish, a plant full of distinct pungent compounds, was used to treat infections of the kidney, ducts and bladder. And Juniperus sabina or savin is one of the most potent abortifacient plants and contains some terpenoids which are cytotoxic.’

All of these plants were native to Europe during the 15th century. But preparing them in such a way that they were both efficacious and safe required extremely specialised knowledge, possibly contributing to the fear and awe with which these women were viewed.

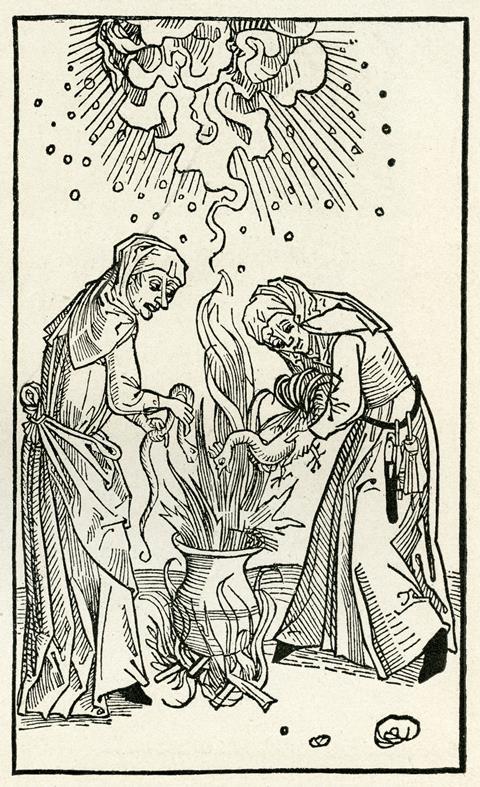

‘A number of secondary metabolites are present in the plant as a prodrug. So they are stored in the vacuole mostly as a glycoside – the main compound with an added sugar,’ explains Wink. ‘To obtain the active compound, you have to split off the sugar. The hydrolysis can be achieved by fermentation. This was found empirically.’ Aqueous extracts, created by boiling the plants in water, were left standing over several days, allowing the prodrug to slowly degrade into the active component. Similarly, other plant samples were transformed into effective medicines by drying, grinding and steeping.

Much of this feeds into the popular image of witches. Many homes would have had a cauldron in the kitchen and knives, strainers, churns, wooden barrels, and even metal vats were relatively commonplace tools in agricultural households. ‘They worked a lot with processes that transform ingredients in one way or another, for example making cheese or beer,’ says Gibson. ‘That must have seemed quite a potent position, surrounded by all your magic kit which transforms matter.’

A spell to cure lameness

Few records exist of the spells and potions employed by witches – as the population was largely illiterate, their specialised knowledge and secrets were shared orally amongst a select few. However, witch trials were a formal legal proceeding and verbal accounts given by disgruntled neighbours were often recorded in official court documents. One such trial pamphlet from the examination of Ursley Kempe of Essex in 1582 recounts a spell purported to cure lameness (reworded into modern English):

Knead together hogs’ dung and chervil then hold it in the left hand, prick it with a knife three times, and throw it into the fire. Then take the knife, make three pricks under a table, and let the knife stick there. After that, take three leaves of sage and as much of herb John, put them in ale and drink it last at night first in the morning.

While the ritualistic half of this spell is almost certainly hocus pocus, could either sage or St John’s wort have alleviated the patient’s symptoms?

‘Sage, Salvia officinalis, is a traditional herb which is very active and it has lots of essential oils and phenolics. It’s known to be antispasmodic and used to treat spasms, colic and flatulence. If your lameness is caused by spasm, it could help,’ says Wink. ‘St John’s wort was used to treat inflammation of the skin and wounds, not as an antidepressant as we do today.’ Potentially then, this component could relieve symptoms of inflammation.

Without more reliable records, we can only speculate about the actual effect of this spell. But another hypothesis is that perhaps these types of magical cure were just a placebo. ‘These people listened to the patient and their role was something like a modern therapist,’ says Gibson. ‘They would sympathise and give you something to take away that supposedly would help and that can be really psychologically powerful.’

Accusation to execution

For the majority of society, the local wise woman and her remedies would have been the only option in times of need, so what caused so many to turn on their neighbours? Gender politics almost certainly played a part, says Gibson – over 75% of those accused of witchcraft were women, typically from a lower social class.

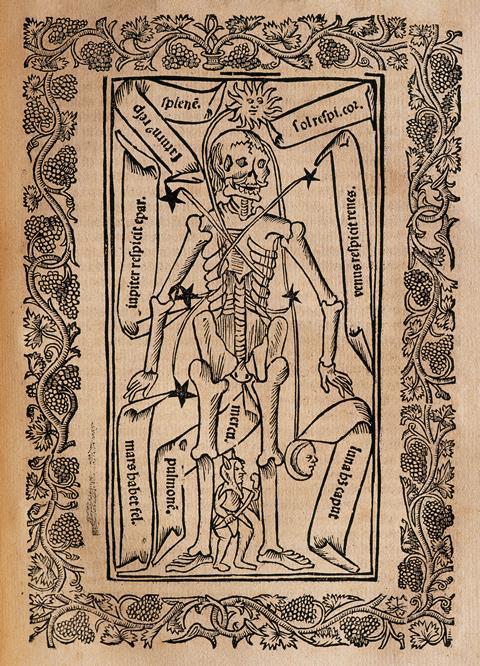

The prevalent belief amongst clergy and physicians that women should confine themselves to other areas also led to suspicion that anyone else practising medical trades was inherently dangerous. ‘For example, there’s a woman in the early 1600s who provides this medical textbook which has a drawing of the human body with all the veins and bones, and this is held up against her as evidence of magic,’ describes Gibson. ‘With no access to formal accreditation or formal education, there was no way she could be called a physician or an apothecary so she ended up being labelled a witch instead.’

But the timing of the witch trials in Europe is possibly symptomatic of a wider societal problem. The rise in suspicion, accusations, and ultimately executions coincides with the beginning of the Reformation in the early 16th century. ‘People start to have a wobble about religion. They’re becoming confused and frightened because now they have two big Christian religious choices and what if they pick the wrong one?’ says Gibson. ‘It’s a time when people’s trust in each other breaks down. They start thinking in far more binary terms – it’s either good or evil.’

Fast forward 200 years and the greater religious tolerance which characterised the 18th century, coupled with the scientific advances of the industrial revolution led to a decline in accusations and witch hunts in England (see box Witchcraft around the world below). But despite this reprieve, much of the knowledge held by ‘witches’ was lost in the process. ‘It was entirely orally transmitted and it was associated with people who were not believed to have a stake in science, ie women,’ says Gibson.

Witchcraft around the world

While western medicine now rationalises the curative properties of plants through chemistry not magic, belief in witchcraft and persecution of its practitioners is still prevalent in other parts of the world. Spiritual and herbal healing is a core tenet of many traditional cultures including the Maya people of Guatemala, the Sangamus of Malawi and the islanders of Siquijor in the Philippines, and these mystic customs are frequently practised side by side with modern medicine.

Distrust and suspicion of these rituals from other communities (often on religious grounds), however, means accusations of malevolent magic, and the corresponding pursuit of these healers and herbalists remains an important modern issue. ‘It’s still happening and we have cases of witch-hunting, violence and even murder from diverse countries and diverse settings, so in no way is this something which has disappeared completely,’ says Michael Heinrich, an ethnopharmacologist at University College London, UK. ‘But it’s not really about the chemistry here. Unfortunately, it’s about the social relations.’

Modern magic

So does any legacy remain of these women’s work?

While alchemy, which was commonly practised amongst socially elite men during the same period, is widely celebrated as the forerunner to chemistry, the contributions of witchcraft to our understanding are largely overlooked. Once again, the biases of class and gender have shaped our perceptions of these pre-chemists: the alchemist was an erudite and scientific gentleman while the witch was a sinister or mad old crone. But unlike efforts to transform lead into gold, plant natural products remain an important topic in chemistry today.

‘Many of the alkaloid-containing plants are still very important as medicines and these are sources of the primary material used medically,’ says Heinrich. ‘Galantamine is used in the management of Alzheimer’s and there are lots of studies now on isolated psilocybin metabolites as antidepressants.’ Even traditional herbal medicines remain popular in the treatment of minor conditions: valerian for poor sleep, St John’s wort for low mood, arnica for bruising and inflammation. ‘There’s a lot going on right now in self treatment,’ he adds. The only difference is now we know how and why these treatments work.

Perhaps then, chemistry has broken the spell of witchcraft, explaining the extraordinary at the most fundamental level. But on the other hand, what is a modern drug if not a scientific potion?

Victoria Atkinson is a science writer based in Saltaire, UK

No comments yet