What began as one chemistry professor's project to find the 10 most important molecules of the 20th century, has brought science and art together in a unique exhibition

What began as one chemistry professor’s project to find the 10 most important molecules of the 20th century, has brought science and art together in a unique exhibition

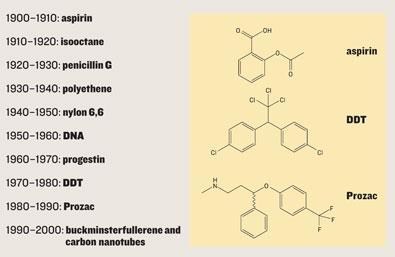

Organic chemistry changed our world in the 20th century. It gave us miraculous cures for disease and revolutionary new materials that defined modern life. As part of a chemistry outreach program for liberal arts students at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York in the US, chemistry professor Ray Giguere set out to identify the

10 molecules that made the greatest impact - one for each decade. The project grew to involve an advisory committee of eminent chemists from throughout the country, and a range of collaborators from social sciences and the arts. The Philadelphia-based Chemical Heritage Foundation (CHF) joined the initiative, bringing funding, and insights into the historical context of the chemical developments. The work has culminated in an exhibition currently at the Tang Teaching Museum in Saratoga Springs, exploring the social, scientific, and artistic aspects of 10 Molecules that Matter.

The exhibition immerses you in organic chemistry. ’Molecules are hanging off the ceilings and the walls,’ says Giguere. As a synthetic organic chemist his work is driven by molecular structure. ’I’d like people to appreciate not only the utility, but also the beauty of these molecules.’ Co-curator John Weber, director of the Tang Museum, agrees: ’As we moved the structures around looking for ways to arrange the exhibit, I was struck by how visual organic chemistry is.’

The exhibition explores ideas of beauty, meaning, and cultural significance in chemistry through the work of 15 contemporary artists. Malissa Gwyn, assistant professor of art at the University of California, Santa Cruz, US, has been exploring the interface of science and art for several years. ’My early work was inspired by the utility and beauty of molecular models,’ she says. ’Scientists have developed imaging systems to reveal the deeper structures. The perception of beauty is looking for something that we can’t see yet - revealing the hidden meaning.’

Roald Hoffmann, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry (1981) was one of the judges involved in choosing the 10 molecules. ’Molecules can be beautifully simple and simply beautiful,’ he says. ’But, chemists and artists know that there is infinitely more to beauty than simplicity.’ He cites the complexity of biochemical molecules such as haemoglobin as an example. ’Beauty resides not just in simple things, but at the tense edge where simplicity and complexity, where symmetry and asymmetry, where chaos and order contend with each other.’

Robert Hargrove, professor of chemistry and environmental science at Mercer University in Atlanta, US, and one of the exhibition’s science advisory committee members, was struck by similarities between the artistic and scientific endeavour. ’The public perception is that we just come into the laboratory and make a new material,’ he says. ’The reality is that science is mostly about failure - we follow many dead-ends. The artists understand this too. It takes time to get it right.’

Medicinal chemistry

Salicylic acid from willow bark was used for centuries as a pain reliever, but the pure acid irritated users’ stomachs. At the turn of the 20th century Felix Hoffmann, working for Bayer AG, Germany, developed a commercially viable synthesis for acetylsalicylic acid, solving this problem, and Bayer launched its ’wonder drug’, aspirin.

The meteoric rise of medicinal chemistry revolutionalised the treatment of illness and millions of people are alive today as a result. But some are now dependent on the drugs. ’My work explores the love/hate relationship between people and the prescription drugs on which they depend,’ explains Jean Shin. ’Pill containers were donated to me by individuals who must take these drugs every day - every bottle has a story.’ The bottles are connected together to suggest the bars in a bar chart of drug use in the US. They are mounted on mirrors on the floor and ceiling of the Tang museum. ’If you look up or down you see a line of pill bottles stretching to infinity,’ says Shin. ’The installation hints to a fragile life-line of dependency and over consumption of drugs in our culture.’

The freedom to travel

The decision about which 10 molecules to include was not an easy one to reach. It was a lively discussion involving the students, a scientific advisory board, and two Nobel laureates. ’I put in a particular vote for isooctane,’ says advisory board member Mary Ellen Bowden, senior historian at the CHF. She wanted to recognise the role that motor vehicles and fuels derived from crude oil played in the 20th century - reconfiguring the design of cities, reshaping social relationships and impacting global warming and global politics. The identification of isooctane as the first anti-knocking agent by scientists at Ethyl Corporation in the US was the key development leading to these changes.

Penicillin

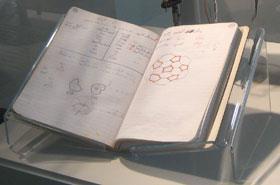

Before the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1924, and its development as a drug by Howard Florey and Ernst Chain at Oxford University, UK, in the 1930s and 1940s, sulfonamides provided the only options for treating bacterial infection. They were toxic to three per cent of the population.

New materials

In 1933 chemists at ICI, UK, created polyethene (initially by accident). The company launched the new material in 1939, and the first production plant began operation on the day that Germany invaded Poland. It immediately found wartime application as insulation for radar cables, and became a military secret as a result.

Nylon 6,6 also made an impact during World War II, replacing silk, which was controlled by the Japanese, in parachutes, and creating strong, lightweight, tow-ropes and tents.

After the war polyethene became iconic as Tupperware, and plastics became associated with everything that was modern. The range of applications is illustrated at the Tang by a list of nylon objects covering one wall of the exhibition space - from wigs to wall paper, and from violin strings to hair-curlers.

But the cultural problem with overabundance of plastics is not ignored. ’Plastic bags are a visible component of pollution in our everyday life,’ says Kara Daving, an artist based in Buffalo, New York. Daving is traveling to every state in the US capturing images of the ubiquitous trash. She has photographed polyethene bags snagged in cacti in the desert and caught in trees in northern New York, and four of her prints are included in this exhibition. ’This event has highlighted a whole other side of plastics for me - the physical and chemical aspects rather than their aesthetics,’ she says.

Personal molecules

’Six years ago I bought a DNA model and started working on a collage,’ says Michael Oatman: an artist who works in the architecture department at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York. ’I collected cutouts from science books, magazines, even menus and arranged them to track the path of the helices.’ The result is a comment on the central role of DNA, but it is also a ’personal molecule’ for Oatman - illustrating the journey of his own life.

Bryan Crockett’s work portrays actual mice engineered for the study of human disease. He suggests that through the manipulation of their DNA, these animals are predestined to the ’seven deadly sins’ - in this case anger, gluttony and sloth. His beautiful marble sculptures raise questions about morality in genetic engineering and the tension between science and religion.

DDT

The effects of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) on birds and animals, as highlighted by Rachel Carson’s iconic book, Silent Spring, sowed the first seeds of doubt in the public love affair with all things modern and chemical. Robert Dawson’s photograph shows White’s Point, near Santa Monica, California, US, where 200 tonnes of DDT was buried.

Social revolution

In Malissa Gwyn’s 1992 painting of progesterone, a female hormone associated with sex and pregnancy, the atoms are represented by fruits associated with desire - cherries, pears, apples. ’Fruit suggests beauty, transience, and decay,’ she says. ’I wanted the paintings to reveal correspondences between the molecule - the subject of my painting - and its relation to erotic appetite, and fragile human corporeality.’

The progestin molecule, a synthetic progestogen, was a key aspect of a social revolution in the 1960s and 1970s - the resurgence of feminism and women’s rights. Progestin is the active component of contraceptive pills that allow women to be sexually active without fear of pregnancy, and giving them the freedom to choose what they do with their own DNA. Chrissy Conant’s work is about that choice. Conant underwent hormone therapy to increase the number of eggs produced during ovulation. Her eggs were harvested and packaged in refrigerated glass tubes and jars as Chrissy Caviar? - the ultimate, consumable product. The procedure is the same as is used by women who donate their eggs to infertile couples (usually, in the US, for a fee). ’We all brand ourselves,’ comments Conant. ’In my case my brand is actually trademarked.’

Prozac (fluoxetine hydrochloride) was also selected based on its social impact. ’The 1980s was the hardest decade to assign,’ says Giguere. ’Many of our advisors proposed taxol, as there’s a fascinating history to its chemical synthesis.’ The decisive argument for fluoxetine hydrochloride came from the Skidmore students who had never heard of taxol.

Prozac was the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) used to treat depression, panic disorder, bulimia and obsessive compulsive disorders. Introduced in 1986 by Eli Lilly, it is the most widely prescribed antidepressant in history and is approved and marketed in more than 90 countries.

Fiona Case is a freelance science writer based in Vermont, US

The exhibition

Molecules That Matter will be at the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, US, until April 2008. It will open at the Chemical Heritage Foundation, Philadelphia, in August 2008, and will then travel to the College of Wooster, Ohio; Baylor University in Waco, Texas; and Grinnell College, Iowa in 2009.

Bucky balls and carbon nanotubes

No comments yet