Nina Notman takes a snapshot of the burgeoning field of health and fitness monitoring tattoos and patches

It’s long been known that body fluids are a window into the state of our health. The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, for example, would pour urine on the ground to see if it attracted insects, and if it did so the urinator would be diagnosed with boils. By the 19th century, specialised laboratories housing increasingly sophisticated diagnostic techniques for studying urine and blood samples had started to emerge. These labs remain the dominant model for body fluid diagnostics today but do, however, have one major disadvantage – speed. Samples must be collected, transported to the lab, and results waited for.

By the mid-20th century, faster alternatives started to be developed – body fluid diagnostic tests able to be conducted at patients’ bedsides or by the patients themselves. The urine dipstick came onto the market in the late 1950s, followed by portable glucose meters in 1970. These glucose meters revolutionised diabetic care, but the need for frequent finger pricking puts off patients.

The holy grail is real-time information obtained in a non-obtrusive manner

Amay Bandodkar, North Carolina State University, US

Flash glucose monitors, introduced in the mid-2010s, transformed diabetic care once again by reliving patients of the need to produce blood samples. Abbott’s Freestyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System is an electrochemical sensor that sits on the upper arm. It is a 35mm diameter electronics patch with a tiny wire that penetrates the skin to reach the interstitial fluid beneath it. The wire hosts immobilised glucose oxidase enzymes that oxidise glucose in the interstitial fluid, a biochemical event that is transduced into an electric current proportional in size to blood glucose concentration. The device only needs replacing every two weeks and readings are taken by holding a smartphone up to the patch.

‘The holy grail for diagnostics is devices [like flash glucose monitors] that give information on a real-time basis continuously in a non-obtrusive manner,’ says Amay Bandodkar, an expert in wearable sensors at North Carolina State University in the US. It’s more user-friendly and collects more data than any other approach, he adds.

Bandodkar and others are now working towards similar devices that sit on or just under the skin to collect information from body fluids that ranges from drug metabolite levels to hydration status to ultraviolet light (UV) exposure.

Blood analysing patches

Kevin Plaxco’s group at the University of California, Santa Barbara, US, is developing sensors analogous in design to the flash glucose sensor. The aim is to render therapeutic drug monitoring (measuring medication levels in blood to allow for dose adjustments) as convenient as the measurement of blood glucose levels is for diabetics.

‘The medical rationale for measuring drugs in the body is clear. Clinicians currently use poor, indirect predictors of metabolism to define drug doses,’ explains Plaxco. ‘We’re talking about slapping a device on someone’s arm, giving them a pill, and then measuring their specific metabolism in real time.’

Plaxco’s sensor has an electronics patch on the outside attached to a 3mm thin wire, placed into a vein near the skin’s surface. The outer patch is being developed by collaborators to closely replicate – in terms of both looks and functionality – the flash glucose monitor. Plaxco, meanwhile, is focused on the molecules that do the sensing. ‘That’s the bottleneck,’ he explains. ‘The electronics is pretty well established.’

His group are employing aptamers (short, single-stranded DNA molecules) as sensing molecules, rather than using enzymes as in the glucose system. This opens the technology up to a broader range of biological targets than just those with suitable enzymes, Plaxco says. ‘In theory, using aptamers we can make a recognition element against any water-soluble target.’ The aptamers are engineered so that they only fold when bound to its target. ‘We have developed an electrochemical method of monitoring that folding that then reports on the presence of the target,’ he says.

Drugs for which folding aptamers have already been designed include two chemotherapeutic agents and three antibiotics. For the antibiotics vancomycin and kanamycin, the researchers also – in rats – turned the sensor into a closed loop system where the information is inputted into a pump that then releases the required drug dosage. Plaxco says he is working with commercial partners to develop these sensors into prototypes suitable for clinical testing, but says there is no timeline for this yet.

Don’t sweat it

Sweat is another body fluid that holds a treasure-trove of information. ‘Sweat is attractive to us for the reason that you can capture it as it emerges from the pores in the surface of the skin, without any damage or penetration,’ explains John Rogers at Northwestern University in Illinois, US.

Sweat sensors are starting to make their way to market. The GX Sweat Patch, for example, determines hydration status and will hit the shelves later this year. This single-use patch is being manufactured by the spin-out company Epicore Biosystems (co-founded by Rogers), in collaboration with Gatorade, a US sports drink brand.

The Gatorade patch has inlets in contact with the skin that direct sweat into microfluidic channels. ‘Sweat glands are pumps that push the sweat outside of the body,’ explains Bandodkar. The patch is designed so that the natural pressure at which sweat droplets are pumped out is sufficient to direct the fluid inside the channels.

The patch has two channels: a snaking one for measuring sweat rate and a straight one for chloride ion loss. For sweat rate, the channel contains a colorimetric indicator that changes colour when chelated with water – how far along the path from the inlets that the colour change has occurred provides quantitative information on the wearer’s sweat rate. The second channel has an indicator that complexes with chloride ions to give a distinct colour. A smartphone app analyses the colour changes and informs the wearer what Gatorade drink will optimise their hydration during exercise. ‘I think [the patch] will be embraced by hardcore athletes who are interested in gaining that little edge over the competition,’ says Rogers.

Power it up

Rogers and his collaborator Bandodkar have developed a modified version of this device with an additional electrochemical component that enables the colour-change reactions to be analysed more accurately than by the naked eye or smartphone camera alone. These more precise measurements open up applications beyond fitness monitoring such as critical patient monitoring, explains Bandodkar.

The tattoo is just the sensing interface

Francesco Greco, Graz University of Technology, Austria

A significant challenge for this hybrid device design was how to power the process of transmitting the electrochemical data to a smartphone without the need for a bulky battery. The team took inspiration from biofuel cells to develop a self-powered system. ‘Enzymatic reactions spontaneously produce voltage signals proportional to the biomarker concentration present in the sweat which can be easily captured and wirelessly transmitted in a battery-free fashion to the wearer’s smartphone via nearfield communication technology – this is the same wireless technology that is used to wirelessly power smartphones,’ Bandodkar explains.

These hybrid patches have two layers – a lower, disposable microfluidic module and a reusable electronic module that sits on top. These patches are currently being trialled as a lightweight alternative to current sweat test apparatus used for cystic fibrosis diagnosis in newborns. People with cystic fibrosis have more chloride in their sweat than those without.

Nutrition is the key

Joseph Wang and his group at the University of California, San Diego, in the US are also developing hybrid microfluidic and electrochemical patches for sweat monitoring. These devices – like Roger’s – have a disposable microfluidic component and a reusable, flexible electronic sections. But they don’t use a colour-changing reaction and instead monitor the oxidation of glucose and other species by enzymes. They also require a battery.

Wang is also making an alternative version of the disposable component, where the relevant enzyme is immobilised onto a sensor printed on dissolvable starch/dextrin paper. Oxidation by the enzymes generates an electric current that correlates in strength with the amount of the relevant analyte in the blood.

The dissolvable paper for these devices is the same material used in the temporary tattoos loved by kids the world over; they are applied by placing against the skin and wetting to dissolve the starch/dextrin component and activate the adhesive. Temporary tattoo-delivered sensors are even more flexible, lighter weight and cheaper to produce than the microfluidic ones, Wang explains. Prototypes created so far include those with alcohol oxidases, for detecting alcohol levels, and ascorbate oxidases, for monitoring vitamin C.

These sensors also have an inbuilt tool for inducing sweat, as unlike the microfluidic sensors they are not designed for use during exercise. This tool is two graphite ink (with dispersed rhodium particles) electrodes, with a small amount of the sweat-simulating drug pilocarpine on the anode. When the electronics module passes a small electric current through the electrodes, pilocarpine is delivered into the skin.

The vitamin C sensor is being developed in collaboration with DSM Nutritional Products in Switzerland. Other vitamins can probably also be monitored by immobilising different enzymes in the same device, says Wang. ‘This is a move towards personalised nutrition.’ No timeline to market has been revealed yet for these sensors.

Soaking up the sun

LogicInk, in San Francisco, US, is another entity developing temporary tattoo-delivered sensors. The company is tight-lipped about the science behind its sensors, apart from revealing that the sensing molecules being employed in its sensors include DNA nanoparticles. ‘Not all sensors that we are working on involve DNA nanotechnology but, in general, this is a big area of focus for us,’ explains LogicInk founder Carlos Olguin. His academic collaborators include Hendrik Dietz, a DNA nanotechnologist at the Technical University of Munich in Germany.

In summer 2020, LogicInk soft launched its first tattoo – a UV sensor that monitors cumulative UV exposure. Initially dark blue, the tattoo turns bright pink when the wearer’s daily exposure has reached the level set by the World Health Organization for sensitive skin. This means it will turn pink just before your skin does.

An air pollution (PM2.5) sensor of a similar design has been prototyped and one that provides information from sweat is being worked on. ‘Sensors directly interfacing with your skin and changing shape or colour to alert you of conditions of interest in your body, like hydration levels, is something we’re currently working with,’ says Olguin.

Feeling electric

Temporary tattoo-delivered devices can also be used for collecting electrophysiological information from the body. Francesco Greco’s group at Graz University of Technology in Austria has pioneered this concept for producing ultra thin electrodes for wiring patients up to electrophysiological instruments.

The group inkjet print conductive polymer electrodes onto the dissolvable paper, as a direct replacement for the bulky electrodes typically used today. ‘The tattoo is just the sensing interface. The processing, acquisition and transmission of data is made through the usual hardware used in the hospital,’ Greco explains.

The advantages of these electrodes over the status quo include comfort and functionality. ‘When you place a rigid metal electrode on top of the skin, the actual contact area is low. There is a stiffness problem,’ Greco says. For this reason, a gel is often applied to the electrodes but this dries out after a short time. By comparison, he explains, the new electrodes electrodes are ultra-thin (under 1µm), highly flexible and fit snugly against the skin’s surface making them both more comfortable and more accurate. Measurement quality is also boosted by the fact the conducting polymer ink is a mixed conductor, he adds. ‘It behaves dually, as an electronic conductor and ionic conductor.’

Electrophysiological techniques the electrodes have been tested with so far include electromyography (to evaluate muscle electrical activity from muscles), electrocardiography (for heart electrical activity) and electroencephalography (for brain electrical activity). Greco says that they are in conversations with companies about commercialising these electrodes. He is also collaborating with Graz-based designers of brain–computer interfaces to assess the use of the electrodes in devices that allow people to interact with computers using brain activity alone.

Going under the skin

But what if instead of replacing clunky sensing tools with ones that you can barely feel against the skin, you went one step further and placed the sensors under the skin instead? Two research groups are now started to explore this idea. These both take inspiration from traditional tattoos where pigment particles are injected under the skin using a tattoo gun.

‘We are making functional microscopic implants that go in the dermis and confer some functional or health benefits,’ explains Carson Bruns, a nanomaterials professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, US. He has developed a functional tattoo containing UV sensing molecular machines encased in plastic shells, which are injected into the dermis for monitoring UV exposure.

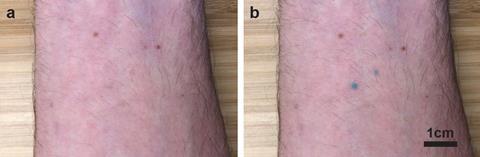

The UV sensing molecule is ‘a molecular switch that, when it absorbs a UV photon, undergoes a structural change that makes it turn from colourless to blue’, says Bruns. ‘The more UV light there is, the more blue the tattoo becomes.’ A smartphone photo and algorithm quantifies the exposure and, once the UV light levels have diminished again, the molecules will switch back to their colourless state. So far, these functional tattoos have been tested on ex vivo pig skin and also on Bruns himself. ‘We have a grant to test these in a live rodent model, so we’re going to be doing that this year,’ he adds.

It’ll take 10–20 years for smart tattoos to be approved for use

Ali Yetisen, Imperial College London, UK

Meanwhile, Ali Yetisen at Imperial College London, UK, is focused on functional tattoos that monitor conditions inside the body such as glucose levels and hydration status. ‘We have created a line of compounds that can be directly tattooed inside skin and interact with biomarkers in the interstitial fluid or extracellular matrix to provide quantitative information about condition of the body,’ he says.

The glucose sensing tattoo is multi-component. First, glucose oxidase oxidises the glucose to form hydrogen peroxide, this then oxidises tetramethylbenzidine (with the help of the enzyme peroxidise) to form a blue–green molecule. This colour change is visible to the naked eye, with a smartphone algorithm providing quantitative information.

The hydration sensor, however, doesn’t trigger a visible change; it fluoresces in response to electrolytes. Crown ethers (cyclic compounds containing several ether groups) that fluoresce when they chelate with certain ions are the sensing molecules. Three distinct crown ethers are included in each sensor – ones that capture protons (giving pH information), sodium and potassium ions. These tattoos require a portable device with optical filters to enable a smartphone to readout the information.

Neither Burns nor Yetisen expect their functional inks to be available in your local tattoo parlour or pharmacy anytime soon. It’ll take 10 to 20 years to develop these and get them approved for use, says Yetisen. But by then, most researchers do expect that sensing devices affixed to the surface of the skin will be as common place as Fitbits and Apple Watches are today and will be providing us with an almost unimaginably deep insight into the workings of our bodies.

Nina Notman is a science writer based in Salisbury, UK

No comments yet