As consumers turn their backs on artificial food colorants, food scientists learn how to work with natural alternatives. Sarah Houlton investigates

It’s nearly a decade since a study carried out by UK scientists at the University of Southampton linked a handful of artificial food colours with hyperactivity in children. The six colours – allura red, carmoisine, ponceau 4R, quinoline yellow WS, sunset yellow and tartrazine – require the label declaration ‘may have an adverse effect on activity and attention in children’ in Europe. Consumer demand means very few food products in Europe now contain them. In the UK, the most familiar are Irn-Bru and original Lucozade, which both still contain sunset yellow and ponceau 4R.

The wholesale reformulation of hundreds of food products that used to contain one or more of these six synthetic colours has led to a rapid rise in the usage of ‘natural’ colours. ‘Europe is leading the consumer drive to get more naturals, with companies looking to replace any artificial colours,’ explains Persis Subramaniam, head of product development for the food innovation group at Leatherhead Food Research, UK. ‘It started with Southampton, but there is a wider interest in natural products in general now, looking for store cupboard, back-to-nature ingredients as opposed to highly processed ones.’

The US is a long way behind. Take those brightly coloured sweets, Skittles. If you buy a bag in the UK, the ingredient listing mostly comprises natural colours, with the exception of indigo carmine and brilliant blue, neither of which was implicated in the Southampton study. Buy what is, ostensibly, the same bag of sweets in the US (albeit with grape-flavoured purple ones rather than the much nicer blackcurrant), and those natural colours are conspicuous by their absence from the product label. In their place are sunset yellow, tartrazine and allura red.

‘More than 90% of all European new product launches in the past four years have used natural colours,’ says Roland Beck, managing director of the colorant manufacturing firm Sensient Food Colors Europe in Geesthacht, Germany. ‘In North America, the figure is closer to a half – and even lower if Canada is taken out of the equation.’

Colour challenges

From a chemistry point of view, there is nothing better than synthetic colours, Beck says. ‘They are incredibly stable, water soluble and you can use them in any application at any temperature and the colour shade will not change.’ In contrast, natural colours present all manner of technical problems for food producers – solubility, pH, temperature, light and air can all affect the colour and how it behaves.

Each individual natural colour pigment produces its own formulation challenge. For example, some are water soluble and some oil soluble. ‘Most food products are fairly water-rich, so to use an oil-soluble pigment you need to convert it into a form that is compatible with an aqueous environment,’ Beck says. ‘This is done by emulsification, or dispersion followed by stabilisation of the dispersion.’

Choosing the right emulsifying system for an oil-soluble pigment is important. ‘You can’t use a sucrose ester emulsified beta-carotene in a typical low pH beverage as it is unstable below pH 4,’ Beck says. ‘The emulsion will break down, giving a ring of coloured oil on the neck of the bottle. As colouring ingredient formulations are application-specific, many different ones are required. With sunset yellow, you buy a single solution that you can use in any application. But for beta-carotene, you will need five or six different versions.’

To complicate matters further for global food companies, there is no harmonised international colour legislation, and a food product that’s perfectly fine in one country may not be allowed elsewhere. ‘In [EU] legislation, natural flavours are described, but there is no legal definition,’ says Oliver Leedam, senior regulatory advisor at Leatherhead Food Research. In contrast, all colours are considered artificial in the US, as the colour of the foodstuff is being changed. ‘There, each batch has to be tested and certified as meeting the standards,’ he adds. Various colours are permitted in Europe that are not in the US, and vice versa.

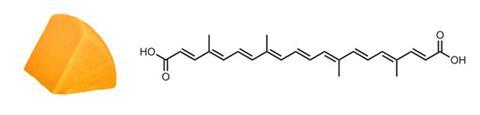

Carotenoids

Carotenoids are familiar on food ingredient listings, with the list including substances such as beta-carotene, apocarotenal, lycopene, annatto, paprika and lutein. They can deliver shades from weak yellow to a reddish colour, and anything in between. ‘Beta-carotene can deliver weak yellow to a reddish-orange hue, and apocarotenal gives a very deep orange colour,’ says Jan Holm-Hansen, managing director of the carotenoids producer Allied Biotech Europe, in Karlsruhe, Germany. ‘Pure beta-carotene oxidises rapidly and is not water soluble – and only slightly soluble in oil. But via nanotechnology it can be encapsulated and made soluble, so it can be used in products like juices and dairy products. You can also alter the trans ratio to have an impact on the colour.’

Physics is almost more important than chemistry with carotenoids, Beck says. ‘The shade you get from beta-carotene depends on what you do with it,’ he says. ‘If you make a true emulsion, it is yellow, but if you make a dispersion it is orange, and if it is crystallised in a certain way the colour is more red, like watermelon.’

Carotenoids will often be produced synthetically, or semi-synthetically, but are the same molecules found in nature. ‘Some people will say that this makes them artificial, but if it’s in the natural box of colours, it is exactly the same as in nature,’ Holm-Hansen says.

They all decay by oxidation, losing their colour, so incorporating antioxidant ingredients is the key to stability and a good shelf-life in the warehouse, during processing and over time on the supermarket shelf. This is commonly done with ascorbic acid, ascorbyl palmitate or tocopherol.

Temperature, pH, air and light are also important. ‘Food production often includes heat treatment to control bacteria, which can affect the colour,’ Holm-Hansen says. ‘Transparent packaging makes them subject to daylight, so for good shelf-life the carotenoid must be made more stable to light. We protect the molecules by encapsulating them in a starch or gum Arabic.’

Another carotenoid ingredient, oleoresin paprika, is commonly supplied on a carrier such as salt, and the colour might last only four to six weeks, says Carol Locey, natural colours product director at Kalamazoo, US-based Kalsec. This natural food additives company has managed to formulate a paprika that retains its colour for two or three years. ‘We have to select the best lot of material to extract, and then combine it with natural antioxidants such as rosemary extract to enhance its stability.’

Orange-red annatto is derived from the seeds of the South American achiote tree, Bixa orellana. The main coloured component is the oil-soluble carotenoid bixin, Locey says, which has a carboxylic acid group at one end of the conjugated chain, and a methyl ester at the other. Norbixin is the de-esterified diacid, which is water soluble. It’s in widespread use in dairy products such as cheddar, colby and red leicester cheeses, where it has been used for centuries to impart a characteristic orange colour.

Canthaxanthin, meanwhile, produces a bright deep red colour and, while it is permitted in the US, that’s not the case in Europe. It has an E-number, but the only permitted food use is the strasbourg sausage. The restriction arises from a health scare in the late 1980s, when people taking canthaxanthin capsules as a sun-tanning aid developed reversible deposits of canthaxanthin crystals in their retinas. Clearly the amount they had taken was orders of magnitude greater than would ever be consumed as a food colorant, but the resulting EU review led to its almost total ban.

Water-soluble pigments

The largest group of water-soluble pigments is the anthocyanins, whose colour tends to change with pH. ‘They’re basically indicators,’ Beck says. ‘An anthocyanin can be anywhere from very red to a purple to blueish at neutral pH, and if you increase the pH further it will go green or brown, and ultimately colourless. This pH sensitivity makes food applications a real challenge.’

This is one of the biggest differences between natural and synthetic colours – synthetic colours remain a constant shade regardless of pH. Anthocyanins are also often light sensitive. In contrast to the carotenoids, which need ascorbic acid to stabilise them, they will be destroyed by ascorbic acid. ‘You can’t make an orange by combining a yellow beta-carotene emulsion with a red anthocyanin product because either there is too much ascorbic acid and the anthocyanin will be destroyed, or not enough and the beta-carotene is destroyed,’ says Beck.

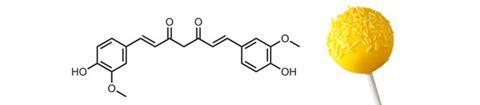

Another water-soluble pigment, curcumin, is extracted from turmeric. Its vibrant lemon-yellow colouration fades very rapidly in beverages as it is not light stable. ‘The combination of light and free water drives the degradation,’ explains Andrew Kendrick, natural colours applications manager at FMC in Burton-on-Trent, UK. ‘Yellow sweets are commonly coloured with curcumin, and it performs brilliantly in confectionery, with a fantastic shelf-life and maintaining its vibrancy. But in a beverage or anywhere else with an excess of free water, it will fade very rapidly. You always have to choose the right pigment for the application.’

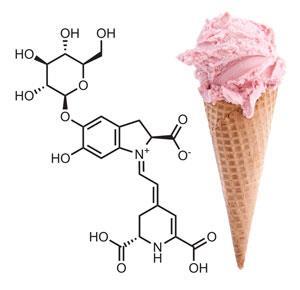

One natural pigment that many food manufacturers are moving away from is carmine, which, as it is derived from the cochineal beetle, is not vegetarian, kosher or halal. Carmine is a very stable red, and while anthocyanins are a successful replacement in beverages, this is not the case for neutral applications. Here, the colour of choice is often one derived from beetroot, which contains the indole-based pigment betanin. ‘Beetroot used for commercial colour production are selectively bred to contain more betanin,’ Kendrick says. The main drawback with beetroot is that it goes brown on heating.

Ice cream is the ideal matrix for natural colours, being stored frozen in the dark, which prevents browning. Strawberry ice cream is almost always coloured with beetroot in Europe nowadays. Products that are heated during manufacture pose more of a problem. ‘To replace carmine in applications such as marshmallows, pink wafer biscuits and lollipops, colour companies and food producers worked together to determine where in the process the colour was being lost,’ adds Kendrick. ‘Solutions could include changing the heating cycle, introducing active cooling or putting the final product on trays to cool rather than in a hopper.’

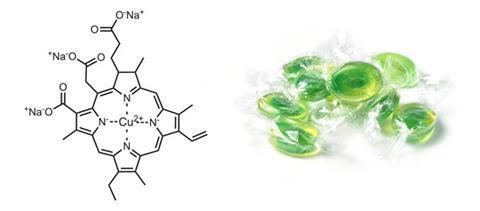

Greens and blues

Green can be achieved using chlorophyll and copper chlorophyllin, a more stable derivative of chlorophyll with a more vibrant blue-green shade, and a more lime-green shade is possible when mixed with curcumin. It’s not acid stable, but with clever formulation can be stabilised in an acidic beverage for a long time, Kendrick says.

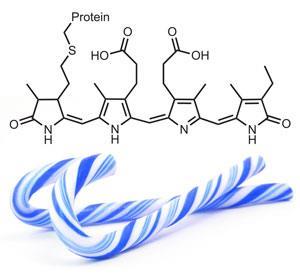

Blue is difficult to achieve with natural colours, and the only real option is spirulina blue, concentrated from spirulina blue–green algae. ‘The colouring portion is phycocyanin, which is a pigment–protein complex,’ Beck says. ‘Its proteinaceous nature means it’s limited to pH neutral applications such as hard candy shells. It’s not a pure chromophore, and often contains a small amount of a reddish phycorubin component that can lend brown undertones when used with yellow to make a green.’

In the US, chlorophyll and copper chlorophyllin are not permitted, but spirulina is. ‘The FDA is still considering the petition for copper chlorophyllin, so green often involves spirulina mixed with curcumin,’ Kendrick says. ‘Stability is often a problem, as spirulina is not particularly heat stable.’

Colouring foods

In contrast to a colour additive isolated from a natural source, a colouring food that is a whole extract of the original material does not have to be declared as an added colour on the label, just as an ingredient.

A set of guidance notes from the EU came into effect in November 2015, classifying food extracts with colouring properties. As well as beetroot, examples include black carrot, strawberry skins, radishes, safflower, spinach and tomatoes. ‘As long as you don’t change the ratio between the colour and the rest of the material as you concentrate it, it doesn’t become a colour ingredient,’ Leedam says. ‘But if you start selectively extracting the colour, it needs an E-number and to go through the full additive registration procedure.’

‘Colouring foods are increasingly popular in confectionery,’ Kendrick adds. ‘The challenge is to deliver a stable, vibrant product starting from something that hasn’t been purified as much as a colour ingredient. Increasingly, our customers are asking for colouring food options.’

Changing food products

Introducing a brand new food product using natural colours is one thing. Reformulating existing ones, where consumers know and love what they buy, is another entirely. A shift to natural colours often means a subtle – or not so subtle – change in colour. ‘Sometimes the shade isn’t going to be as bright,’ Locey says. ‘Bright yellows can be done, but day-glo orange can’t. Super-bright reds and purples are difficult, too.’ And in the US, where brightly coloured processed foods are commonplace, reproducing certain colours is a real challenge.

The momentum to change is building up, however, and products that manufacturers in the past might have said there was no way they would change are now being reformulated. ‘The US is catching up,’ Locey says. ‘As in the EU, it is consumer-led, and companies are definitely on the path to convert as much product as they can to natural colours. People are excited when I tell them I sell colours made from carrots.’

As FMC’s Kendrick says, moving from a synthetic colour that is stable and works anywhere to natural colours that all have their own characteristics is a fascinating challenge. ‘It’s very rewarding to walk around the supermarket and see products you worked on that are stable,’ he says. ‘People don’t realise the complexity of making it work.’

Sarah Houlton is a science writer based in Boston, US

No comments yet