Mining companies are exploring underwater volcanic vents, hoping to extract metals such as gold and copper. Victoria Gill looks at the technical, environmental and political hurdles

When marine biologist Samantha Smith told colleagues that she was going to work for a sea floor mining company, they thought she had crossed over to the dark side.

Indeed, while Smith was an academic working at the University of Toronto, Canada, she also had serious reservations about the environmental consequences of extracting metals such as gold, silver and copper from ocean bed deposits.

’I wasn’t sure I would ever agree with it,’ she smiles. Now, her view has fundamentally changed, and so has her career. She has moved from Canada to Australia to work for Nautilus Minerals, a mining company which is conducting what has been hailed as pioneering work in this emerging industry. It aims to be the first company to commercially extract minerals from the sea floor.

Smith initially worked as an independent scientific consultant during Nautilus’ exploratory drilling programme in 2005, in the Manus Basin off the east coast of Papua New Guinea, where copper sulfide and gold deposits had been discovered 1600 metres below sea level. Involvement in this project gave Smith a deeper insight into the potential of sea floor mining, which ultimately convinced her to join the company. Smith is now coordinating the environmental impact assessment the company needs before it can start to mine the area.

Mineral water

Although it’s not a new idea, mining from the seabed is controversial, both environmentally and commercially. In the 1970s and 80s, several of the world’s largest mining companies, including Kenecott, Inco and Pruesag Hughes, along with government agencies, invested in programmes to mine polymetallic manganese nodules from the sea floor. For the most part, the rush of interest ended in failure as collecting these tiny but metal-rich lumps, formed over millions of years by the precipitation of metals from seawater, proved unprofitable. This expensive failure led most of the mining industry to stick to dry land. But interest has been rekindled by the discovery of rich mineral deposits around hydrothermal vents.

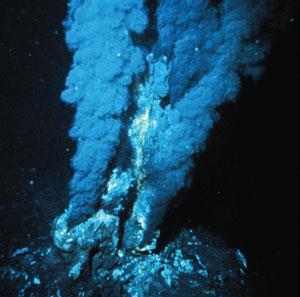

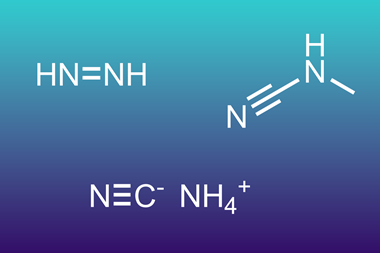

These underwater volcanic sites are mostly found in areas known as deep sea spreading centres, where tectonic plates are constantly moving apart and new sea floor is formed by the magma thrown up in frequent eruptions. As the plates pull apart, deep fractures develop and seawater seeps in. The water is then super-heated by magma and reacts with metals and other elements in the hot rock. This heated water, now very buoyant, rushes back up to the sea floor where the dissolved minerals are precipitated by the turbulent mixing with cold seawater. The minerals, like flurries of dark snow, form drifts that grow into chimneys - dubbed ’black smokers’ - around the vents. Since their discovery in 1977 during a geological expedition to the Galapagos Rift, off the coast of South America, biologists and biochemists have joined geologists in their exploration of these dynamic sites.

Chuck Fisher, a marine biologist from Pennsylvania State University, University Park, US, is studying the abundance of life around black smokers. ’Hydrothermal vents are extreme environments,’ he says. ’The exchanges between chemicals, bacteria and animals at these severe temperature gradients and high pressures represent a unique mode of life.’

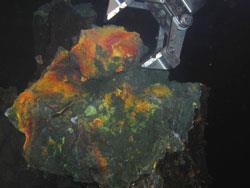

The discovery of polymetallic sulfide deposits littered around black smokers was a lucky consequence of this sudden interest in hydrothermal vents. Deposits are produced when the chimneys collapse, leaving mounds of sulfide debris. Hydrothermal fluid circulating within the mound helps to dissolve and recrystallise the minerals, enriching the metal content of the rubble.

Steve Scott, an emeritus professor of mining geology at the University of Toronto, has been talking about the possibility of mining these deposits for a long time. In 1982, he was one of the first geologists to explore black smokers that had recently been found at a depth of two kilometres in the Gulf of California, off the coast of Mexico. He also discovered the deposits at the Papua New Guinea site that Nautilus is now exploring. ’Deposits that have been found there so far are around five to seven million tonnes,’ says Scott. ’That’s not huge but it’s very encouraging. And the deposits that we find here are a much higher grade than you would usually find on land.’

Venting anger

About 350 vent fields have been discovered in the world’s oceans so far, and there is growing commercial interest and investment in exploration of sites that continue to bear metallic fruit.

But there is concern from many environmental campaigners and marine biologists that the unusual ecosystems around these sites might be destroyed by mining, as has happened so often on dry land. ’These sites have limited physical integrity and great biodiversity,’ says Simon Cripps, director of the WWF’s global marine programme.

The WWF has a long-standing campaign to protect sensitive areas of marine life from damage by mining and dredging. ’We would like to see a thorough, independent impact assessment before any mining work begins,’ says Cripps.

’There is only interest in mining old, dead vents where deposits have been left behind,’ responds Scott. ’It is impossible to mine active vents, as the water temperature can reach 400?C. This would simply destroy mining equipment. Clearly, though, there is still some biodiversity at these sites that needs to be looked into.’

One way to prevent the over-exploitation of hydrothermal vents would be to maintain some sites as marine protected areas (MPAs), similar to sites of special scientific interest on land, suggests Scott. But opponents also point out that mining vessels, designed to extract pure metals from their ores, will also carry thousands of tonnes of sulfurous waste that could cause potentially devastating acidification if dumped back into the sea, whether deliberately or accidentally.

Footprints on the seabed

To address these concerns, Nautilus is financing a large-scale, independent environmental impact assessment which it will present to the Papua New Guinea government this month, as part of their first mining licence application.

The assessment is led by Smith, recently converted to the cause of underwater mining. ’Environmentally, sea floor mining is a better alternative to terrestrial mining,’ she argues. ’Mining on land leaves a substantial footprint. It leaves polluted waterways, carbon emissions from heavy machinery and millions of tonnes of waste rock that has to be dumped somewhere.’

David Heydon, Nautilus’ chief executive, agrees. ’Land is rare. It’s only 30 per cent of our planet,’ he says. ’We only have a few Andes mountains, but they are home to several copper mines. Shouldn’t we protect these areas, since they are where we have to live?’

’We have found underwater deposits that are about 10 per cent copper compared to 1 per cent on land, which means that much smaller deposits can be mined profitably,’ says Heydon. ’When you mine on land you either have to dig a shaft or strip off all of the surface material. Everything you strip off or dig out is waste so, for example, with a 20 million tonne deposit of one per cent copper in the Andes, you would need to cut open the mountain and take out 80 million tonnes of rock. 60 million of that will be waste rock which has to be put into the valley. But with mining from the sea floor, you’re essentially cutting a lump of deposit from the seabed, so there’s no shaft and little waste rock,’ he says.

So why aren’t other companies lining up to join the race to the deep? ’Twenty years ago, most mining companies didn’t want to hear about this possibility. They thought it was too difficult,’ says Scott. ’Now, some of them are starting to recognise that it might be easier to go through a few thousand metres of water than it is to go though a few thousand metres of rock.’

So far, no commercial extractions have taken place, and Nautilus’ investment has yet to be tested. ’At the moment, we don’t have a mining licence from the Papua New Guinea government. This will be subject to our environmental impact assessment,’ says Heydon. ’We’re still exploring, but we hope to be in production at the site by the end of 2009.’

10,000 leagues under the sea

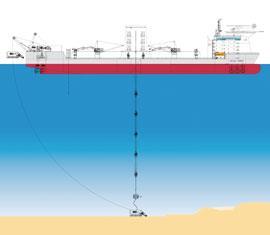

Nautilus estimates that the start-up costs for large scale sea floor mining could be as high as $300 million (?152 million). The company has already invested heavily in exploration and recently signed a deal with the Belgian dredging company Jan de Nul, which is contributing €100 million (?67 million) to build a specialised surface vessel, Jules Verne.

Nautilus will contribute $120 million to develop undersea tools, including pumps, pipes and two subsea crawler-miners. It will also partner with a group of engineering companies with expertise in drilling and geophysics. If Jules Verne is in place by 2009, it could stay at the Papua New Guinea site until 2014, before moving on to exploit other deposits. Nautilus estimates that it will be able to mine 6000 tonnes a day from its target site.

Although there are technological hurdles to be overcome, O’Sullivan says that ’the technology already exists; it just hasn’t been integrated in this way. One beauty of the sea floor model is that a floating equipment production chain is our one main investment. Once we have the chain we can easily bring it up and redeploy it to another area.’

Off-shore oil drilling technology already reaches the depths at which they need to mine. And sea floor mining is not without precedent. South African diamond giant De Beers has been gathering diamonds from a depth of a few hundred metres off the coast of South Africa and Namibia since the 1990s, with custom-built tracked mining vehicles for that purpose. For metallic mineral extraction, Nautilus simply needs to add a cutter head to a similar vehicle and develop a pump to bring the resulting slurry to the surface.

This mixture of solids and water can be separated by filtration or blasting with air. The pure metal is then extracted in the same way as terrestrial mining, using surfactants to float waste materials away from the pure minerals, which can then be smelted into metal.

Another important player in undersea mining is Neptune Minerals, based in Sydney, Australia, which says that it should be ready to progress to offshore extraction in the next five years. Neptune is exploring for mineral deposits off northern New Zealand, hunting for copper, silver, zinc, lead and gold on the Kermadec sea mounts, which were created by hydrothermal plumes.

Neptune started drilling seabed cores, to test the commercial suitability of the site, in December 2005. Other mining companies are waiting to see how well Nautilus and Neptune fare before taking the plunge themselves.

Friends in wet places

Nautilus has also created an important alliance with the marine research community, by conducting exploratory work with independent scientists. For example, they used the research ship Melville, operated by the Scripps Institute in La Jolla, California, to deploy a robotic sub that could collect sea floor samples.

This provides research funding for a community whose work is particularly expensive. ’It’s a great opportunity for academic and industrial collaboration,’ says Smith. ’I’ve been interested in deep sea research for a long time and I recognise that here we have a chance to conduct studies to parts of the sea floor that will make them some of the best studied sea floor areas in the world.’ Clearly, it also helps to have as many marine biologists on board as possible.

The WWF remains sceptical. ’It isn’t a useful argument to say that this is less harmful than mining on land, since terrestrial mining is already extremely harmful,’ says Cripps. ’Making such a comparison is a counter-productive argument. What we’re interested in is seeing a thorough assessment of the real impact that this will have.’

But for underwater prospectors, technological and environmental issues could be less significant than political stumbling blocks. The United Nations Convention of the law of the sea is supposed to offer clear guidance in seabed prospecting claims, yet Canada, Denmark and Russia are currently fighting to prove that they should have control of the same underwater mountain ridge in the Arctic, thought to contain substantial mineral and gas reserves.

The International Seabed Authority, established by the convention in 1994, is currently formulating regulations to govern mineral prospecting in international waters. It hopes to even out the political bumps before commercial interest in the sea floor builds up.

Meanwhile, the areas being explored by Neptune and Nautilus are controlled by the only two countries that already have legislation to manage offshore mining. The governments of Papua New Guinea and New Zealand expect a fixed percentage of the companies’ profits in return for their cooperation.

Clearer regulation may encourage other mining companies to start exploring the seas. And the recent surge in metal prices has boosted investment for sea floor mining, says Simon McDonald, chief executive of Neptune. ’It has made it much easier for us to raise money.’

The demands of the market could ultimately make seabed mining an inevitability, says Scott, because there will always be a growing and inescapable need for more metals. ’If you can’t grow it, you have to mine it,’ he says.

Show me the money

The growing demand for metals is a global concern which has been accelerated by emerging economies. China’s share of world metal consumption has leapt from under 10 per cent to around 25 per cent in the past decade, according to a recent report by The Economist. And growing demand is keeping prices high. ’China needs to house 30 million more people every year, and the average house needs 100 kg of copper,’ says Nautilus’ David Heydon. ’In India, many people have the modest desire to have a tin roof for their houses, made from galvanised steel, which contains a lot of zinc. It’s those who can least afford it who are suffering from these high prices.’

The United Nations convention on the law of the sea (UNCLOS) declares that 60 per cent of the world’s oceans are classed as international waters. In theory, this means that their resources are not the exclusive property of any one country and should be used for the good of mankind. Heydon thinks that sea floor mining has a role to play in sharing out some of the sea’s spoils.

No comments yet