In 2013, nine years after Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov first isolated graphene using a piece of sticky tape and three years after they won the Nobel prize in physics for their discovery, a €1 billion (£870 million), 10-year project was launched to help push graphene to the forefront of European scientific research.

Funded by the European Commission and EU member states, the Graphene Flagship aimed to take graphene out of the laboratory and onto the market in the form of faster and more reliable optic and electronic devices, longer-lasting batteries and more environmentally-friendly construction materials.

Its anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on the flagship and what it has achieved, although the full impact of the programme may not be felt for some time, says Jari Kinaret, who directed the flagship for 10 years. ‘There are academic studies that look into the impact of publicly funded research initiatives, and they estimate that the impact can really only be measured 10 or 15 years after the project has ended,’ he says.

The 10-year mark also signals the start of a new phase of the project as many of the flagship’s activities will now come under Horizon Europe. The first projects were announced in March 2023, but further projects will be selected later this year and in 2024.

What the flagship will look like in future and whether the collaborations it has enabled over the years will continue is still a work in progress. However, what is certain is that the progress propelled by the flagship is here to stay, with graphene now playing a role in many of our day-to-day lives.

‘When we started, there were very few companies in Europe that were in any way involved in graphene,’ explains Kinaret. ‘Now 50% of our 172 partners are companies either large or small.

‘You can almost certainly take a 15-minute walk from your office and buy actual commercial products that have graphene in them, you may already have products without knowing.’

Flagship success

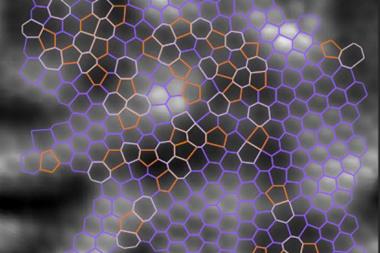

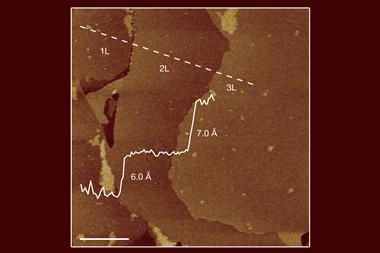

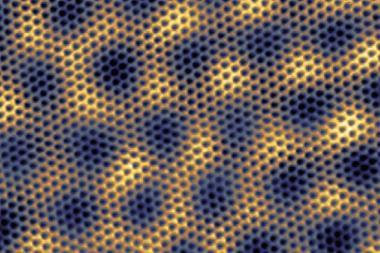

Since 2013, the Graphene Flagship has grown from a primarily academic project working on a single material to an increasingly industry-focused project concentrating on market applications of a whole family of two-dimensional and layered materials. ‘The project is called the Graphene Flagship, but really if we were to be accurate, we should call it the “Graphene and related 2D Materials Flagship” – but that is too much of a mouthful,’ Kinaret notes.

Kinaret says that the flagship has performed ‘extremely well’ against the goals it was set at the start. The target for papers in top journals was 25 publications per €10 million of funding and one patent application per €10 million of funding. ‘When it comes to patent applications, we beat [the commission’s] target by a factor between 13 and 14, so it’s not like we are just 10% better than the target, we are 13 times better. When it comes to scientific publications, we are about seven times better than the target,’ says Kinaret. However, an unofficial target, he says, has been the number of spin-off companies that have subsequently been created, of which there are at least 17.

Andrea Ferrari, science and technology officer for the flagship and director of the Cambridge Graphene Centre, says the flagship is one of, if not the, most successful European project that the commission has ever sponsored. He highlights that, based on a total investment of €1.4 billion in European projects for graphene and related materials, the Graphene Flagship generated €5.9 billion and helped to create 81,622 jobs.

‘The reason for this [success] is quite straightforward,’ he says. ‘It has been an initiative that is going on [and] has been going on now for at least 10 years, which means people were in it for the long run. This ability to think with long term in mind, not short term, was able to leverage a lot of work.’

Graphene in action

Airbus has been a Graphene Flagship partner from the beginning. ‘The promise [of graphene] was many-fold,’ says Elmar Bonaccurso, senior scientist at Airbus. ‘We are always looking for lightweight materials to make aerostructures so the promises were that graphene could really have an impact there.’

One area graphene has delivered in is in surface technologies for aviation. ‘On helicopters and large passenger aircraft we are always in need of coatings that are more resistant to environmental situations like UV radiation, rain erosion, so we don’t have to replace the coating or maintain the coating as often,’ says Bonaccurso.

For Bonaccurso the flagship has had huge benefits because it brought together more than 800 researchers that Airbus could collaborate with. This collaboration led to the launch of a graphene-based thermoelectric ice protection system in 2020 to investigate the use of graphene as a flexible, low power, low weight heating system to protect aircraft from ice formation.

‘Nowadays, state-of-the-art ice protection system are working very well but they are bulky, and heavy. They can’t be adapted so easily to new types of structures and upcoming urban air mobility so we cannot adapt them so easily,’ Bonaccurso says.

Graphenea, a graphene producer founded in 2010, is another company that has been with the flagship from the very start. Amaia Zurutuza, a polymer chemist and chief scientific officer of the company, recalls hearing the initial conversations about the flagship. ‘At the beginning of 2011 we found out about some meetings that were taking place in relation to graphene and graphene research. We were the second company to be approached [to be involved] after Nokia because we were unique as a European company producing graphene.’

Over the past 10 years, Graphenea has grown from a team of four to one of 40. Zurutuza says the flagship has helped the company to improve the materials it produces and learn about the integration of graphene into the semiconductor industry. ‘It has been really amazing for us and I think we got where we got thanks to the flagship and all the collaborations we had in there – it has helped to build an ecosystem in Europe around graphene and 2D materials.’

Looking to the future

The flagship will continue until at least 2027, says Ferrari, but with multiple changes to its structure, funding and leadership. Earlier this year Kinaret departed to make way for Patrik Johansson, formerly vice-director of the project.

Following the end of the main project, the flagship’s project to integrate 2D materials into silicon wafers that launched in October 2020 will still be funded through Horizon 2020 for another year. But the structure of the rest of the flagship will change. ‘Instead of having two projects there’s going to be a dozen research and innovation projects running and they are linked together in a weaker fashion,’ says Kinaret.

With collaboration one of the biggest benefits of the flagship, there are concerns that the change in structure will damage the formation of new networks. ‘The idea is that this will be the continuation of the flagship, but it’s not the same, these projects will be more independent,’ says Zurutuza. ‘Before, the flagship had a more coherent approach and was more focused. The collaborative work will continue but in a different, less coherent form. The challenge is to see how these small projects come together and join forces, although each of us will have our own objectives,’ she adds.

The years have also seen the fortunes of the flagship’s UK partners falter too. First Brexit and then the UK’s delayed association to Horizon Europe created significant challenges. The number of UK participants in the flagship under Horizon Europe is considerably lower than it was during Horizon 2020. Ferrari notes that although the UK was never ‘out of the flagship’ the past two years since Brexit have been ‘extremely hard’.

‘The main problem has been the fact that the UK was not able to be part of certain parts of the [Graphene Flagship] consortium related to European integration and the negative feeling towards the UK within the commission; many people in Europe were scared to put UK partners in the proposals,’ he explains.

‘It has been extremely hard to be part of budgets, it has been extremely hard to be part of the governance, my position has come under attack … but the good work we have done over the years has been recognised and luckily on the 7 September there was the announcement that the UK is back in Horizon Europe,’ he adds.

Although the flagship was originally slated to last 10 years, the work with graphene and other 2D materials is far from complete. Zurutuza says that she sees future applications for graphene in photonics, biosensors, optoelectronics and telecommunication. However, there are still hurdles to overcome. ‘One of the challenges that has not been solved yet is the integration of graphene – how to put it in the product, how to integrate it into existing manufacturing flows. When that is achieved, graphene will hit the market,’ she says.

But the future is not limited to graphene. Kinaret says that although graphene was the first two-dimensional material discovered, we now know that there are about 6000 out there and only 100 or so have been studied in any detail.

Now work is ongoing to set up new European partnerships such as Innovative Materials for EU which will bring together the Graphene Flagship with the Advanced Materials 2023 initiative.

‘If funded we will see an extremely large amount of money – even larger than the flagship – devoted to 2D materials like graphene but also all the other advanced materials together for the next 10 years,’ says Ferrari.

No comments yet