The UN’s plastics treaty negotiations have faced many hurdles, but delegates are getting closer to a final agreement

Next week, delegates from almost every UN member state will meet in South Korea for what is meant to be the fifth and final round of negotiations for a global treaty to end plastic pollution. But with major disagreements remaining between member states on the treaty’s scope, it is unclear as to how rigorous the final agreement will be, or if it will even be possible for an agreement to be reached without further meetings.

The meeting in Busan is the culmination of two years of talks, but it has been far from an easy journey. Concerns have been raised throughout the process, including about delaying tactics used by some countries seeking to weaken the treaty, the presence of large numbers of industry lobbyists at the meetings and the apparent side-lining of independent scientific expertise.

A slow start

In March 2022, UN member states agreed to negotiate a legally binding treaty to tackle plastic pollution. Two months later, prior to the first official round of negotiations, a meeting was held in Senegal to establish rules for the negotiating process. ‘Most of the rules were accepted, except for one,’ explains Bethanie Carney Almroth, an expert on the effects of plastic chemicals in the environment from the University of Gothenburg, who has followed the negotiations closely. ‘That [rule] was about voting rights and decision making in the negotiations and there was no decision on how decisions should be made when there’s no consensus.’

What became clear to me at the first meeting, and to many people, was that this is a health issue

Margaret Spring, International Science Council

‘In practice, they’ve been working under consensus rules because of that,’ she adds. ‘And that … has led to individual countries’ ability to block action, which they have utilised.’

When the first official round of negotiations kicked off at a meeting in Uruguay at the end of 2022, things got off to a slow start. According to Margaret Spring, an environmental policy expert who chairs the International Science Council’s expert group on plastic pollution, the meeting was ‘really more like a preparatory meeting than an actual negotiating meeting’.

She explains that, because the negotiations were convened by the UN Environment Assembly, ‘A lot of countries … really thought of this as a waste treaty and many of the negotiating delegates were from environment ministries,’ she notes. ‘But what became clear to me at the first meeting, and to many people, was that this is a health issue … [but] the health ministers hadn’t really been involved.’

‘There’s a lot of learning that’s been going on in this treaty process, and that is happening while negotiations are trying to proceed and so we’ve had a slower start than I think a lot of people would have expected or desired,’ adds Spring.

Science sidelined

Another contentious issue has been the lack of official channels through which independent experts can engage with negotiators to help inform the drafting of the treaty.

‘Science itself has been largely sidelined in this process, unfortunately,’ says Spring. ‘There is no provision for special engagement for the independent scientists or the International Science Council, which is a federation of the national and royal academies around the world.’

‘It’s also not really had a place for the UN agencies, whether the World Health Organization or other expert groups,’ she adds. ‘We all are observers and the negotiations are really by the delegations, so that has been frustrating.’

Carney Almroth explains that initially it was very difficult for academics to even attend the meetings as observers, as the United Nations Environment Programmes’ (UNEP) rules for accreditation dictate that institutions must be not-for-profit and non-governmental. ‘[This] effectively excluded the vast majority of universities,’ she notes.

While some academics have been able to attend the meetings if they can provide strong enough guarantees of their institutions’ academic freedom, many have been excluded. Others have had to find workarounds to attend – Carney Almroth attends as part of the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation’s delegation, rather than as a representative of her university.

In an effort to provide impartial scientific advice to government delegations, Carney Almroth has taken a leading role in the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty. The group has around 400 members from over 60 countries and bars industry-funded researchers from joining, to avoid potential conflicts of interest.

Despite this, representation of independent scientists at the negotiating meetings has been far outweighed by the presence of industry lobbyists. At the previous meeting in Ottawa, almost 200 industry representatives attended, more than three times the number of independent scientists.

Industry’s influence

Kara Law, an expert on ocean plastic pollution from the Sea Education Association, recalls seeing evidence of this lobbying effort outside the main conference centre. ‘When I was in Ottawa, there was one hotel I went to for a side event before the meeting and … the place was plastered with pro-plastics industry stuff like pictures of a child in a hospital bed saying “lives being saved by plastic”,’ she says. Law also recalls seeing similar adverts on billboards mounted on vans that were driving around the city, as well as on monitors in the airport when she was waiting to fly home.

‘The big industries are at the meetings, Dow and DuPont and BASF and Ineos and Sabic and the branch organisations, the [American Chemistry Council], the [International Council of Chemical Associations] and Cefic – they’re all there. They have a very different economic power than our group does … so it’s a very different power imbalance,’ says Carney Almroth. ‘They have very different access to get behind closed doors, to meet with delegates, to assert their influence over decision makers.’

Last month, more than 100 NGOs wrote an open letter to the UN secretary-general expressing concern that the UNEP’s executive director, Inger Andersen, had repeatedly used language echoing some of the plastic industry’s main talking points. They noted that her comments have since been used by industry representatives to argue against the inclusion of proposed treaty measures that would cap levels of plastic production.

Carney Almroth and many of her colleagues have also raised concerns that plastic industry lobbyists are now using tactics previously used by the tobacco industry to attack independent scientists who are raising the alarm about their products.

I have filed harassment reports with the UN about this kind of behaviour

Bethanie Carney Almroth, University of Gothenburg

‘When things aren’t going well for them, they start trying to undermine the credibility of scientific publications … and trying to create doubt around their validity, and when that doesn’t work, they start with character assassination of scientists and trying to undermine the credibility of individual scientists,’ she says. ‘And when that doesn’t work, they move into intimidation and harassment tactics around individual scientists, which is where they are now – they’re doing this to our scientists.’

‘They’re publishing articles about us in their branch newsletters and they are writing emails, they’re trying to get our work retracted, and they do yell at us and intimidate us in the meetings,’ she adds. ‘I have filed harassment reports with the UN about this kind of behaviour and spoken publicly about it because I can, because I’m a very safe person – my employment is safe, Sweden has anti-Slapp legislation … I know people that live in countries where public participation and environmental-rights and human rights defenders are not physically safe.’

Deadlines approaching

As the negotiations have progressed, a divide has grown between countries that want the treaty to be as rigorous as possible and those – mainly countries with large petrochemicals industries – that have sought to delay and defang the treaty. Sixty-five countries have signed up as part of a ‘high-ambition coalition’ determined to end plastic pollution by 2040. Meanwhile, countries including Russia, Iran and Saudi Arabia have been accused of trying to derail the talks.

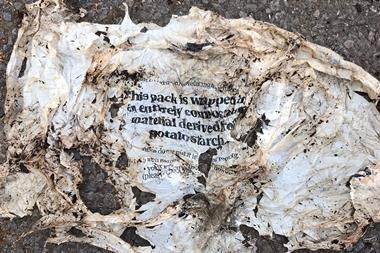

Tactics have included blocking work from being carried out between the negotiations to slow the treaty-writing process and attempting to shift the focus of the treaty away from the need to cut plastic production and towards waste management and recycling.

When an initial draft treaty was presented by the negotiation’s first chair, the more resistant countries responded by inserting their own text. As a result, the draft text ballooned from around 30 pages in length to almost 80, including more than 3000 sections that would still need to be negotiated.

I think it would be unrealistic to have everything decided perfectly in a treaty that’s concluded this year

Margaret Spring, International Science Council

Realising that it would be virtually impossible to negotiate all of those clauses in the remaining timeframe, the current chair Luis Vayas Valdivieso reached out to all of the delegation heads and created a new unofficial document called a ‘non-paper’.

‘[The non-paper] was a reflection of what he was hearing and where there was convergence,’ says Spring. ‘And so [three] weeks ago, he came out with this third non-paper, which showed where he felt that we could start negotiations in a more clean way in Busan, showing areas of convergence, which was great, and then showing some areas where we need to work.’

Some of the crucial points that remain unresolved relate to whether the treaty will enforce limits on plastic production and whether any specific chemicals or classes of chemicals will be banned from use in plastic manufacture.

Capping production of virgin plastics, in particular, has been a major bone of contention. While some states have firmly opposed this, others see it as integral to an effective treaty. After the fourth round of negotiations, many of the national negotiating delegations signed a declaration known as the ‘Bridge to Busan’ emphasising that ‘addressing the unsustainable production of primary plastic polymers is not only essential to ending plastic pollution worldwide; it also represents one of the most efficient and cost-effective approaches to managing the plastic pollution problem’.

In August, the White House announced that the US, while not a member of the high-ambition coalition, would also support production limits. That move provoked outrage among industry representatives, with the president of the Plastic Industry Association stating that the decision favoured ‘misinformation spread by anti-plastic activists’.

‘Things are shifting,’ notes Carney Almroth. ‘Not everyone’s on board, obviously, but the playing field has shifted towards more upstream measures and towards more support for those kinds of really ambitious and effective obligations in the treaty.’

However, Spring notes that any agreement to reduce plastic production is likely to be inferred in the text rather than linked to a specific target. ‘I have not seen any proposals yet from any countries with a numeric target … or a cap to levels of a previous year,’ she says. ‘However, what I have seen is language like “agreeing to sustainable levels of production”. Now, if you look at the modelling, what we know is that we are not at a sustainable level of production now – so if we agree to a sustainable level of production, one would assume that that would imply a reduction.’

The question of whether certain classes of chemicals could be banned in plastic production is another that has received growing attention in recent months. Earlier this year, the PlastChem project identified more than 16,000 chemicals associated with plastic production. Many scientists point out that limiting the types of chemicals that can be used to make plastics would help to reduce the health risks that they pose and also make it easier to recycle the material.

Spring notes that a bare minimum would be to improve the monitoring and reporting around plastic production and releases to the environment. ‘The problem is that there’s no reporting. There’s no transparency of what’s in plastic,’ she says. ‘There’s no actual annual reporting of how much plastic is being produced, except by industry associations – and that those data are not complete, or they cost too much to obtain.’

When approached by Chemistry World, the World Plastics Council – a global trade group representing the plastics industry – was unable to provide details on its positions regarding production caps, bans on particular classes of chemicals, or increased monitoring and reporting of chemicals used in plastics manufacture. However, the group released a statement on Tuesday that describes caps and bans as ‘blunt and counterproductive measures’. It also provided a list of recommendations for the treaty that predominantly focus on ways to increase the amount of plastic that is recycled globally.

Just the start

As the deadline for the negotiations approaches, it seems unlikely that the final text will keep everyone happy. However, Spring is hopeful that it can serve as a ‘start and strengthen treaty’, laying the foundations for improved efforts to tackle this huge and complex issue. ‘I think it would be unrealistic to have everything decided perfectly in a treaty that’s concluded this year,’ she says. ‘But what we’d like to see is obligations to address plastic at every stage of the life cycle, including monitoring, and a science process to provide advice as needed by the policymakers – as we do in other treaties, whether it’s the ozone treaty – the Montreal Protocol – or [the Minamata Convention on mercury].’

That view is shared by Law, who says that the fact that the treaty negotiations are happening at all brings grounds for optimism. ‘I’ve been working on ocean plastics for almost 20 years – when the world was really not aware of this problem,’ she says. ‘And sometimes when I stop and think about it, it still brings awe that we have an international negotiating process even happening.’

‘Is it going to address every step along the life cycle in the way that many or the majority of people want to see? Probably not,’ she adds. ‘But it’s probably most important that we get something done to say this is something we’re going to continue to iterate on and find the places of agreement and work on this, and keep it at the top of the global agenda.’

No comments yet