Biomolecular condensates are fluid blobs that form inside cells and perform all kinds of vital functions. Now researchers have identified a new way for them to exert their influence: through changes in the electrochemical gradients at their interfaces.

Yifan Dai of Washington University in St Louis and his co-workers have found that condensates don’t stay the same while they persist, but ‘age’ in a way that alters their electrochemical properties.1 The researchers believe this might supply a means for cells to control condensate properties and functions, and that the findings could have implications for therapeutic interventions in condensate-related diseases.

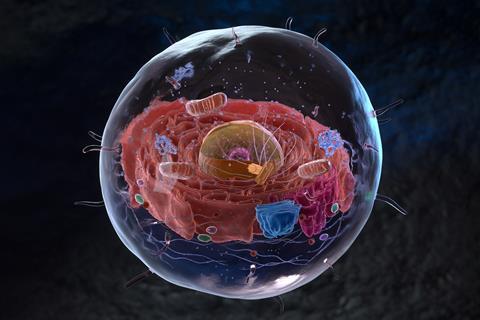

Biomolecular condensates are loose aggregates, typically tens of nanometres to a few micrometres in size and made from proteins and sometimes RNA. They form inside cells as membrane-less compartments that can segregate their constituents from the surrounding cell fluid. First recognised as such in 2009, condensates have in fact been seen by cell biologists for almost 200 years as microscopic blobs that were given vague names such as speckles, granules and bodies. They are considered to arise through phase separation and their material properties can range from liquid-like to gels or even quasi-solids.

Most condensates are ephemeral, forming in response to some signal, such as cell stress, and eventually dissipating. Among the functions they perform are as storage compartments for biomolecules, facilitators of DNA repair and hubs of gene regulation. Disruption of normal condensate formation seems to be associated with disease – for example, they have been implicated in neurodegenerative conditions caused by faulty protein aggregation.

Recently, Dai and others have found evidence that, as well as acting to sequester proteins and other molecules, condensates might play roles in cell biology because of the interfaces they create, where gradients in concentration can develop. Such non-equilibrium distributions of ions, for example, can generate electric fields or redox gradients that appear to have catalytic activity.2,3

Growing old

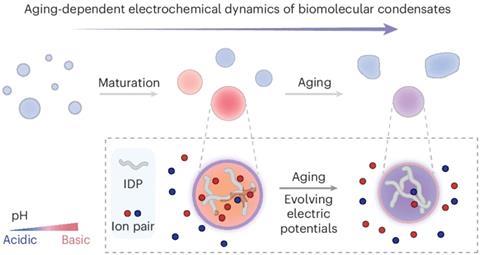

Now the researchers have studied how the electrochemical properties of condensates change over time as a result of changes in the interactions between the proteins and their solvent. The team studied a model condensate in vitro, made from a polypeptide that mimics a typical condensate-forming protein. Using a pH-dependent fluorescent dye, they saw that the condensates changed from neutral pH to basic during the first two hours after their formation, but then gradually switched from basic to acidic over the course of a day or so. Older condensates acquired internal structure: a more acidic core surrounded by a higher-pH shell. Using a molecular-motion-dependent fluorescence method, Dai and colleagues could see that these changes were accompanied by changes in the viscosity of the condensate medium, presumably reflecting changes in the bonding between the molecular components.

The researchers also measured the potential difference between the dense condensate phase and the surrounding dilute phase by centrifuging them to gather the dense phase together and then using electrochemical potentiometry – inserting electrodes into the fluids – to measure the electric field at different stages of condensate ageing. This potential decreased over time, consistent with the reduced pH gradient in older condensates. These electrochemical changes were accompanied by a decreased ability of the condensates to facilitate a redox reaction. And while the condensates promoted the formation of fibrillar aggregates of amyloid-b – structures linked to Alzheimer’s disease – for younger condensates the fibrils remained confined to the surface but in older condensates they could grow into extended, tangled networks.

The researchers say the work shows that condensates with seemingly identical compositions might not have the same properties or functions if they are different ages. Might these changes just be a passive effect of ageing? Dai argues that, on the contrary, they are likely to be actively controlled by processes involving the condensates themselves, for example, because of how the interactions of their component proteins are dependent on pH or on redox-sensitive crosslinking. ‘The redox activity of condensates can set up a self-feedback loop to alter protein properties,’ he says.

Dai also argues that changes in protein interactions will induce changes in the state of their hydration in water, which can alter the distribution of ions inside the condensate. ‘Biologists focus a lot on biomolecules, but the solvent context that these biomolecules are functioning in is actually equally important,’ he says.

‘What is fascinating is that these results show that the local chemical environment of condensates can change as a function of time,’ says biophysical chemist Tuomas Knowles of the University of Cambridge. ‘This finding may have implications for understanding the aberrant biology associated with condensates ageing into protein aggregates in protein misfolding diseases.’

It remains to be seen how general the findings are, since condensates are formed from various biological macromolecules and have diverse structures and properties. ‘Future studies are necessary to establish whether or not such a mechanism represents a generic phenomenon for a wide range of intracellular condensates derived from a multitude of proteins and nucleic acids,’ says biophysicist Samrat Mukhopadhyay of the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Mohali.

References

1 W Yu et al, Nat. Chem.,2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41557-025-01762-7

2 X Guo et al, bioRxiv, 2024, DOI: 10.1101/2024.07.06.602359

3 Y Dai et al, Chem, 2023, 9, 1594 (DOI: 10.1016/j.chempr.2023.04.001)

No comments yet