Analysis of glass and ceramic shards retrieved from an archaeological excavation in Sweden could reveal new insights into alchemical experiments carried out by the Renaissance astronomer, Tycho Brahe. The researchers found traces of nine chemical elements on the inner and outer surfaces of the fragments including copper, gold, zinc and tungsten.

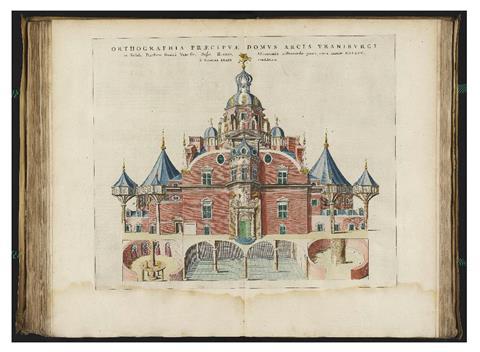

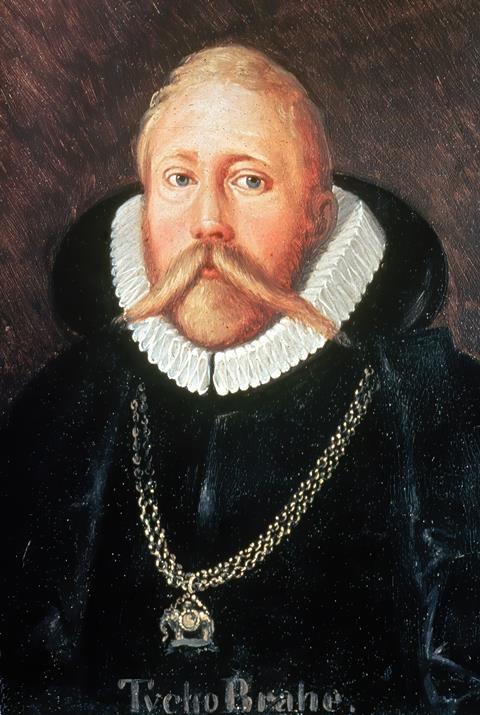

Brahe, who lived between 1546 and 1601, is well-known as an astronomer, but he also had a less well-documented interest in alchemy. In 1576, King Frederik II of Denmark offered Brahe the island of Ven as a lifelong fief, saying he wanted to support Brahe’s work. Brahe accepted and between 1576 and 1580 he erected Uraniborg, a unique combination of palace, observatory and alchemical laboratory

‘It was like the Cern of the day,’ says Kaare Lund Rasmussen, professor emeritus in the department of physics, chemistry and pharmacy at the University of South Denmark, and one of the researchers leading the study.

While Brahe published books and articles on his astronomical work, very little is known about his alchemical studies at Uraniborg. ‘The story about Tycho is always written about the astronomy,’ Rasmussen says. ‘And the reason is that he wrote very little about his alchemy – he wanted to keep [it] secret – whereas the astronomy he published books … and that came out to the world, whereas the medicine making did not.’

After his death, Brahe’s palace and observatory on Ven was demolished and the stones reused for new, humbler buildings. However, in 1824, the remains of the observatory were unearthed, along with traces of two ovens from his laboratory. A further archaeological dig in 1988–1990, which concentrated on the garden and surrounding buildings, unearthed fragments of glass and ceramics that may have come from the laboratory.

Rasmussen and Poul Grinder-Hansen, a historian at the National Museum of Denmark, were then tasked with convincing the museum in Lund, Sweden, who had possession of hundreds of shards taken from the site, to allow them to carry out analysis on them. ‘They weren’t all too eager to do that,’ says Rasmussen. ‘[But] they gave me five shards.’

Cross sections of the shards were analysed for 31 trace elements with the aim of detecting any traces of the chemical substances on the inside or outside of the shards. ‘[We were] very lucky in the sense that [for] one shard there was nothing on either side of it,’ says Rasmussen. ‘The others, there were different elements that were clearly increased or enriched and so for the first time, we have this light cast into this laboratory.’

The researchers found traces of nine chemical elements on the inner and outer surfaces of the fragments – copper, antimony, gold, mercury, nickel, zinc, tin, tungsten and lead.

The presence of copper, antimony, gold and mercury was consistent with previous research suggesting they may have been used in three of Brahe’s medical preparations. One for the prevention and treatment of an epidemic disease or other infectious contagion, a second for the treatment of epileptic diseases and a third for diseases affecting the skin and blood, such as scabies, chronic venereal diseases and elephantiasis.

‘Copper, antimony, gold and mercury were known to be used in the recipes,’ says Rasmussen. ‘But the other ones, nickel, zinc, tin, tungsten and lead, they were not mentioned anywhere. So, something else must have happened in the alchemy lab … but tungsten, that is really, really hard, because that was hardly invented [at that time].’

The researchers speculate that a tungsten-containing mineral may have been used in the laboratory because of mistaken identification or its chemical composition being unknown.

Umberto Veronesi, an archaeologist and heritage scientist based in Lisbon, Portugal, says what he found ‘particularly interesting and exciting’ about the study was that it was talking about a ‘very high profile person’ – which he says is ‘a rare occurrence’ in archaeology. ‘The beauty of archaeology is that it very often speaks to us about anonymous people – especially when it comes to this kind of scientific laboratories … we don’t really know the names and the interests of the people who are working there, they are usually quite anonymous,’ he adds. ‘That’s the big contribution of this paper, because it is like an open window, a very rare opportunity to look into what a very important person in the history of science was doing.’

Veronesi says that, having worked with similar materials before, he wasn’t surprised by the identified elements as they were consistent with someone interested in alchemy.

‘What’s important is that they found certain elements on the surfaces, especially the inner surfaces of these vessels, and that these are related to operations that could be metallurgical operations, but they equally could be medical operations,’ he says.

He adds that it would have been useful for the researchers to discuss in more detail the findings of their analysis that did not have a clear explanation.

‘They mentioned that there are some elements, like copper, like zinc, which cannot be matched to Brahe’s recipes and that’s exactly where I would have tried to dig a little more – it could tell us something, for example that Tycho Brahe was also working with copper alloys for whatever purpose, or sometimes they were trying to make alloys in order to understand how single elements and single metals work when, when treated in specific ways.’

References

K L Rasmussen and P Grinder-Hansen. Herit. Sci., 2024, DOI: 10.1186/s40494-024-01301-6

No comments yet