There are always uncertainties when animal studies are extrapolated into human effects

There are always uncertainties when animal studies are extrapolated into human effects. But when it comes to a plastic that children put in their mouths, toxicology studies that say a commonly-used chemical is harmful can be compelling for consumers. Such is the case with Bisphenol A (BPA) - identified as a hormone mimic in experiments in rodents more than 70 years ago, and, as toxicological evidence emerged, gradually brought under the control of industry regulators. Now the debate over its use has erupted once again.

And the language is emotive. In February, a consortium of US and Canadian environmental groups - the Work Group for Safe Market - released a report entitled Baby’s Toxic Bottle stating that 19 polycarbonate bottles they had tested leached BPA when heated. The group called for an immediate moratorium on the use of BPA in all baby bottles, as well as in food and beverage containers. The data on BPA is now under full review by the Canadian Public Health Authority, Health Canada.

Bisphenol A (2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) propane) is one of the highest volume chemicals produced world-wide. It is a monomer used to make polycarbonate and epoxy resins. Roughly three million tonnes per year go into a huge range of products including reusable plastic bottles and table-wear, CDs, electrical and sports equipment, dental restorative materials, paints and adhesives, and the protective liners in metal food and beverage cans.

It has been known as an ’oestrogenic chemical’ since 1938, when Dodds and Lawson dissolved 100mg in sesame oil and injected it into spayed rodents. In the 70 years since, the molecule has been shown to disrupt chemical signalling in the complex network of glands, hormones, and cell receptors that make up the endocrine system. Links have been proposed between BPA exposure and cancer, obesity, diabetes, hyperactivity, early onset of puberty, low sperm counts, and damage to the ecosystem such as feminisation of fish, reptiles, and birds.

A safe dose?

But, as Paracelsus noted in the 16th century: ’It is the dose only that makes a thing not a poison.’ BPA polycarbonate and epoxy resins are widely used because the levels of free BPA (from unreacted monomer and the result of polymer hydrolysis) are assumed to provide a dose that is low enough to be safe.

’Residual BPA concentrations in polycarbonate plastics are generally less than 50 ppm,’ says Steve Hentges, executive director of the American Chemistry Council’s Polycarbonate/BPA Global Group. ’The industry acts responsibly - we have to know that our products are safe.’

David Smith, technical manager with the Metal Packaging Manufacturers Association in the UK agrees: ’[These coatings] have been used for many decades. The minute parts per billion level of residual BPA in the resin represent no threat to consumer health,’ he says.

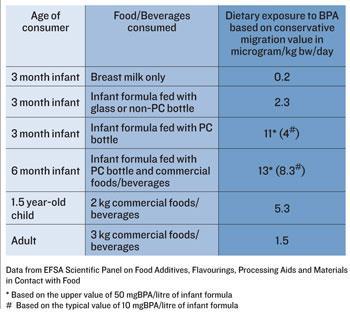

And European and US authorities seem satisfied with this assessment. In September 2007 the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) increased its Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI) for BPA to 50 m g/kg body weight/day. This is, the EFSA’s scientific panel concluded, the amount that someone could safely ingest every day - well above its own estimates of adult dietary exposure (1.5 m g/kg body weight/day). The reference dose (maximum acceptable oral dose of a toxic substance) established by the US Environmental Protection Agency is also 50 m g/kg body weight/day.

But public fears about BPA have not been allayed by such reassurances. In October 2007 the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published results of its analyses of urine samples obtained from 2517 people aged 6 years and older. BPA was detected in 93 per cent of those tested, and widespread exposure to BPA set off alarm bells - though numbers corresponded to average exposures well below the TDI.

In particular, the significantly higher levels of exposure for infants fed on milk or formula from polycarbonate bottles has worried parents groups and activists, and has been used extensively in advertising for baby bottles made from glass or polyethylene. Some researchers have reported that the human foetus is likely to be exposed to BPA throughout foetal development, at levels higher than those measured in adult blood. This has caused specific concern because endocrine disruption may be particularly harmful during the early stages of life.

Animal trials, human debate

In August 2007, a review written by researchers who had been studying BPA was published in the journal Reproductive Toxicology. It weighed up the entire body of peer-reviewed work (more than 700 papers) presented at an open forum held in the US entitled ’Bisphenol A: An Expert Panel Examination of the Relevance of Ecological, In Vitro and Laboratory Animal Studies for Assessing Risks to Human Health’. The review concluded that ’the wide range of adverse effects of low doses of BPA in laboratory animals exposed both during development and in adulthood is a great cause for concern with regard to the potential for similar adverse effects in humans’.

Ana Soto, professor of anatomy and cellular biology at the Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, US, a contributor to the report, is convinced that BPA is a problem. She has studied the potential link between BPA and cancer. ’[We have shown] that foetal exposure at environmentally relevant levels, down to 25 ng/kg-body-weight, increases the propensity to mammary cancer in rats, and alters the development of the mammary glands,’ she says. ’We don’t yet have a complete picture, but the weight of evidence suggests that BPA is harmful.’

The ACC’s response to the report was open dismay. Hentges described it as ’far less sound’ than the ongoing evaluation by the National Toxicology Program’s Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction (CERHR) - which the ACC supports. But the CERHR’s own report, from its panel of independent government and non-government scientists (researchers who were not working on BPA-related research), did not lay the issue to rest. The panel focused on animal studies in which BPA was administered orally, ignoring those where BPA was injected, and expressed negligible concern about the effects of current exposure to BPA in the general adult population. But it did express concern about the effects on pregnant women and foetuses, and on infants and children. The NTP’s final report, which will be presented to regulatory agencies, is due in summer 2008.

The debate has been heated, with accusations of bias and conflict of interest flying, but all groups agree that further research is required. In particular there is a need for work on the molecular mechanism to establish, or disprove, the link between BPA and biological effects. Studying the direct effects of the chemical on humans remains an impossible task.

Yasuyuki Shimohigashi, at Kyushu University in Japan, leads one of the groups working on this issue. Earlier studies showed that the binding of BPA to the estrogen receptor ER a is several orders of magnitude weaker than the binding of the natural hormones. This added to the sense of security - BPA was defined as a very weak environmental estrogen.

In a January 2008 Environmental Health Perspectives paper, Shimohigashi’s team presented an alternative idea: that BPA has a high affinity for a specific receptor called estrogen-related receptor- g (ERR- g ). ’Our work raises the possibility that BPA-related endocrine disruption might be mediated through ERR- g . This is important because of the strong expression of the receptor in the placenta and also in the foetal brain - BPA binding could affect the receptor’s role by activating transcription at the wrong times,’ he explains.

Over the past few years the media, particularly in the US, has enthusiastically pursued the BPA story, with both Fox News and CBS issuing lists of ’toxic baby bottles’. In June 2006 the city of San Francisco acted to ban BPA in products designed for children under 3 - quite a challenge given the wide range of materials that contain it (the law was never implemented and was repealed in 2007).

In January 2008, US Congressmen John Dingell and Bart Stupak initiated an inquiry with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the manufacturers of infant products regarding BPA. ’Our primary goal is to protect infants from a potentially harmful chemical,’ says Stupak. ’Our investigation intends to examine how the FDA determined this chemical to be safe for use in infant formula cans.’

The devil you know?

But if there is a will for change, replacing the material may not be easy. Polycarbonate has particularly good materials properties - impact strength and transparency - for applications such as eye-glasses and baby-bottles. BPA-based epoxy resins are very good materials for lining cans. ’They have extremely good adhesion to metal substrate, very good resistance to metal forming operations, and to high temperature in-can processing, and low taint,’ says Smith.

’One should also reflect on the risks of alternatives,’ warns David Ball from the Centre for Decision Analysis & Risk Management, Middlesex University, UK. ’Would they be any safer?’

’None of the alternatives have been studied even remotely as well as bisphenol A,’ says Hentges ’Restricting it would not be erring on the side of safety but erring on the side of the unknown.’

Fiona Case is a freelance science writer based in Vermont, US

No comments yet