Figures show that funding for science has actually fallen as the nation’s economy has grown rapidly

As India’s prime minister Narendra Modi prepares to face an election within a year, spending on science does not appear to be a top priority. The budget presented last week – the government’s last substantive one of this parliament – remains a mixed bag offering civilian science near stagnant funding when measured as a share of GDP.

The latest budget pegs civilian R&D 11% higher than last year. Defence research, however, secured a whopping 29% increase. Other sectors that received a boost include space with an 18% increase, earth sciences with a 13% increase, agricultural research a 12% increase, while new and renewable energy got a 26% boost. Total government spending on R&D outlined in the budget amounted to INR536 billion (£6 billion).

The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) – which runs 38 leading research laboratories – received a 3% raise. Since last year, it has been facing a serious funding shortfall, following a government diktat that it should fend for itself.

‘During last year, we have been able to raise 25% of our budget from non-CSIR sources and by March end, this figure will touch 30%,’ Girish Sahni, director general of CSIR tells Chemistry World. ‘This is very encouraging but we don’t want to overdo it.’ Sahni rebuffs criticism that research has been harmed by the need to raise funds and says the organisation is being transformed.

The latest data released by the science ministry reveals that while India’s gross expenditure on R&D – public and private spending combined – went up nearly five-fold since 2004–05, as a percentage of GDP it has been plummeting since 2008–09, hovering at 0.69% of GDP in 2015 – the lowest among the BRICS nations. In contrast, South Korea spent 4.23% of GDP on R&D, China 2.07% and the US 2.74%.

Top scientists have voiced their frustration at current funding levels. ‘We just cannot compete as a nation and only a few individuals may succeed,’ says chemist CNR Rao, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru Center for Advanced Scientific Research and a science adviser to former prime minister Manmohan Singh. ‘I find that in a meeting dealing with cutting edge [science and technology] frontiers, there will be very few Indian scientists, compared to a few hundred from China and Japan,’ he adds.

India’s science policymakers have advocated that India devote 2% or more of its GDP to science for nearly three decades. Rao says that if India is to make major contributions in certain key areas, such as energy, it will have to invest judiciously in people and institutions.

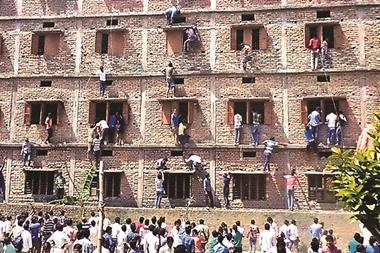

‘We better hurry and do something since we may even lose what we have,’ cautions Rao. ‘If we want India to grow on the strong foundations of [science and technology], we are not doing enough for this sector or for the education sector.’

No comments yet