Grid system sorts out graphene family tree

A grid-based system to sort and classify graphene and similar materials has been developed by a team of European researchers. Thanks to graphene’s extreme chemical and mechanical stability, high electronic conductivity and biocompatibility, new graphene-based materials (GBMs) are cropping up in fields as diverse as photonics, energy generation and biomedicine. But such rapid growth of the graphene ‘family’ raises an important question: how should new GBMs be identified?

One answer, developed under the European Union’s Graphene Flagship, is a classification system based on integrating GBMs’ physical and chemical properties into a single framework. Categorising graphene types like this makes it easier to explore their potential applications.

‘Every time there is a new field of research there is a rush for naming materials, processes and phenomena,’ explains Peter Wick, a member of the Health and Environment team – one of several groups operating under the Graphene Flagship – that put the framework together. ‘This causes confusion, with multiple teams working on the same thing and calling it differently.’ As one of the EU’s biggest ever research initiatives, the Flagship is a pan-European research collaboration aiming to drive cutting edge graphene research into commercial technology within the next decade. ‘Since the Graphene Flagship is a combined research effort it is essential to have a common vocabulary,’ Wick adds.

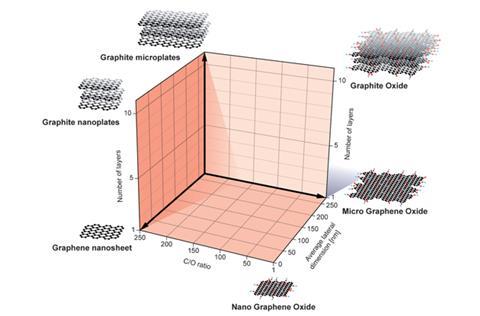

The new system classifies GBMs according to where they lay on a 3D grid defined by three parameters; the number of graphene layers, the average lateral size, and the carbon-to-oxygen atomic ratio. For example, graphene nanosheets occupying one corner of the grid evolve into graphite microplates as the number of layers reaches ten and their size increases to 250nm. This, the team believes, is an initial step towards categorising distinct graphene types using three easy-to-measure and quantifiable characteristics.

Wick, who is based at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, also hopes that the framework spells a means of relating the physical chemical properties of different types of GBMs with their biological effects. ‘By that we can support the safe and sustainable use of graphene-based applications, in particular in biomedical applications,’ he says.

Developing a universal classification system for graphene is of crucial importance, says Weibo Cai, who researches the biomedical applications of graphene- and silica-based nanomaterials at the University of Wisconsin, US. He says the framework Wick and colleagues have developed is based on useful properties and could have a ‘profound and multi-faceted impact in biomedicine’.

References

P Wick et al, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2014, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201403335

No comments yet