Two new techniques use DNA to build crystals of nanoparticles more easily

Two papers in Nature have each shown a simple way to build designer crystals from nanoparticles, using DNA as ’glue’. Both methods show promise as a cheap way of mass-producing complex materials like photonic crystals.

In one of the articles[1], Oleg Gang and co-workers from Brookhaven National Laboratory, New York, US, showed that DNA bound to nanoparticles influences the interactions of one nanoparticle on another - thereby determining the bonding structure of the nanoparticle crystal.

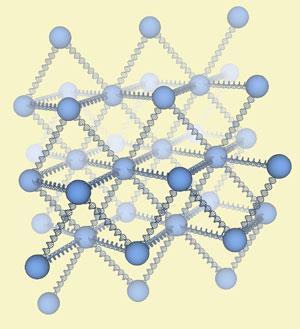

The team attached strands of DNA to one batch of gold nanoparticles and complementary strands of DNA to another. When the nanoparticles were heated and cooled, the complementary strands of DNA stuck to each other, forming an ordered lattice of nanoparticles. The team were also able to change the spacing between nanoparticles in the crystal lattice by altering the length of their DNA strands. However, if they made the DNA strands too short or rigid, they found the nanoparticles clumped together and didn’t ’set’ into ordered crystals.

’The ability to engineer such 3D structures is essential to producing functional materials that take advantage of unique properties at the nanoscale,’ Gang told Chemistry World. ’Using a broad range of newly synthesised nanoparticles we are developing a concept of "artificial atoms", from which a broad range of new materials can be built.’

Perhaps even greater control is demonstrated in the second Nature paper[2] by Chad Mirkin and colleagues, from Northwestern University, US. Gold nanoparticles were similarly functionalised with DNA - but Mirkin and his team manipulated the reaction of the DNA strands themselves to make ordered crystals. By changing the sequence of the DNA ’linkers’ between the nanoparticles the team made two different crystal forms - face centred cubic and body centred cubic.

Mirkin told Chemistry World that he sees the DNA links between the nanoparticles like bonds between atoms. ’I came up with [the idea] back in 1995 when many in the research community began making the comparison between a nanoparticle and an atom. The next logistical step is to build "molecules" where the "atoms" are connected to one another through some sort of bonding interactions,’ he said.

Both papers suggest the breakthroughs could be important for making ordered crystals on a large scale, for use in applications like photonic crystals, catalysts and separation membranes, and Mirkin’s company Nanosphere is already producing FDA-approved medical diagnostic tools based on this work.

Earlier attempts to make arrays of nanoparticles used solvent evaporation, where crystalline nanoparticles are left behind as a solvent evaporates. But unlike the new DNA-based methods, this method allows little control over the kind of nanoparticle structure obtained.

John Crocker, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, US, has studied the use of DNA in assembling nanoparticle crystals. ’Gang and Mirkin have developed a much more versatile method for making nanoparticle arrays,’ he told Chemistry World. ’If a future metamaterial engineer requires a specific nanoparticle composition, size, array structure and spacing, this DNA method is more likely to be able to build it, compared with the earlier solvent evaporation method.’

Jonathan Edwards

References

1 Nykypanchuk et al, Nature, 2008, 451, 549 (DOI: 10.1038/nature06560)

2 Park et al, Nature, 2008, 451, 553 (DOI: 10.1038/nature06508)

No comments yet