As legal challenges fall flat, will industry’s claims of stifled innovation be borne out?

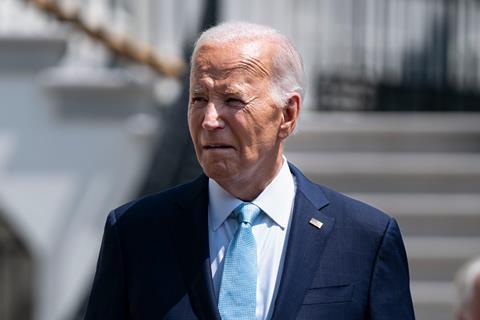

In 2022, US president Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) introduced a mechanism for the state-backed health insurance programme Medicare to negotiate drug prices directly with pharmaceutical firms. The industry’s response was scathing, with lawsuits claiming the move was unconstitutional, and dire warnings of stifling innovation and R&D investment.

With negotiations on the first batch of 10 medicines now complete, the response from some in industry appears to be one of reluctant acceptance. The government says the negotiated prices would have reduced its 2023 spending on these drugs by $6 billion (£4.6 billion) had they been in place for the year. However, because of the complexities of US healthcare payments and discounts and rebates negotiated between manufacturers and healthcare providers, the precise effects on manufacturers’ revenues and patients’ personal drug costs are less clear.

The IRA had instructed Medicare to negotiate with drug makers for high-cost, single-source drugs that had no generic or biosimilar competitors. The process kicked off in 2023, with new prices to go into effect in January 2026. The 10 initially selected drugs include treatments for diabetes, cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases, and cancer.

Legal challenges

The pharmaceutical industry has been critical of the new process, claiming it is unfair and will discourage R&D investment. Drugmakers launched multiple legal challenges against the negotiations, arguing that the IRA violates their constitutional rights.

‘It doesn’t give manufacturers any meaningful opportunity to get out of the negotiation programme,’ says Margaux Hall at US law firm Ropes & Gray. ‘Walking away would be a business decision to no longer commercialise drug products in the US.’

Companies are already changing their research programmes as a result of the law. This will result in fewer treatments for cancer, mental health, rare disease and other conditions

Trade group PhRMA

Bristol Myers Squibb’s suit, (BMS) launched in June 2023, asserted that the IRA amounts to taking property for public use without reasonable pay and violates the right of free speech, forcing companies to state that the price is the result of a true negotiation.

Merck & Co also sued, criticising ‘unconstitutional provisions’ of the law. AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk and Johnson & Johnson (J&J) similarly launched individual suits in courts across the country. These challenges, along with those of the US Chamber of Commerce and the industry group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) have so far been rejected or thrown out by judges.

The rulings have mostly been on procedural grounds, says Hall. ‘We haven’t had rulings in most instances on the substantive merits of the claims that were brought.’ In September, an appeals court ruled that PhRMA’s suit should not have been dismissed. While not ruling on the case’s merits, the judge appeared to be ‘somewhat sympathetic to the claims that industry is raising,’ according to Hall.

Inhibiting innovation

PhRMA has said that the IRA harms the incentives for medicine development: ‘Companies are already changing their research programmes as a result of the law, and experts predict this will result in fewer treatments for cancer, mental health, rare disease and other conditions,’ the group stated. BMS suggested last September that the IRA encouraged it to stop research into a first-line treatment for multiple myeloma, for example.

‘Our litigation against the Inflation Reduction Act’s innovation-damaging pricing provisions is focused on protecting our ability to continue developing transformative therapies and treatments for patients now and in the future,’ a spokesperson for J&J commented.

This signals to companies that the US government will reward truly innovative medicines, but pay less for products that are not much better than alternatives

Olivier Wouters, London School of Economics, UK

Small molecule drugs become eligible for negotiations 7 years after their first approval, while biological agents get 11 years’ grace. This could change firms’ regulatory strategies, points out Hall. ‘In areas like oncology, historically many manufacturers would launch a small-scale indication, while they continue to research large-scale indications,’ she says.

The law could disincentivise the launch of a small-market application, since it may make more commercial sense to only start the price-negotiation clock once firms have approval to treat access to more common – and hence more profitable – conditions.

There are other, similar effects: Alynlam, for example, has said it stopped a trial on RNA interference drug Amvuttra (vutrisiran) for a rare eye disease, as the drug already has an orphan drug indication for a heart condition. A single orphan drug designation exempts it from negotiations, but two designations would make it eligible. There are also suggestions that the rules could skew R&D further towards biological drugs, with their longer protection from negotiation.

Crying wolf?

‘This is quite a significant change in the US landscape, because historically companies have charged whatever the market will bear,’ says Olivier Wouters, professor of health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science, UK.

‘This signals to companies that the US government will reward truly innovative medicines, but pay less for products that are not much better than alternatives,’ he adds. It is standard practice in European countries to weigh a drug’s value and for government agencies to negotiate or decide on a fair price.

Wouters says that cramping innovation ‘is the usual bogeyman that industry invokes anytime there are measures aimed at putting downward pressure on prices.’ He adds that ‘industry uses this argument so often that it feels a bit like they are crying wolf.’

We haven’t seen as much pushback as we might, which may be a sign that there were some good faith negotiations

Jack Hoadley, Georgetown University, US

Companies have told shareholders, ‘effectively that the prices are not as bad as they expected or feared, though this wouldn’t be quite their wording,’ according to Jack Hoadley, emeritus research professor in health policy at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. ‘We haven’t seen as much pushback as we might, which may be a sign that there were some good faith negotiations and companies were willing to work with the government.’

Hall, who advises industry on pricing and the consequences of the IRA on drug R&D, disagrees. ‘The concern is still very high that this is an unlawful intrusion into the long-standing free market premise of the US,’ she says, ‘and that our robust pipeline of innovation is going to be eroded.’

Looking ahead

The government’s research prior to negotiations emphasised that the cost of the 10 selected drugs had ‘more than doubled from 2018 to 2022, going from about $20 billion to about $46 billion’, a rate of increase three times faster than other similar drugs under Medicare.

Other considerations include the drugs’ production costs; previous federal financial support; patents involving government-funded research; and revenue and sales of the drug in the US market. Seven of the ten drugs relied on at least one form of federal contribution or support relevant to their development, according to the December report.

We don’t know the pace at which the maximum fair price that applies to Medicare will spill over into the commercial market

Margaux Hall, Ropes & Gray

But judging the success of negotiations is not entirely straightforward, owing to the complex and opaque nature of the US healthcare payments system, which involves a convoluted network of discounts and rebates between manufacturers, healthcare providers and patients.

‘If negotiated prices are only slightly lower than current net prices, negotiation may not be a success, because the slight reduction would be offset by the fact that the manufacturers do not need to pay for [mandatory discounts],’ notes Inma Hernandez, pharma policy expert at the University of California in San Diego, US.

Some of the discounts may appear very significant when framed in terms of ‘list prices’ – but this is largely a distraction, explains Hernandez. ‘Comparison with list prices is misleading because drugs had high discounts before,’ she adds. The list price of Merck & Co’s diabetes drug Januvia (sitagliptin) is over $500, but discounts mean that the true net price was $195 (versus the new price of $113), as previously reported by Hernandez and her colleagues.

Nonetheless, Hall counters that the price setting is going to have wider market repercussions. ‘We don’t know the pace at which the maximum fair price that applies to Medicare will spill over into the commercial market,’ she says. ‘In the US, the commercial market remains the dominant market for health coverage.’

The government is expected to provide a rationale for its pricing decisions by early spring 2025. ‘There will be a lot of tea leaf reading by other companies,’ says Hall. Up to 15 more drugs will be selected for negotiations to become effective in 2027, with expectations including Novo Nordisk’s blockbuster diabetes and weight loss therapy Ozempic (semagulide). Another 15 will follow for 2028, and up to 20 additional drugs each year after that.

The IRA, however, remains unpopular with Republicans. ‘If [Donald] Trump is elected president and comes in with a Republican Congress, they might well repeal,’ says Hoadley. ‘It remains to be seen how this would play out. We’ve heard Trump at times say that the government should negotiate with drug manufacturers.’

No comments yet