Approval rates rise to their highest level in a decade but hide a worrying fall in the number of applications

The UK’s largest physical sciences funding agency has experienced a significant decrease in the number of applications submitted in 2011–12, which has led to the highest grant success rates in the last decade. However, this may not necessarily be good news for the academic community.

Among the research councils, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) has made some of the toughest decisions when developing funding policies. In recent years, many of these have met with strong opposition and protests from the academic community, with some of the most controversial being the ‘shaping capability’ strategy, where specific research areas are prioritised, and blocking researchers who repeatedly fail to secure a grant from reapplying. The EPSRC has defended these strategies as a way to ensure the best science is funded within a shrinking budget. When policies are implemented, however, it is not always clear what the impact will be on the academic community. The recent publication of research proposal funding rates from 2011–12 now provides an indication.

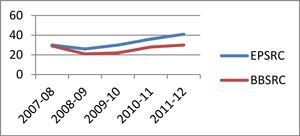

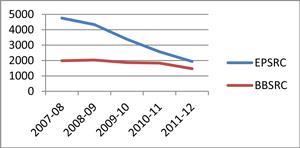

Between 1 April 2011 and 31 March 2012, the EPSRC sent fewer than 2000 grant proposals for peer review. Across the entire EPSRC portfolio the success rate was 41%. This increase will be welcome news for the council, which was concerned at the effectiveness of the peer review system when funding rates were low in 2009. Unfortunately, the high percentage of funded proposals is not due to more projects being funded but a consequence of a significant drop in the number of applications that were submitted by researchers. The academic community is roughly the same size, yet there was less than half of the number of proposals submitted in 2011–12 than in 2008–09.

Cloudy skies?

Paul Clarke, an organic chemist at the University of York, UK, is concerned by this outcome. ‘For investigator driven, blue skies research, applications are falling much faster than the money in the pot,’ he says. ‘This is due to the EPSRC demand management, also known as blacklisting, and the ban on resubmissions.’ When this trend is compared with activity in the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Councils (BBSRC), the contrast is palpable – the number of applications to the BBSRC has remained largely steady over the last five years.

The EPSRC says that it sees the fall in grant applications as a success, bringing demand to more manageable levels. A spokesperson for the research council says it considers success rates between 35% and 50% to be ideal, easing pressure on peer reviewers. She adds that the EPSRC has had a ‘very positive response from the community’ to its funding opportunities this year and the fall in applications is ‘the result of careful planning of submission timing’.

In 2011–12, there was an average of only 36 people who were constrained by ‘demand management’. While only a very small percentage of the academic community were prevented from submitting applications, the policy appears to have influenced behaviour. Chris Hayes, a chemist at the University of Nottingham, UK, says that the heavy-handed approach has caused many people to decide not to apply at all. ‘People are scared of being labelled a failure,’ he says.

Demand management may reduce the load on EPSRC staff and the peer review system, but it is unclear whether it increases the scientific excellence of the research that is funded. It has been suggested that it drives behaviour towards safe ideas and discourages adventurous bids. The European Research Council (ERC) is a growing funding source for blue-skies research and with a clear remit to fund big, daring, high-risk science, many of the truly ground-breaking science proposals may be moving from Swindon to Brussels.

Wrong message

Hayes is worried about the message that these success rates and the demand management policy sends to ministers and the Treasury. ‘EPSRC are creating the impression that we are putting in lots of rubbish proposals – that’s just not true,’ he says. ‘We need EPSRC to be making the case that they need as much money as the MRC [Medical Research Council].’ He also points out that the success rates give an artificial impression of a low demand for money from researchers.

Stephen Clark, head of the school of chemistry at the University of Glasgow, UK, agrees. ‘It creates the illusion with the politicians that all is well and that demand is being met adequately, when in fact many excellent researchers are being starved of support to do first class research.’

In any case, these higher success rates may not continue into the immediate future. The EPSRC has a significantly lower budget for responsive mode grants awarded in 2013-14. There has also been a huge influx of grants in the last few months in response to a very clearly publicised encouragement to submit applications in time for the 2012-13 financial year, when there will be more money to allocate. This will likely have a large impact on success rates.

Jim Iley, executive director for science and education at the RSC, says: ‘The EPSRC’s shaping capability programme has been designed to manage the number of proposals submitted, and to increase the number of larger awards. So as the Shaping programme takes effect, one would expect to observe an increase in the success rate, and the EPSRC has indicated that success rates between 30 and 40% would be appropriate. So the 40% quoted aligns with this. But it is a real concern that the overall value of the proposals funded has fallen by £110 million since the 2010–2011 period (from £488 million) and that the amount per proposal has fallen from £535,000 to £470,000, despite an increased success rate. This goes to emphasise that it is essential for the science community to continue to lobby hard for additional research funding.’

No comments yet