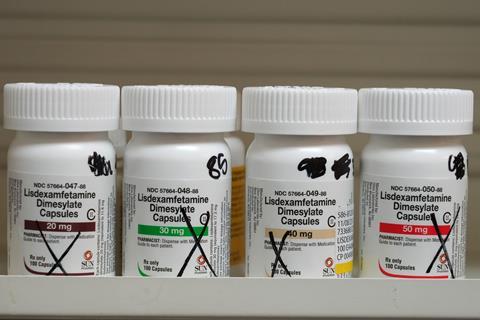

Drug shortages are a decades-old problem, but over the past few years they have hit record levels. A consistent stream of supply issues has disrupted supplies of vital medicines – from hormone replacement therapy (HRT), antibiotics and cancer chemotherapies, to medicines used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as the newest class of diabetes and weight-loss treatments.

Some of those shortages are now subsiding, as new supply routes come online, or quality issues are resolved. But some are more persistent. Some of the drugs on the US current shortages list have been there for almost a decade.

But what are the reasons behind these shortages and what is being done to ensure patients have continuous access to the medicines they need?

What is a drug shortage?

A drug shortage defines a period when the demand or projected demand for a drug exceeds the supply. Drug shortages can occur for many reasons, including manufacturing and quality problems, delays and discontinuation.

How much of a problem are drug shortages?

Medicines shortages can compromise patient care by delaying treatment or diverting patients to different, less suitable, drugs. They also put strain on pharmacy teams trying to source the products they need, and place economic burden on the healthcare system by spiking prices.

During the first quarter of 2024, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) – which actively monitors drug shortages in the US – alongside the University of Utah Drug Information Service, tracked an ‘all-time high’ of 323 active shortages, surpassing the previous record of 320 shortages in 2014.

The ASHP said most shortages involve low-cost generic drugs, particularly sterile injectables used in hospital treatments and procedures, such as baseline cancer therapies and intravenous antibiotics. Some of these medications have no alternatives, forcing hospitals and doctors to ration medication or even delay care.

The situation is no better in the UK. In November 2023, the British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA) trade body reported that medicines supply problems had reached record highs with a reported 100% increase in shortages of medicines between January 2022 and January 2024.

What’s more, the global nature of pharmaceutical supply chains means shortages are often interconnected, meaning that shortages in one country frequently impact on others.

Why do drug shortages happen?

Reasons are multifactorial – geopolitical factors such as Brexit, the Ukraine-Russia war and the Covid-19 pandemic have had a significant impact on supplies, as have soaring energy costs and inflation, logistical issues and the availability of raw ingredients.

One key reason for acute shortages is a sudden and unprecedented increase in demand, for example, due to a rapid increase in disease prevalence. In December 2022, an increase in cases of Strep A among children in the UK caused a surge in demand for penicillin, amoxicillin and azithromycin, particularly in solution, which resulted in shortages across the country and a significant increase in wholesale prices.

Emerging trends, such as the ‘Davina effect’ whereby an awareness campaign led by TV personality Davina McCall led to a sudden increase in demand for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in the UK can add further pressure to supply chains. Since 2022, Novo Nordisk has struggled to scale up manufacturing of Ozempic (semaglutide), to match public demand. Originally developed as a diabetes treatment, demand for the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist soared after clinical trials showed the drug could be used off-label as a weight-loss aid and it was promoted heavily by celebrities on social media.

Another reason for shortages is a sudden drop in supply. This might be because of recalls or quality problems – such as when Indian manufacturer Intas, the main supplier of cisplatin and carboplatin cancer chemotherapies to the US, failed a US Food and Drug Administration inspection last year, prompting a nationwide shortage. Or because a company takes a commercial decision to discontinue an unprofitable product, and there are insufficient alternative suppliers. However, drops in supply can also be the result of natural disasters – for example, in 2023, a tornado hit a Pfizer plant in Rocky Mount, US, destroying part of a large facility that manufacturers a quarter of the company’s sterile injectables for US hospitals.

Manufacturing problems, including shortages of raw materials or delivery mechanisms, issues with industrial capacity and flexibility and distribution or logistical problems, such as disruptions in international trade due to geopolitical conflict, can all contribute to shortages. Sterile injectables are particularly vulnerable to shortages compared to solid oral dose medications because of their expensive and more complex manufacturing processes.

The risk of drug shortages also increases because there is a geographic concentration of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing in China and India; two of the world’s largest producers of pharmaceuticals. In 2018, investigations identified traces of potentially carcinogenic nitrosamines in batches of the blood pressure medicine valsartan originating from a manufacturing plant in China, which was responsible for supplying API to multiple drugmakers around the world. The finding prompted a global recall from several manufacturers and sparked concerns for ongoing drug supplies.

However, the ASHP has said that the most severe and persistent shortages are driven by extreme price competition among generic manufacturers, which undermines investment in manufacturing capacity, quality assurance, and supply chain reliability and leads to a lack of incentives to produce less profitable drugs. As a result, lower-priced drugs are more likely to experience shortages.

What is the protocol when shortages happen?

Several countries have set up national reporting systems so that shortages can be communicated more easily. For, example, in the US, manufacturers can notify the FDA Drug Shortage Staff via a direct web portal, and the list is updated daily with new and resolved shortages, as well as additional information received from product suppliers regarding manufacturing capacity.

When a shortage occurs, the FDA works directly with the manufacturer of the drug to address the shortage and with other manufacturers to help ramp up production if they are willing to do so. In the case where a shortage cannot be resolved immediately and the shortage involves a critical drug needed for US patients, the FDA may look for a firm that is willing and able to redirect product into the US market to address a shortage.

In the UK, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) will liaise with medicines manufacturers, alternative suppliers and wholesalers to secure additional supplies; commission clinical advice from the NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service and national clinical experts regarding management options and alternative medicines; and contact medicines important to identify potential sources of medicines.

In October 2019, serious shortage protocols (SSPs) were introduced as part of preparations for a ‘no-deal’ Brexit to allow pharmacists to offer an alternative product specified in the protocol for items in short supply. Since then, the DHSC has issued 61 SSPs, with the number of active protocols peaking at nine in July and September 2022.

The UK government has also restricted the export and hoarding of some medicines where there is evidence, or risk, of a critical shortage which could adversely impact UK patients. This list is reviewed and updated regularly.

And, in 2020, the DHSC established the National Supply Disruption Response service to address supply problems affecting medicines and other products.

Regulators, such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, can also take a variety of regulatory actions such as speeding up the assessment process for new marketing authorisations; granting temporary exemptions from medicines labelling requirements so that medicines packaged for use in another country can be used; importing and testing batches of licensed medicines; and considering manufacturers’ requests to import unlicensed medicines for the treatment of individual patients. Other countries’ regulators have similar powers, but details vary.

What is being done to limit shortages?

In December 2023, the European Medicines Agency published a list of more than 200 critical medicines to avoid potential shortages – it deems a medicine critical according to two main criteria: the seriousness of the disease it targets and the availability of alternative medicines. The list is set to be expanded in 2024 and then updated every year.

At the end of April 2024, the EMA published recommendations to address vulnerabilities in the production and delivery of medicines included in the EU critical medicines list and strengthen their supply chains.

As part of these recommendations, suppliers in Europe may be asked to take on new measures such as stockpiling medicines; reviewing past shortages or back orders to help identify demand patterns; and increasing manufacturing capacity to avoid potential shortages of critical medicines in the supply chain.

There is currently limited transparency as to the actions of the DHSC in the UK regarding decisions affecting supply chains and it is unclear if the UK is following a similar system to the EU. In 2023, organisations representing UK pharmacists called for reforms to the systems used to manage shortages – for example to enable pharmacists to amend prescriptions to provide alternatives to patients when medicines are out of stock. But, in January 2024, the government indicated that it had no plans to introduce legislative proposals of this kind and would instead continue to rely on serious shortage protocols to enable pharmacists to amend prescriptions on a case-by-case basis.

In the US, many policy solutions have been offered, including stockpiles, and support for domestic and advanced manufacturing. The Biden administration has pushed to fund an increase in domestic manufacturing as a way to combat supply chain issues in pharmaceuticals, with measures taken in 2021 as well as this year to encourage more production capacity.

In April 2024, the US Department of Health and Human Services appointed a supply chain resilience and shortage coordinator to spearhead strengthening critical medical supply chains and related shortages.

And, in May, the US Senate Finance Committee drafted a bipartisan bill to mitigate shortages by having state healthcare provider Medicare pay bonuses to hospitals and physicians for contracting practices that ensure adequate supplies of drugs – starting with generic sterile injectables and infused medications, such as chemotherapies.

No comments yet