Chocolate seems to suppress the signal of the principal psychoactive component of marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and probably other cannabinoids as well, according to new research led by David Dawson, from the cannabis testing lab CW Analytical Laboratories in California. This indicates just how difficult it is to measure the potency of cannabis-infused edibles that are bombarding the marketplace in the US and elsewhere.

Dawson presented his research at the American Chemical Society’s national meeting in San Diego. ‘We noticed some kind of anecdotal variance in the potency values we would get for testing these chocolates, and it seemed a little peculiar so we wanted to investigate that,’ Dawson recounted. He noted that chocolate is one of the more difficult food matrices to test because it has high amounts of fats, polyphenols and tannins, creating ‘a veritable organic soup of compounds.’

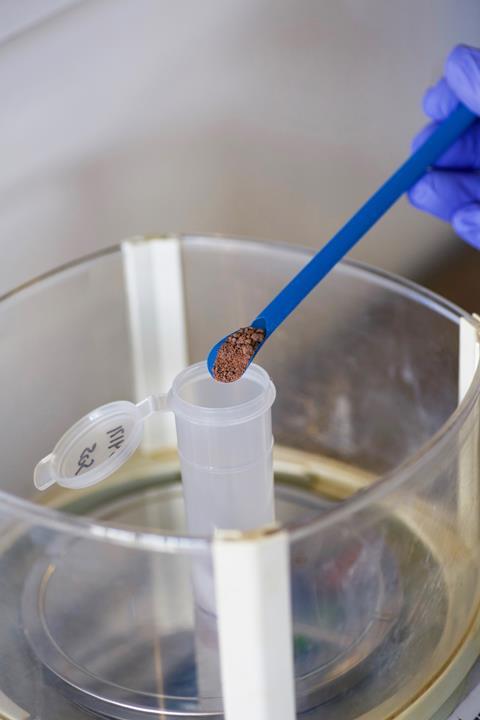

To research this issue, Dawson’s team ground up cannabis-infused chocolate bars from one particular producer into a fine powder, sonicated that in a solvent, centrifuged it, and then froze it, a process known as winterisation. Next, the researchers filtered samples and analysed them using high-performance liquid chromatography. The scientists then tested two samples – one that was 1g and another that was 2g, and they found that the 1g sample loadings consistently gave higher calculated potencies.

‘That is rather surprising, that definitely goes against what I would consider basic statistical representation of samples,’ Dawson recalled. ‘But it does seem here that we are actually getting less accurate and less precise data when we are prepping it with more chocolate in the vial.’

To rule out the possibility that incomplete extraction accounted for this odd phenomenon, the researchers took chocolate from the same producer that contained no cannabis, and they added it in 1, 2 and 3g amounts to a stock solution of THC. The team again observed decreased THC recovery with increased chocolate amount.

As an organic chemist by training, Dawson was anxious to figure out what molecular interactions were behind these unexpected results. He tried to tease that out by testing different chocolate products – specifically, cocoa powder, baking chocolate and white chocolate, which all contain different amounts of fat. Based in part on those results, his current hunch is that the fats are the culprit.

Beyond chocolate

‘When you are making edibles at home, you have to stew the cannabis flour in butter to extract the cannabinoids, because the cannabinoids have to go into the fats … and your body stores them in your fat,’ he explained. ‘So, it is not crazy to think that if you are providing a source of fat, such as this chocolate … then cannabinoids in solution are being attracted to the fats.’

The finding has implications beyond chocolate and THC. It is likely that an analogous phenomenon might be occurring with other cannabis-infused products like cookies, brownies, and even topicals, which are a kind of fatty emulsion product. ‘Any of the complex fat-based products may be having some effect similar to this,’ Dawson said. He also pointed out that if his fat hypothesis is correct, the same trend could probably be observed with all cannabinoids, including cannabidiol (CBD) – which is not psychoactive and is increasingly popular and ubiquitous in food, drink and cosmetic products – since they behave fairly similarly.

Despite being surprising and somewhat troublesome, the findings do not raise a public health concern. ‘At most you are getting 5% more cannabinoids than what’s listed on the label – I don’t think that is going to dramatically effect anyone,’ Dawson stated. ‘That is not going to put anyone in danger.’

However, these results do point to a significant potential problem for cannabis companies trying to bring products to market, and for the scientists trying to analyse them for potency and contamination.

It’s very frustrating not having any standardised methods

In California, for example, where cannabis is legal for medical and recreational use, the state regulations require that cannabis-based edible products test within 10% of their label claims. If they fall below that threshold, then every unit in the batch must be relabelled, and often the producers do this by hand. ‘That is a big financial hit, and it can make the product look not as good when it is important to establish a brand identity,’ Dawson explained.

The consequences are even more dire if tests suggest a product has more than 10% of the cannabinoids it claims to. In that case, it is deemed unfit for consumption in California and can’t be sold legally.

‘It is a signal suppression effect, so the actual chocolate bar might be 5% stronger than what the values are if this comes into play, so it might erroneously trigger a fail for the producers … when in fact that might just be an analytical quirk,’ Dawson explained. ‘That can traumatically effect their entire product lots.’

Kyle Boyar, a field application scientist at a cannabis testing lab in Massachusetts called Medical Genomics, agrees that fats are likely responsible for Dawson’s findings on chocolate interfering with potency data. ‘If you have more fats there present to bind up your cannabinoids then you are going to see little recovery, you are going to see less of them,’ he says.

However, Boyar suggests that by winterising their samples and thereby removing the lipids, Dawson’s team may have confounded their results. Nevertheless, he says the findings are important and go beyond chocolate to many more cannabis-infused products. Boyar also says that the results are not limited to THC, and probably extend to other cannabinoids like CBD, since they also often have a strong affinity for fat.

Julia Bramante, who chairs the American Chemical Society’s cannabis chemistry subdivision and is also a lead scientist at Colorado’s department of public health and environment, says that while this research is focused on THC, ‘these types of considerations are not unique to chocolate or potency testing and can be applied to many different cannabis products.’

She finds Dawson’s data both interesting and important, but emphasises that it was specific to his lab and his methods. ‘There very well could be other labs using other types of methods that aren’t encountering a similar phenomenon to what he is reporting,’ Bramante says.

Questions aside, the work highlights the need for reference standards in the cannabis field. ‘It’s very frustrating not having any standardised methods, or anything, from lab to lab and state to state,’ Dawson added. ‘It is still very much the early, primordial days of this for sure.’

No comments yet