Mars’s distinctive red hue has long been attributed to haematite, a rust-like iron mineral, formed under dry atmospheric conditions. New research now points to ferrihydrite, a hydrated iron oxide, that forms in aqueous conditions, challenging conventional beliefs and hinting at a wetter Martian past.1

Led by Adomas Valantinas, a planetary scientist at Brown University, US, a team of planetary scientists collated data from multiple Mars orbiters, rovers and used laboratory simulations to suggest that ferrihydrite could be widespread in Martian dust. ‘There was this idea that haematite is forming slowly by minimal, gas–solid interactions on the surface over billions of years, but we found ferrihydrite which needs brief interactions and rapid kinetics to form, requiring liquid water,’ explains Valantinas. ‘This told us that the ferrihydrite must have formed early on when there was liquid water. It’s not a modern product, but an ancient one.’

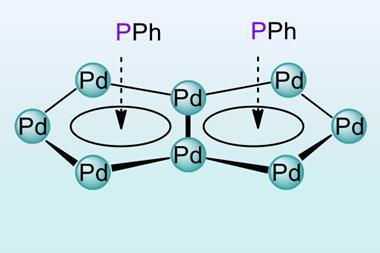

To test this hypothesis, the researchers replicated Martian dust in the lab using a mixture of ferrihydrite and basalt, a volcanic rock abundant on Mars. ‘I found them in the Azores, in these lava caves where there’s lots of basalt and water,’ says Valantinas. ‘I also found ferrihydrites in iron-rich streams along the east coast of the US.’ They then processed the rocks with a specialised grinder to match the nanometre-sized grains found on the planet and characterised them using x-ray diffraction and reflectance spectroscopy.

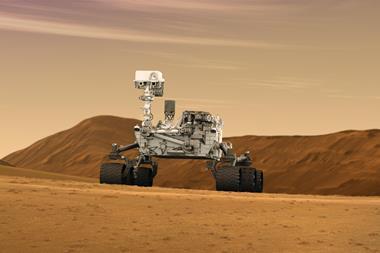

By cross-referencing the spectral fingerprints to surface-level measurements from rovers including Curiosity, Pathfinder and Opportunity, they found that ferrihydrite, rather than haematite, provided the best match. ‘The paper makes a strong case that the dust spectra align with laboratory ferrihydrite mixture spectra,’ says Eva Scheller, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, US, who was not involved in this work. ‘However, it seems unlikely that Martian dust can be reduced to one “single spectrum”, given the likelihood of natural variability.’ Scheller also notes that the data derived from the rovers is unlikely to capture the complexity of geological materials. ‘Dust on Mars, as on Earth, is generally a combination of multiple chemical components. Visible and infrared region analysis alone probably doesn’t provide enough data dimensions to fully resolve those mixtures,’ she explains. ‘Rover datasets fall into a similar category as Perseverance instrumentation, which is not really designed to parse out mineralogical information about Martian dust.’

The third set of experiments that they did were dehydration experiments. By simulating Martian conditions, they examined whether the ferrihydrite would crystallise into haematite. ‘But that was not the case,’ explains Valantinas. ‘We saw that not only was [the ferrihydrite] stable, it lost some water on the surface but didn’t lose the chemically bound water.’

Ancient water

The implications of these findings extend beyond colour. Ferrihydrite forms rapidly in cool water and is commonly found in Earth’s soils where water has flowed for short periods, such as in melting snowfields or after intense rainfall. Its presence across Mars may suggest that water persisted on the surface longer than once believed, aligning with a period of intense volcanic activity around three billion years ago, when interactions between water and lava may have created ideal conditions for ferrihydrite formation. These findings suggests that Mars’s surface oxidation occurred under cooler, water-rich conditions rather than the arid processes previously assumed.

These results dovetail with another collaborative study led by Guangyou Fang, a physicist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Michael Manga, at the University of California, Berkeley, US, which suggests the presence of a three-billion-year-old buried shoreline on Mars.2 Using China’s Zhurong rover to identify subsurface deposits in Utopia Planitia, a vast Martian plain linked to ancient oceans, they observed layers that were consistent with coastal sediments. Found at depths of 10 to 35 metres, these formations indicate the possibility of a stable, long-lasting ocean, rather than a short-lived melt, thereby potentially supporting the ferrihydrite hypothesis. ‘[The ferrihydrite study] complements the Zhurong results, and mine and others’ prior work showing evidence for an ancient ocean, by providing evidence for a widely wet early Mars,’ says Benjamin Cardenas, a sedimentologist at Pennsylvania State University, US and co-author of this study, who was not involved in the ferrihydrite work. ‘This is how real scientific understanding occurs – when several independent datasets begin aligning in their conclusions.’

Definitive confirmation of the compounds behind Mars’ iconic colour will have to wait until samples are brought back to Earth though. The Perseverance rover is currently collecting material for a future sample-return mission. ‘We cannot always view planetary phenomena through Earth’s kind of knowledge,’ says Valantinas. ‘Having the Martian dust samples would provide important information on how minerals evolve under conditions dramatically different from that of Earth’s, filling critical gaps in our understanding of planetary surface evolution.’

References

1 A Valantinas et al, Nat. Commun., 2025, 16, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-56970-z

2 J Li et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2025, 9, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2422213122

No comments yet