Our roundup of another tough year for the pharma industry takes a closer look at the big players hit by big fines

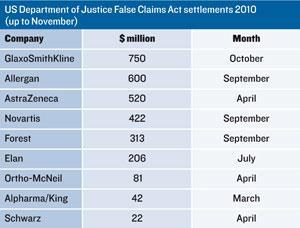

It was another tough year for the pharma industry, with downsizing, pricing concerns and the impending expiry of patents on many big-selling products all having an impact. But some of the biggest headlines were caused by eye-watering fines dished out in the US for, in most cases, violations of the False Claims Act through off-label marketing - promoting medicines for indications they haven’t been approved for.

Scrutiny of the industry’s commercial practices has increased in recent years, leading to a big rise in investigations for fraud and abuse in claims for reimbursement under government-funded health insurance programmes, such as Medicare. In 2009, Pfizer faced the largest ever corporate fine of $2.3 billion (?1.5 billion). Nothing in 2010 came close to that, but there was no shortage of big payouts. Allergan, for example, was fined $600 million for off-label promotion of Botox, AstraZeneca $520 million over antipsychotic Seroquel (quetiapine), and Novartis $422 million over antiepileptic Trileptal (oxcarbazepine).

Tactics companies were charged with included: ghost-writing scientific papers; promoting drugs to physicians working with patient groups the drugs weren’t approved to treat; and even creating sham consultancies that enabled them to pay physicians to attend what were little more than marketing presentations. Meanwhile, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) was fined $750 million for selling a range of substandard drugs manufactured in the early 2000s at its plant in Cidra, Puerto Rico.

This rise is in large part a result of the US whistleblower rules that protect those who bring corporate misbehaviour to the attention of the authorities. Not only do they gain protection from retaliation, they can also earn a slice of any resulting fines. In the GSK case, the quality control manager who reported the problem was awarded almost $100 million.

Howard Dorfman, counsel in the life sciences practice at US law firm Ropes & Gray, believes more cases are inevitable. ’There is a continuing interest in rooting out fraud and abuse within the healthcare industry,’ he says. ’The Department of Justice has already signalled its intention to continue its vigorous investigation activities. When you consider the increasing focus on patient safety related to off-label drug use, I think these investigations will continue and even, perhaps, escalate.’

And more investigations could lead to stricter rules. Fines are more than just a financial burden - they have a negative effect on consumers who are already dubious about the industry’s integrity. And this, Dorfman believes, could lead to companies facing increased legislation. ’Whether the industry has been successful in communicating its commitment to transparency, integrity and stopping inappropriate marketing practices is ultimately for the public to decide,’ he says. ’But public image is definitely a concern, and both companies and trade organisations are spending considerable amounts of time and effort addressing it.’

There has been debate in the US about whether these fines are sufficiently large to ’send a message’ to the industry, he says. ’I certainly think these amounts are extraordinary, and it’s somewhat simplistic to suggest they don’t have an impact on companies. They certainly get the attention of company executives. But because of the perception by some people outside the industry that the fines have not brought these practices to an end, there is increasing speculation that criminal prosecutions will be brought against employees in positions of authority.’ Indeed, this is already happening. At the end of November, a former GSK in-house lawyer was charged with obstruction and making false statements. This is unlikely to be the last such prosecution.

And now the companies are facing scrutiny on another front - the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which oversees the financial markets, is working much more closely with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) due to concerns that information about product development, adverse events and clinical trials is not being disclosed sufficiently quickly. ’The SEC wants to ensure information important to the investment community or the general public is provided in a timely and public way,’ Dorfman says. The SEC has even been mandated by Congress to set up a whistleblower programme, expected to be put into effect in the spring, and it’s likely that even more investigations and prosecutions will appear as a result.

Problems abound

The fallout from the 2009 swine flu pandemic was another source of critical headlines. After the World Health Organization (WHO), perhaps prematurely, declared H1N1 a pandemic, the pressure was on for pharma companies to develop and manufacture a preventative vaccine, and governments around the world put in huge orders. Yet the pandemic didn’t lead to all that had been feared, leaving big stocks of unused vaccine. A report for the Council of Europe declared that public health priorities were distorted by the WHO, which vastly overestimated the seriousness of the pandemic. Meanwhile, scientists advising the WHO had done paid work for pharma companies standing to gain from vaccine sales, it asserted.

Safety issues remain a concern, and it’s looking like the end of the line for one of the most controversial medicines of recent years, GSK’s antidiabetic Avandia (rosiglitazone). The drug has been under a cloud because of its potential to cause cardiac side-effects: it has been withdrawn in Europe, and while it remains on the market in the US, the FDA has severely restricted its use. GSK has already settled in more than 10,000 patient lawsuits, and more are ongoing.

Mergers activity slows

In recent years, the pharma industry has engaged in a lot of mergers and acquisitions. In 2009, for example, Pfizer bought Wyeth, Merck & Co bought Schering-Plough and Roche bought Genentech. But 2010 brought us only small deals and the Sanofi-Aventis $18.5 billion hostile bid for Genzyme, which has yet to reach a conclusion. Is this an end to the pharma ’mega-merger’? Unlikely, says Kevin Bottomley, senior principal at consultancy PharmaVentures: ’Everyone has been hugely cautious, and there has been little access to debt financing in the current economic situation.’

Another trend he identifies is a growth in large pharma companies divesting chemistry assets, particularly in the manufacturing arena. ’Products are divested, and the manufacturing assets go with them,’ he says. ’These tend to be products that the big companies see as non-core - those that have gone off patent, where they still own the brand name but generic competition means there is little marketing support.’

The patent ’cliff’, where many big-selling products will be opened up to generic competition, is looming ever closer, and Bottomley believes this may lead to the divestiture of numerous products that were once big sellers. ’In the old days, once it had been made by big pharma they continued to make it, but now some companies are even going as far as viewing the whole concept of manufacturing as non-core.’

Those looming patent expiries are a big driver for companies to cut costs. The fallout from last year’s mega-mergers is continuing to hurt, with Merck & Co, for example, intending to close several European research sites. Even those that haven’t merged are seeing the falling axe as a way to increase their bottom line by reducing their outgoings. AstraZeneca, for example, announced it will close its research sites at Charnwood, UK, and Lund in Sweden.

The need to cut costs is also being fuelled by an ever-growing pressure on prices, particularly in the Eurozone, coupled with a weakness in research pipelines. ’I think we will see the large shake-outs continue,’ Bottomley says. ’Roche, which we take as a bellwether for a company that is doing well at the moment, is cutting costs quite severely. And even Novartis, which has said it isn’t making big cuts, is no longer making the major investments it was.’

He believes these trends will continue in 2011, along with a return to intense merger and acquisition activity. ’When they’ve gone through all this, what will the industry look like?’ he asks. ’I think big pharma will be leaner and more focused. Clearly there is still a need for innovation and the medicinal chemists who are looking for new drugs, but companies will look to be more cost-efficient. I also think there will be more externalisation of manufacturing - a trend that has been going on for years and is certain to continue.’

However, the number of diseases and populations that remain in need of drug treatment gives hope for the industry’s future, as Eddie Gray, president of pharmaceuticals at GSK, told the Financial Times Pharma & Biotech Conference in early December. ’I remain an optimist for the pharma industry, though not necessarily the one we have now,’ he said. ’Whether it’s in the developing world, or the demographics of ageing in the developed world, demand for unmet need will remain high.’

Sarah Houlton

Also of interest

No comments yet