Glassy gel superpolymer is sticky and can self-heal but is also hard yet stretchy

New class of polymer owes its properties to ionic liquid solvent

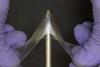

A new class of polymer that is transparent and hard like plexiglass but also stretchy with adhesive, self-healing, shape-memory and electrically-conducting properties has been created. Dubbed ‘glassy gels’, the material, which contains an ionic liquid solvent, could open up a wide variety of applications, possibly including batteries.

Glassy polymers, as the name suggests, are hard, stiff and brittle, and used to make many products, including water bottles or windows. By contrast, hydrogels are polymers swollen with water, which makes them soft and stretchy. Other kinds of soft polymer gels called ionogels have been made before with ionic liquids, which have been explored for their electrical conductivity.

Tinkering with such ionogels has led to a group of researchers stumbling upon an unusual new material that combines the properties of both glassy and gel polymers, essentially making them hard and stretchy. ‘This is really a story of curiosity and drive by the student in my lab, Miaxing Wang, who led the work – she deserves all the credit,’ says Michael Dickey at North Carolina State University, US.