Technique offers way to add electronic best before tags to food

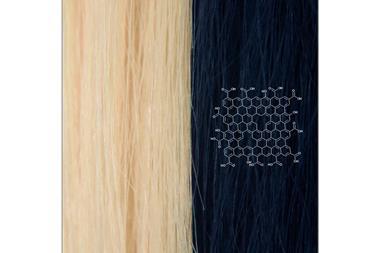

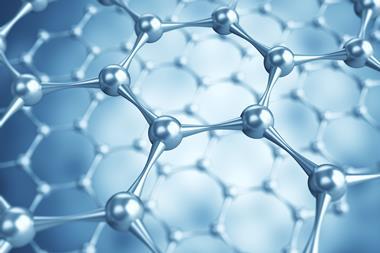

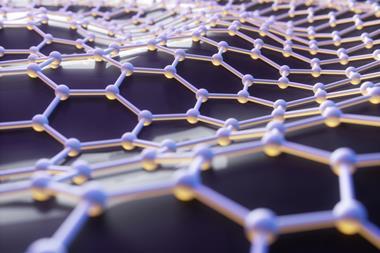

A group of researchers who previously demonstrated that graphene can be made out of chocolate, dead insects and even dog excrement has now used lasers to burn the 2D material onto toast. The team claim the method could be used to embed electronic tags or sensors directly in food sources, as the graphene that is produced is conductive and antimicrobial.

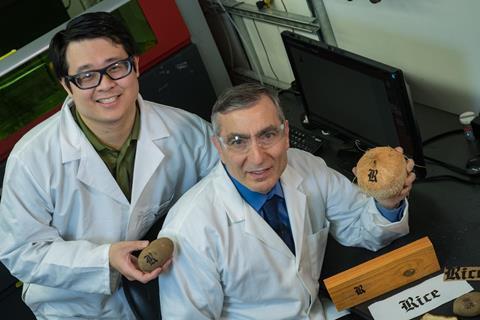

‘Sensors [could be] embedded to know if the food harbours E coli. Or to tell you whether it had ever been without refrigeration, for example,’ says James Tour from Rice University in the US. His group first demonstrated the production of ‘laser-induced graphene’ – a network of 2D graphene flakes that is produced by exposing carbon-rich materials to laser pulses – in 2012.

‘We use a technique that first converts the material into amorphous carbon – like burned toast or burned carbon – by a first laser pulse, and then a second and third pulse convert the newly formed amorphous carbon into laser-induced graphene,’ says Tour. ‘The entire process takes a millisecond. We do this by defocusing the laser so that there are overlapping spots as it rides along, and the overlaps are equivalent to multiple laser pulses.’

The team showed that the technique could be used to draw very precise patterns of graphene on food items. They reproduced the intricate ‘R’ that forms part of the Rice University logo on a piece of bread as a proof of concept. They found it worked particularly well with products rich in the woody material lignin, such as cork, coconut shells and the skin of a potato.

‘We can also form electronics on clothing for sensors or on paper for electronic paper,’ says Tour. He adds that the group plan to commercialise the tech, but are first focusing on other applications of laser-induced graphene such as films that kill microbes for water purification.

‘This is a very quick and easy way to make graphene on ubiquitous substrates and demonstrates a quick and cheap application of graphene for food quality checks and labelling,’ comments Felice Torrisi from the Cambridge Graphene Centre at the University of Cambridge in the UK. He adds, however, that commercial applications are still a long way off. ‘Several tests have to be run in order to understand whether there are effects on the quality of the food or human health.’

References

Y Chyan et al, ACS Nano, 2018, DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08539

1 Reader's comment