Environmentally friendly pyrotechnic cuts out the perchlorates by replacing them with copper iodide

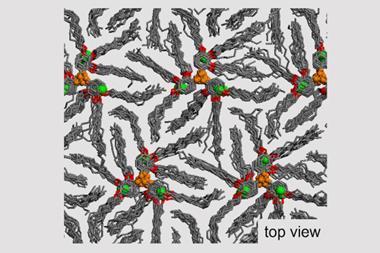

Blue flames are normally obtained by using copper or copper-containing compounds in the presence of a chlorine source, which produces the blue-emitting species copper(I) chloride. Sabatini from the US Army’s Picatinny Arsenal alongside Klapötke and Rusan from Ludwig Maximilian University, replaced the toxic copper(I) chloride in blue flares with the environmentally-benign copper(I) iodide.

‘Common sources of chloride include ammonium perchlorate, potassium perchlorate and chlorine donors such as poly(vinyl) chloride,’ says Rusan. ‘Unfortunately, perchlorates have toxicity issues. They interfere with proper thyroid gland functioning.’ Chlorinated organics, such as PVC, produce polychlorinated biphenyls, polychlorinated dibenzodioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans, which are highly carcinogenic, she adds. Since pyrotechnic mixtures rarely undergo complete combustion, unconsumed quantities of perchlorate in fireworks or flares can contaminate groundwater, and the US Environmental Protection Agency has established a 15ppb limit for perchlorates in drinking water. This has led to a sharp reduction in the amount of perchlorate-containing pyrotechnic items that can be used on some US military training ranges.

‘It was always believed that such a problem could never be avoided because copper(I) chloride was perceived as the only blue light emitter,’ says Rusan. But they used copper iodate to generate copper iodide, which they found was an effective blue light emitter. ‘Perchlorates are avoided altogether and no chlorinated organics are needed, so the result is a “greener” formulation,’ Rusan adds.

‘The team has achieved quite a highly saturated blue flame using copper(I) iodide as a novel blue light emitter,’ says Ernst-Christian Koch, who looked at the use of ytterbium in infrared decoy flares and discovered that they burn with a deeper green flame than barium chloride when he was at the University of Kaiserslautern, Germany. Koch, now at the centre for defence chemistry at Cranfield University in the UK, adds that one current problem with copper iodate is its price – €30000 (£2370)/kg – but future research could find cheaper ways to make copper iodide, for example using less pricey iodine sources.

The next step for Sabatini, Klapötke and Rusan is to scale up the copper(I) iodide-based blue light-emitting formulations. ‘This will be an important and necessary step if the technology is to find practical use in military and civilian pyrotechnics,’ concludes Rusan.

No comments yet