New boss Emma Walmsley outlines sweeping changes in order to focus on high-return drug projects

Priorities are shifting throughout UK pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline as it closes manufacturing sites and exits research projects in order to boost the prospects of other future drugs. Steered by Emma Walmsley, who took over as chief executive in April, GSK’s pharmaceuticals, vaccines and consumer health business areas are all changing direction.

GSK’s moves include terminating, partnering or divesting more than 30 pre-clinical and clinical drug development programmes. The most advanced of these is GSK’s withdrawal from a collaboration with Janssen Biologics on rheumatoid arthritis drug sirukumab.

The company is also reviewing already-approved drugs and considering selling their commercial rights. These include rare disease products such as Strimvelis, the gene therapy reported to have a £530,000 price tag, only used to treat two patients so far. GSK will stop making type 2 diabetes drug Tanzeum (albiglutide) and consider selling its cephalosporin antibiotic activities, including their manufacturing facilities. ‘In the next 12 months we expect to divest or exit more than 130 non-core tail brands in pharma alone,’ Walmsley told investors and analysts.

This ‘portfolio simplification’ aims to generate £1 billion in cost savings to fuel future growth, mainly through what Walmsley called ‘efficiency in our supply chain’. As part of this, GSK plans to close nine manufacturing sites, including the Slough, UK, plant that produces powdered hot drink Horlicks, which the company is selling. It has also scrapped a plan to build a £350 million biopharmaceutical plant in Ulverston, Cumbria. Job losses in Slough, and also at the company’s Worthing site, will total over 300 out of 5000 UK manufacturing jobs.

Insufficient resources

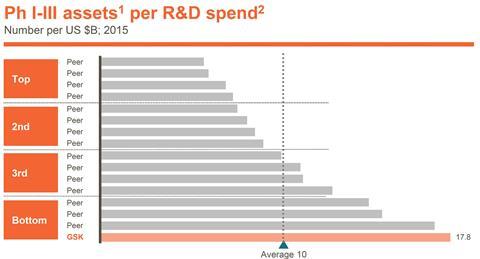

Walmsley hopes that the changes will improve GSK’s pharmaceutical R&D performance, even though the company has been an industry leader in numbers of drugs launched. ‘Peak year sales for these assets have been amongst the lowest of our peer group, so we have not consistently translated the output into commercial success,’ she underlined.

The problems are partly the choice of drugs developed, and partly how they’ve been marketed. Consequently GSK will now integrate its commercial and R&D activities more closely. But Walmsley also stressed that GSK has spent far less per project than its rivals. ‘We arguably didn’t back some key assets with sufficient resources to get strong enough data packages,’ she said.

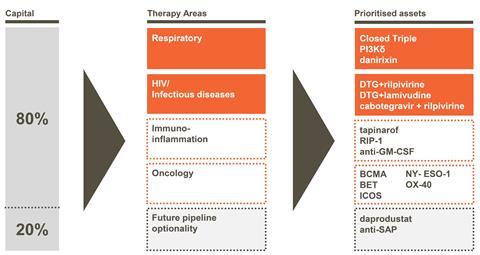

Therefore GSK is focussing 80% of its pharmaceutical R&D activities on four areas of research. Two are current areas of strength, respiratory and HIV/infectious diseases, including new antibiotics. The other two are oncology, whose discovery capabilities the company retained after trading its cancer drug portfolio to its Swiss rival Novartis in 2014, and immuno-inflammation. Where the remaining 20% of GSK’s pharmaceutical R&D work will focus remains underdetermined.

‘The decisions announced last week are about prioritising R&D spend, not cutting it, and our intention is to redeploy staff to support priority projects wherever possible,’ says a GSK spokesperson. ‘To support our future pipeline we will continue to have a broad discovery organisation.’

In the short term, GSK is focussed on launching Shingrix, a potential new shingles vaccine, its ‘closed triple’ 3-in-1 respiratory medicine, and dolutegravir and rilpivirine as an HIV combination treatment. Patrick Vallance, GSK’s president, R&D, also emphasised the chemistry platforms the company can use to discover new drugs. These include proteolysis-targeting chimeric molecules, or PROTACs, which can selectively tag disease-associated proteins. Vallance also emphasised the company’s DNA-encoded screening libraries, large collections from which biologically active molecules can be identified through their DNA tags. Additionally, the company intends to use genetic know-how gained from Strimvelis in manufacturing new cancer drugs.

Preparing for pressure

The changes are motivated by shareholder returns under predecessor Sir Andrew Witty that Walmsley described as ‘uncompetitive’. GSK’s sales growth has been hampered by slow or failed product launches, she said, even as prices of GSK’s existing drugs are coming under pressure.

One threat comes because GSK’s largest product, the combination fluticasone/salmeterol asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatment called Advair, is now facing competition from generic rivals. And in the US, politicians are aiming to cut healthcare spending, while supply issues have hampered sales of products like Menveo, GSK’s meningitis vaccine.

Ali Al-Bazergan, lead analyst at Datamonitor Healthcare in London, calls the moves ‘largely positive’. He notes the shift to focus on the company’s leading pharmaceutical areas follows the example of other leading drug makers. He adds that the focus on cancer makes sense because companies are being forced to collaborate on immuno-oncology technology. ‘This will hold GSK in good stead as its assets move through the development pathway,’ Al-Bazergan says.

No comments yet