Reducing environmental pollution and tackling quality issues to stave off resistance

For as long as we have had antibiotics, scientists have been aware of the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). As Alexander Fleming, the discoverer of penicillin, received the Nobel prize for physiology or medicine in 1945, he highlighted the need to avoid exposing microbes to the drug in ways that could ‘educate them’ to resist the drug: ‘The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself, and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant.’

Alongside crucial efforts to develop new drugs, with new modes of action that can overcome resistance mechanisms, and developing the commercial frameworks that will see companies encouraged to invest in commercialising these new drugs, it is vital that industry, governments and society take steps to protect and conserve the antibiotics that are already available, to stave off the threat of resistance for as long as possible.

Responsible stewardship of existing and future antibiotics is a complex and multi-factored problem. There are aspects that lie with governments and regulators – such as implementing and enforcing policies on how drugs are allowed to be sold and used – and there are aspects that lie more with industry, for example controlling environmental pollution containing active drug ingredients. But there is also a societal responsibility to change the culture and expectations around how crucial drugs are used and prescribed.

Exposure control

India, along with China, is one of the top producers of generic medicines, including antibiotics, for both indigenous and global populations. India also exemplifies various contributions to the global AMR problem, which are echoed to varying degrees in countries across the globe.

As in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), antibiotics are readily available over-the-counter in local pharmacies throughout India – with no need of doctor’s prescription. Hence there is a large amount of unregulated consumption of antibiotics, meaning people can end up using the wrong type of drugs, or the wrong dosages and incomplete courses. All of which can accelerate resistance.

Hundreds of fixed dose combinations (FDCs) of antibiotics are also available in India and elsewhere. These formulations contain a fixed ratio of two or more drugs in a single tablet. While some have been created to address specific medical needs, many others are developed to get around patent and intellectual property issues, or for commercial reasons to increase profitability. These may contain combinations of antibiotics that make no medical sense – for example working no better than the individual drugs – and are potentially harmful. They also contribute strongly to producing strains of bacteria that can resist multiple different antibiotics. Large numbers of the FDCs available in India were originally approved by state-level regulators rather than India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organization.

The Indian government has made multiple attempts to curtail use of various FDCs, including many antibiotics. An initial ban of 344 products in 2016 was overturned by an appeal from manufacturers in 2017. In late 2018, the government again moved to ban over 300 FDCs, including 26 antimicrobials, but faced significant challenge from manufacturers. In 2022, a team from Washington University in St Louis, US, published analysis of sales data for antimicrobial FDCs before and after the ban. They concluded that, while overall sales of the banned FDCs had reduced significantly, several continued to be sold in significant volumes. Sales of other, non-banned combinations of the same and related drugs also increased, offsetting the effect of the ban.

Overuse and abuse of antibiotics is a universal issue. Across European countries and the US, for example, various estimates suggest around 20-30% of antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary – usually for viral respiratory conditions. While policies in recent years have seen these number decline, they remain a significant contributor to resistance pathways.

Pollution needs a solution

However, bacteria are not only exposed to antibiotics when they are administered as medicine. If wastewater from manufacturing is allowed to pollute the environment, either through direct discharge from manufacturing plants, or through ineffective wastewater treatment, exposed bacteria can very rapidly develop resistance.

In 2017, researchers from Leipzig University Hospital in Germany analysed antibiotic pollution in Hyderabad, south India, where 30% of India’s drugs for export are manufactured. The team took samples from close to drug manufacturing facilities, sewers in the Patancheru-Bollaram industrial area, two sewage treatment plants, the Musi river, and habitats in Hyderabad and nearby villages. Almost all the samples contained bacteria resistant to multiple drugs, and many were contaminated with ‘excessively high concentrations’ of antibiotics and antifungals.

‘Ground water pollution leading to chronic diseases around manufacturing facilities that do not comply with pollution control guidelines is a long-standing issue in India,’ says Dinesh Thakur, whistleblower and co-author of ‘The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India’ – a book that investigates various issues within the Indian drug industry and regulatory agencies. ‘The Pollution Control Boards are at best incompetent, and at worst, colluding with the industry with little regard for the long-term health effects of their actions,’ he says.

Parts of the industry have begun to address environmental pollution. Some larger companies such as Mylan are implementing ‘zero liquid discharge’ technology at their plants, whereby all wastewater is treated and recycled within the confines of the plant.

In June 2022, the Geneva, Switzerland-based AMR Industry Alliance (AMRIA) – a life sciences industry coalition – and the British Standards Institution (BSI) jointly released an Antibiotic Manufacturing Standard. The voluntary standard aims to provide clear guidance to manufacturers in the global antibiotic supply chain to ensure that antibiotics are made responsibly while helping to minimise the risk of AMR in the environment. It requires manufacturers have an effective environmental management system to ensure that their manufacturing activity will not have an adverse impact on the environment.

The AMRIA and BSI also offer independent certification based on the new standard. The certification will require an initial assessment, and then ongoing annual surveillance, to ensure that waste streams containing antibiotic active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and drug products are appropriately controlled during manufacturing by pharmaceutical producers.

However, it is too early to speculate on how many of the various small and medium Indian pharmaceutical companies would be willing to upgrade their infrastructure to get certified. And problems of contamination persist. In 2022, India’s independent National Green Tribunal (NGT) noted that the Balad, Sirsa and Sutlej rivers were being polluted with industrial effluents, including from dyeworks, electroplating plants and antibiotic production, from the Baddi industrial estate in the north Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. Wastewater from the site was being processed in a Common Effluent Treatment Plant that was not designed to neutralise active pharmaceutical ingredients, while a portion of the waste was being discharged directly into the river Sirsa.

The NGT also noted that there are, as yet, no specific standards set by the government of India for residual antibiotics in effluent from pharmaceutical manufacturing. The government set out draft standards in 2020, including proposed limits for wastewater. According to analysis presented to the NGT, the levels of ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin and azithromycin measured in effluents from at least two plants on the Baddi estate, both before treatment in the common effluent plant and afterwards in the effluent discharged into the river Sirsa, vastly exceeded those draft limits.

Quality is key

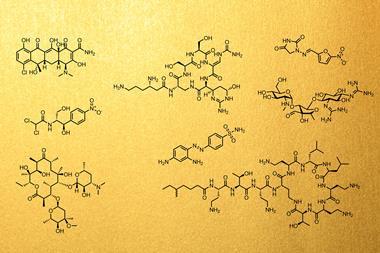

Pollution is not the only aspect of drug manufacturing that poses potential AMR risks. Lawyer Prashant Reddy, co-author with Thakur of The Truth Pill, highlights that drugs that do not meet quality thresholds – for example if they do not contain sufficient of the required active ingredient – are also a significant problem. However, he acknowledges that it is legally difficult to prove the link between substandard drugs and specific instances of resistance developing.

‘Substandard medicines are the biggest problem. It starts from manufacturing, flows through all supply chains and ends in pharmacies,’ Reddy says. ‘If the drug being administered is substandard, it is likely to lead to failure and the pathogens in the body will not be fully eliminated. So, quality of medicines remains a critical issue,’ he explains.

He suggests the Indian government has focused on promoting the growth of the pharmaceutical industry, for example through providing financial incentives and opening pharmaceutical parks, rather than focusing on tackling quality issues. The industry has expanded considerably, and exports continue to grow, he points out. ‘Most developing countries are going to find it difficult to find alternatives at similar prices to Indian-manufactured drugs, so they will continue to buy substandard medicines and the situation could get worse,’ he says.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1 in 10 medicines in low- and middle-income countries could be classed as substandard or falsified (meaning deliberately or fraudulently misrepresenting their identity – and likely to contain either no active ingredient, the wrong amount or the wrong ingredients altogether). Antibiotics and antimalarials are the most commonly reported substandard and falsified medicines, meaning they have significant potential to add to problems of resistance. The WHO stresses that falsified medicines infiltrate all countries worldwide, driven by unregulated internet distribution, but LMICs bear the brunt of the problem.

Distribution of substandard medicines thrives where access to high quality medicines is limited, and governance and oversight is poor. Therefore, measures that weaken the powers of regulators and governments to enforce quality standards could have knock-on effects in terms of AMR. The Indian parliament passed the Jan Vishwas (Amendment of Provisions) Act 2023. Aimed at increasing ease of doing business, this overarching law decriminalises certain offences, amending 183 provisions of 42 different existing acts or laws – including the Drugs and Cosmetics Act and the Environment Protection Act.

The amendments make court prosecution unnecessary, while also removing imprisonment as a punishment for many offences. For example, those found producing ‘not of standard quality’ or substandard drugs will now attract only a fine of ₹20,000 (£189) rather than the previous prison term of up to two years.

Governments, non-government organisations, pharmaceutical firms and trade groups have made various plans and commitments to try and address different aspects of the AMR issue. Many of those efforts have seen some degree of success. But plans are only successful if they are implemented, as Thakur points out. India, for example, formulated a National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance in 2017, but ‘as far as I know, nothing has been done’, he says tersely.

No comments yet