Bench scientists go through a lot of disposable plastics in the lab. Most end up in landfill, but there is a growing recognition that more can be done to recycle plastic research waste. A lab glove recycling movement is one way to tackle the problem and it has been gaining momentum across research universities in the US, often driven by young graduate students for whom making chemistry greener is a priority.

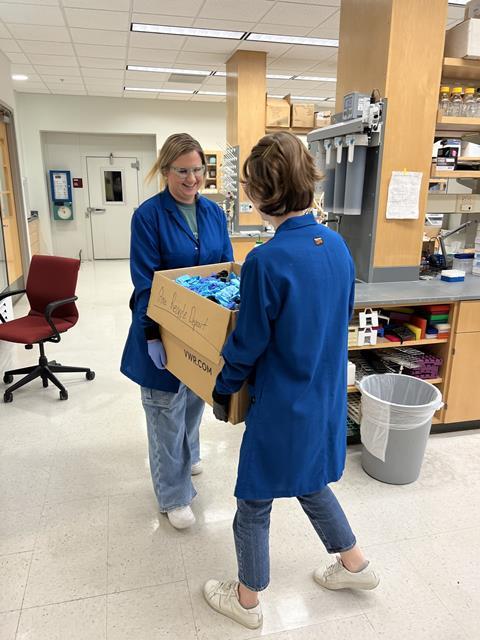

A couple of years ago, two PhD students in Florida State University’s (FSU’s) chemistry and biochemistry department – Kristen Weeks and Carley Reid – noticed just how many gloves were being thrown out in their department’s labs and decided to launch a recycling programme at their university.

The results of their initial survey in the summer of 2021 were startling. They found that labs in their department – about 150 graduate students and 30 research groups – were using an average of 15,600 pairs of gloves each month.

The duo brought the data to a faculty meeting in September 2021. ‘We said, “Here’s the number of gloves that we are using and throwing in the trash each month – it’s a staggering amount,” and we pitched this idea of the glove recycling project to the department to assess the interest,’ Reid recounts.

Next, they applied for and received an FSU Green Fund grant worth $5000 (£4069) to set up the program. Money in hand, they decided to recycle the gloves through TerraCycle, and then went lab-to-lab raising awareness about the programme. They recycled 88kg of gloves in their first year.

If you want your lab to cut the number of gloves going to landfill then those who’ve done it recommend that you start by quantifying the problem – how many gloves does your lab or department throw out every month? The second step is to apply for funding such as through university sustainability programmes.

Pitching your proposal to your department or research group is also key. Careful record-keeping of gloves collected and recycled is recommended too. Although it is extra work upfront, having numbers to show your impact is critical when making the case for the programme.

You’ll need to make friends with the university’s environmental health and safety department as well. This is to inform them about the processes that will be used to collect, store and ship the used gloves. ‘It is important to communicate with environmental health and safety to make sure that you’re doing everything safely,’ Reid explains.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, you need the researchers on board. ‘You have to get buy-in from all of the individual researchers, because it’s a new waste stream,’ says Bre Duffy, who established a glove recycling initiative at Tufts University in Massachusetts while earning her PhD. ‘They already have to think about gloves going into three different bins – trash, biohazard and chemical hazard – but now there is a fourth bin that they might go into for recycling.’

Advice from the trenches

‘They were obviously and understandably concerned about a new disposal stream – there were obvious potential risks, where someone could put something in recycling that should have gone into biohazard or chemical hazard bins,’ Duffy notes.

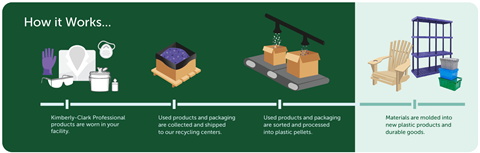

After looking into all the options, she decided to recycle with Kimberly-Clark’s RightCycle programme because it was offering to reimburse shipping costs if her department switched to the firm’s gloves.

The goal was to pilot this initiative in Tufts’s Chemical and Biological Engineering department and then expand it throughout the university if it was a success. But it ran for less than a year-and-a-half as Kimberly-Clark’s recyclable gloves became too expensive during the pandemic.

Suzy Gustafson, manager for the chemistry department’s procurement office at Purdue University in Indiana, helped launch the school’s highly successful glove recycling programme in 2014. At last count, she says it has diverted almost 17 tonnes of gloves from landfill.

Several similar programmes have been introduced at research institutions across the US and beyond, including in Europe. These generally all follow a similar model whereby a glove recycling company is selected, which then provides collection boxes for labs. These are then picked up regularly and transferred into larger boxes. Once a shipment is ready to go out, the company in charge of recycling is notified and the package is sent out. Some of these firms accept only their own gloves for recycling, but others will take those that are nitrile, latex, vinyl and lightly contaminated, provided they are made safe by a process such as autoclaving.

Downcycled and donated

These materials are not turned into new gloves, however. They are typically processed into plastic pellets and transformed into other products like chairs, shelving units and outdoor furniture.

Once a programme is running, it is also crucial to plan how to keep it funded. At FSU, the Green Fund grant is only supposed to kickstart novel sustainability projects. ‘Now what we’re really trying to work on is getting money for different departments who want to start their own glove recycling, or some kind of other recycling or sustainability project, and we want to have that money secured from FSU,’ Reid says. So far, she and Weeks have spent about $1300 of the original $5000 award.

Costs are highly dependent on the individual lab and the volume of gloves sent for recycling, but Rachel Schoeppner, a cleanroom facility manager for the California Nanosystems Institute (CNSI) at UC Santa Barbara, estimates the figure at around $20 a month for a standard lab and significantly more for a larger facility. ‘I am looking at around $10,000 per year for around 30 participating labs just in boxes and labour hours,’ she says. Over the last year, Schoeppner estimates that the UC Santa Barbara initiative has recycled over a tonne of lab gloves.

Although gloves are one of the most ubiquitous examples of plastic waste in the lab, many other consumables could potentially be recycled too. These include pipette tips, plastic film and syringes. ‘Can you imagine how much we can divert [from the landfill]? There’s a lot that moves through these labs, especially the undergraduate labs,’ Gustafson says.

No comments yet