The destruction of the Kakhovka dam in Russian-occupied southern Ukraine exposed large quantities of heavy metals that pose a ‘largely overlooked’ threat to surrounding ecosystems. Researchers who analysed pollution associated with the dam’s destruction say that the protection of dams in military zones should be a priority concern given the potential long-term impact on both people and the environment.

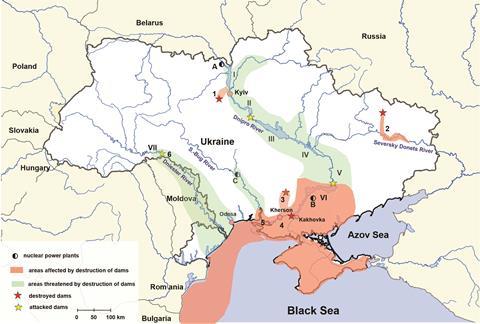

The Kakhovka dam, located upstream of the city of Kherson on the Dnipro river, collapsed in June 2023 following a suspected explosion. Ukraine and its allies have blamed Russia for blowing up the dam, while Russia has denied responsibility. The extensive flooding along the lower Dnipro River that followed resulted in thousands of people being evacuated from their homes and the deaths of at least 58 people.

While the economic and societal impacts of the dam’s collapse have been widely reported, assessments of the long-term environmental effects and threats to human health have been hindered by ongoing combat in the area.

Now, researchers have combined field surveys, remote sensing data and hydrodynamic modelling with insights from dam removal practices, flood hazard assessment and analysis of ecosystem reestablishment, to understand the scale of the catastrophe. The team also outlines possible approaches for reestablishing the damaged ecosystem.

‘When the disaster happened a lot of scientists were giving different opinions, and also a lot of myths emerged about what was happening there,’ explains Oleksandra Shumilova, a river scientist based at the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Berlin, Germany, who led the project. ‘The aim of our [research] was to [carry out] a scientifically based, comprehensive assessment of what was happening.’

The researchers found that destruction of the dam had resulted in substantial erosion, loss of vegetation, habitat destruction and the death of large quantities of fish and other organisms.

In addition, they revealed that before the dam collapsed, large quantities of pollutants from industrial and agricultural sources – including heavy metals, nitrogen and phosphorus – had accumulated in a thick layer of sediment settled on the bottom of the reservoir.

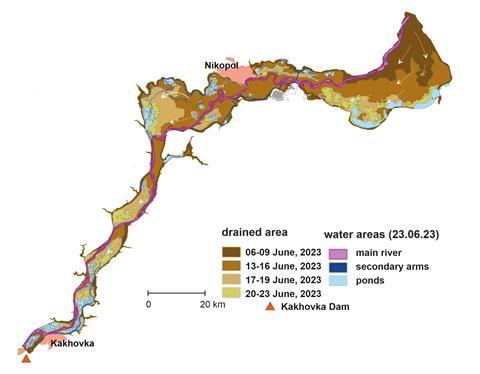

The team’s models suggest that when the dam was breached, two waves produced a surge of water both up- and downstream, rapidly draining the reservoir and exposing as much as 1.7km3 of polluted sediment. The researchers estimate that this sediment contains up to 83,300 tonnes of highly toxic heavy metals, which they describe as a ‘toxic time bomb’.

Less than 1% of the pollution has likely been released into the surrounding areas so far, mostly from upstream of the dam, the researchers say. However, surface runoff during rainfall events and seasonal floods, such as those occurring in March 2024, will continue to mobilise the pollutants. Shumilova says that the threats posed by the release of these heavy metals – both ecological and to human health – have been overlooked.

‘There are different discussions going on but there is no mention of this issue at all,’ says Shumilova. ‘People argue that this area should be left to be colonised by vegetation, no one talks about how this vegetation will accumulate heavy metals, how it can pass through the foodweb [and] how it can affect human health.’

Overall, the researchers predict that reestablishment equivalent to 80% of an undammed ecosystem could be expected within five years and that biodiversity of the river environment will start to increase within two. They note that the heavy metal pollution could be mitigated by bioremediation methods – using plants to absorb the pollutants – and propose building two 15-kilometer-long barriers along the Dnipro to limit the spread.

‘Shumilova [and her colleagues] provide an unusually high-fidelity view of the environmental impacts of war,’ says Joshua Daskin, an expert on the impacts of war on the environment, who serves as director of conservation at the Archbold Biological Station in Florida, US.

‘Scientists, very understandably, don’t often work in the hottest conflict zones, making it hard to measure wars’ effects. The Kakhovka dam example, though, is just one case of the widespread decline in ecological conditions during and after wars and other periods of bureaucratic instability,’ he adds. ‘Government activities may be redirected from ecological concerns to military priorities during a conflict, and NGOs may be forced to withdraw program staff for safety reasons – both with often-negative impacts on wildlife and human communities.’

Update: This article was amended on 24 March 2025 to provide additional context on the destruction of the Kakhovka dam.

References

O Shumilova et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.adn8655

No comments yet