Scientists think they know why the standard kilogram has gained weight and a chemical peel could be the solution

UK scientists have developed a cleaning technique that could solve a long-standing puzzle in the field of metrology – how to return the standard kilogram, against which all others are measured, to its original mass.

The base unit of mass, the kilogram, is defined by the International Prototype Kilogram (IPK) – a cylinder of platinum and iridium that was cast in 1879 and stored in a vault in the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in Paris. Around 40 replicas were made and distributed around the world to use as a standard reference to produce weights and standardise mass. But following three periodic verifications, where copies were returned to Paris to check their mass against the original IPK, scientists discovered that their weights are drifting.

These tiny changes – which are less than 100µg – are thought to be the result of surface chemistry increasing their mass due to atmospheric mercury contamination and the growth of a carbonaceous layer. It is also possible that nitrogen trapped when the prototypes were cast has since leached out.

‘Mass is such a fundamental unit that even this very small change is significant and the impact of a slight variation on a global scale is absolutely huge,’ says Peter Cumpson, who is behind the new research at Newcastle University. ‘There are cases of international trade in high-value materials – or waste – where every last microgram must be accounted for.’

Although cleaning methods have since been implemented using alcohol and steam they require mechanical rubbing, thereby making it difficult to maintain consistency. Now Cumpson and his colleague Naoko Sano have tested a combined solvent wash and UV–ozone treatment on contaminated platinum and gold surfaces that requires no rubbing.

UV treatment

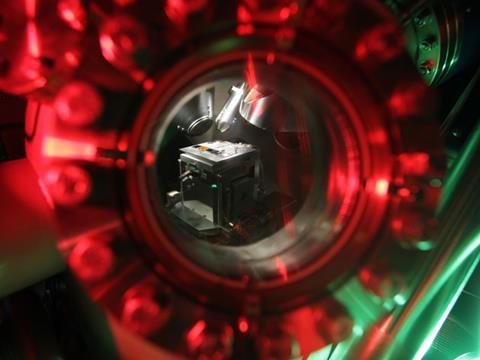

The team first contaminated platinum and gold foils with the common lubricating oil WD40. They then pre-washed the foils in methanol, followed by pure water to remove particulates and then exposed them to ozone gas – a technique used to clean semi-conductor surfaces. Finally, the samples were heated for 24 hours in filtered lab air to stabilise them.

Using a Theta-probe XPS machine they analysed the organic materials on the platinum and gold and found that their technique removed contamination without damaging the platinum or gold surfaces. Oxide was initially observed forming at the surface but ceased before it became a significant problem in terms of adding mass. Indeed, the team believe the oxide is likely to decompose slowly over time to metal and gaseous oxygen.

Stuart Davidson at the National Physics Laboratory in Teddington, UK, says the work offers ‘interesting additions to the UV–ozone cleaning process which NPL are currently evaluating with regard to cleaning primary (platinum–iridium) mass standards’. ‘The key advantage of UV cleaning is that it is non-contact and repeatable, provided parameters of UV intensity, exposure time and, to some extent, ozone concentration are controlled,’ he adds.

Defunct definition

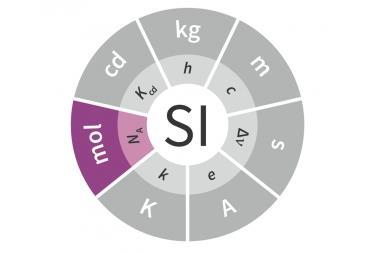

However, there is another solution on the cards to solve the kilogram’s weight problem. Delegates at the 24th General Conference on Weights and Measures held in 2011 voted for a change in the definition of the kilogram. The idea is to define it in relation to the mass of a silicon atom or in terms of the Planck constant which, as far as experiments have revealed, are fixed.

The switchover is likely to happen in 2014 after more subatomic experiments. This would mean the primary standard would either be a silicon sphere or weight designed for use on a watt balance.

‘In addition to platinum and gold alloys we are looking at several other materials with regards to next generation mass standards including nickel alloys, silicon, iridium, stainless steel and tungsten,’ says Davidson. So even if the current IPK becomes obsolete, the new UV–ozone cleaning method could still prove useful for keeping the next generation of reference masses stable. ‘The cleanliness of the standard is critical, particularly when transferring from air to vacuum where the change in the mass – mainly due to water sorption – will depend on how clean the surface is,’ he adds.

No comments yet