And that’s it for today

Thanks for joining us. We’ll be publishing a feature length story on the prize next week with interviews with all the main players, so look out for that. In the meantime you can find all our Nobel prize news, comment and features here.

4.52pm Got questions? We’ve got answers.

Our explainer goes over how lithium-ion batteries work, what the new laureates did to earn their prize and what’s next for battery technology.

3.40pm We got one!

Look out shortly – on @ChemistryWorld and @RoySocChem https://t.co/1IGPmKnqH6 – for an interview we've just done with @NobelPrize winner John Bannister Goodenough. What a man - 97 and in incredible form after learning of his #NobelPrize2019 win. pic.twitter.com/w6yzFLNYsl

— Edwin Silvester Ⓥ (@edwinsilvester) October 9, 2019

2.45pm Read all about it

Our news story on the Nobel prize is live and we’ll also be posting an explainer shortly on why this work was rewarded today, what contributions each of the three scientists made and how the lithium-ion battery has changed the world.

1.03pm I think he’s happy!

12.29pm More reaction from senior chemistry figures

“I’m absolutely delighted that John Goodenough, Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino have been awarded the chemistry Nobel prize for the development of lithium-ion batteries.

“As we know, these batteries have helped power the portable revolution and now have a crucial role in electric vehicles to lowering emissions and improving air quality.

“In my view, this award is long overdue and it’s great to see that this important area of materials chemistry has been recognised.”

Professor Saiful Islam, Department of Chemistry, University of Bath

–

“I remember well when John, then in Oxford, did his pioneering work on the lithium cobalt oxide cathode. We were all impressed by this typically imaginative and creative piece of solid state chemistry; but none of us realised that the discovery would have global impact by changing the way we live and work”.

Professor Richard Catlow, Professor of Catalytic and Computational Chemistry, Cardiff Catalysis Institute, School of Chemistry

12.39pm And as chance would have it…

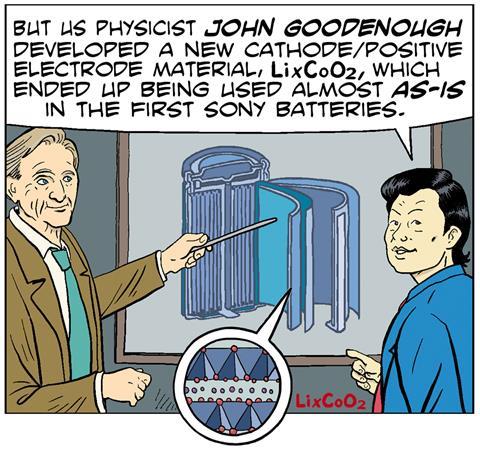

We have just published our comic celebrating lithium for the International Year of the Periodic Table. It looks at the creation and refinement of lithium-ion battery technology, featuring Yoshio Nishi (he could easily have been named on the Nobel), Akira Yoshino and John Goodenough.

12.25pm Better batteries

Goodenough’s lab pioneered lithium cobalt oxide as a battery cathode. Paired with a graphite anode, lithium cobalt oxide is the go-to cathode for smartphones and tablets. Demand from big battery makers, electronics manufacturers and auto companies, however, is putting pressure on cobalt supplies that are already under strain because of economics, politics and geography. Read our feature on the new battery chemistries and recycling schemes trying to dodge those supply issues.

12.19pm Mystery solved

Well that clears up why the Swedish academy had trouble getting hold of him – Goodenough’s not at home but in London to receive the Copley Medal from the Royal Society. What a prize giving event that will be tonight – Goodenough getting the oldest scientific award in the world after having got the most prestigious one earlier this morning. The Copley Medal was first awarded in 1731 and comes with a mere £25,000 – peanuts compared with £700,000 for the Nobel prize. No sign of Stanley Whittingham yet…

12.13pm Reactions starting to come in

Professor Dame Carol Robinson, president of the Royal Society of Chemistry, said: “Firstly, congratulations to all of the recipients of this year’s prize. Their pioneering research is everywhere you look and a great example of how chemistry has paved the way for everything from the mobile phone in your pocket to the electric vehicles and home energy storage of the future.

“It’s not the end of the journey, as lithium is a finite resource and many scientists around the world are building on the foundations laid by these three brilliant chemists.

“It’s important to recognise that this research was originally fundamental – John Goodenough conducted much of his initial research when he was head of inorganic chemistry at the University of Oxford, so this is good recognition for UK science. It is now vital that governments and funders around the world continue to support the creative, discovery science that can provide a truly sustainable future for energy.

“John Goodenough is coming to the Royal Society this evening as he’s been awarded their Copley Medal, so there’s a celebration to which I’ve also been invited to receive their Royal Medal, and I’m delighted that I’ll get the chance to meet him.”

12.05pm Cutting room floor

Nice thread on everything that didn’t make it into Neil’s interview with Goodenough.

I'm now just going to tweet some of the stuff from my Goodenough interview that didn't make the article:https://t.co/wI9FolvrLe

— Neil Withers (@NeilWithers) October 9, 2019

11.56am Nice tribute to Goodenough here

‘He’s a fantastic scientist. He has been working in this field for many, many years, and he never retired, so he’s still working in this field, up until this age. He’s still going to the lab pretty much every day, as far as I know, and he’s still making contributions to the community when it comes to battery science and battery development. So he is a really remarkable person, he is really burning for this field and really made very large contributions.’

Olof Ramström, Linnaeus University

11.44 Good prediction

Our features editor, Neil Withers, has had a personal run-in with John Goodenough’s work while writing up his PhD – more on that later! But he was also an early booster for Goodenough for the Nobel prize back in 2008 he claims. And he has evidence too.

OK, I'm going to go there with a massive I TOLD YOU ALL ABOUT GOODENOUGH IN 2008:https://t.co/uP4eylvPmX (3rd comment) pic.twitter.com/KZY8h7SLja

— Neil Withers (@NeilWithers) October 9, 2019

You can find Goodenough, Whittingham and Yoshino on plenty of other people’s Nobel predictions lists too, such as ChemBark, Curious Wavefunction and just about every poll taken (see below).

Clarivate (or Thomson Reuters as it was then) had Whittingham and Goodenough down in their 2015 hall of citation laureates too.

11.23am Stay tuned

We’ll be putting our story up on the worthy winners later today and an explainer on who the winners are, what they contributed and why their discovery is so important to be worthy of a Nobel prize (finally).

11.21am Where is Goodenough?

Apparently, even the Swedish academy of sciences haven’t been able to get in touch with him yet, so he may not know he’s even won the prize.

11.16am Goodenough takes record

John Goodenough is indeed the oldest person to ever becom a chemistry laureate at 97 and the oldest science laureate ever too. The record was previously held by one of last year’s physics Nobel prize winners, Arthur Ashkin. He was 96 years old when he won the prize.

11.11am Great news

A well deserved chemistry Nobel prize that so many people have been clamouring for for such a long time. Lithium-ion batteries have revolutionised society by providing a relaible technology to keep laptops, mobile phones and so many other microelectronic gadgets going. They’re now ubiquitous and the world is looking to them to power our transport and help us drive down carbon emissions to fight climate change.

11.01am Battery technology

Goodenough has spoken with us a number of times over the years. We recently featured him in profile where he told us he just wanted to be an explorer. We’re also got a long read on his work creating the lithium-ion battery.

We’ve also profiled Akira Yoshino, one of the other ’fathers of the lithium-ion battery’.

10.57am Goodenough finally good enough

At 97 John Goodenough becomes the oldest chemistry Nobel laureate, possible the oldest laureate ever – we’ll be checking that shortly.

10.50am Lithium-ion batteries take it!

I never would have expected it. Lithium-ion batteries has been talked about for so long as a contender but so many thought their time had passed. Congratulations to John B. Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino.

The 2019 #NobelPrize in Chemistry has been awarded to John B. Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino “for the development of lithium-ion batteries.” pic.twitter.com/LUKTeFhUbg

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 9, 2019

10.44am Ready to go

We should be starting in a minute. Haven’t heard about any delays from the academy.

10.39am Questions, questions

If you’re eager to test your chemistry Nobel knowledge while we wait you can do a very brief quiz on the Chemistry Views site.

10.36am Movement in Stockholm

Any minute now…

10.29am ‘Okay, who’s the schnook?’

We’ve had a couple of chemistry laureates tell us what it’s like to receive a call from Sweden – Ben Feringa one of the 2016 chemistry winners and Richard Henderson, one of last year’s winners, rejected the first call, before walking out on a meeting to take a second call. And the Nobel Prize Foundation has compiled a list of amusing stories. ‘Who’s the schnook?’ was what 2010 chemistry laureate Martin Chalfie asked himself when he visited the Nobel Prize website one morning in October. ‘I got to the Nobel Prize site and I found out I was the schnook!’

Other favourites include Richard Ernst having the captain find him during a flight to tell him in person that he’d won the Nobel prize!

10.23am Anyone’s phone ringing?

Secretary General, Göran K. Hansson, and the office phone are making history again. Who are they calling? #NobelPrize #Chemistry pic.twitter.com/FZpQ6IHF8B

— Vetenskapsakademien (@vetenskapsakad) October 9, 2019

10.19am Feringa Building

Winning a Nobel prize doesn’t just get you a bike parking space. It can get you a building named after you. Congratulations to Ben Feringa – work has just started on the Feringa Building.

How is your day? We don’t want to brag but ours includes a tiny Feringa Building sandcastle and the city’s most delicious petit fours pic.twitter.com/aTnm33nw60

— Feringa Lab (@FeringaLab) September 18, 2019

(Although perhaps Niels Bohr, 1922 physics laureate, was given something even better – Carlsberg gifted Bohr a house next to its brewery with free beer on tap.)

10.11am Eyes on the prize money

The Nobel prize was the biggest prize of its kind when it got going – this year’s prize medals also comes with SEK9 million (£730,000). That the Nobel Foundation has been giving such large awards for over a century is down to Alfred Nobel leaving SEK1.7 billion for the setting up of the prize. As you can see now, however, the Nobel prize award has been overtaken by some big-spending newcomers, but the Nobels must surely still be considered the most prestigious science prize out there.

10.07am Past performance can be a guide to future results

The Lasker Awards have often been good predictors of Nobel prizes over the years, being highly prestigious awards in the biosciences. Given that the chemistry Nobel prize now reward discoveries in biochemistry more than any other field (more on that later) the Lasker’s have proven a good predictor for both the medicine and physiology prize and the chemistry one too. This year the basic research prize was given for the discovery of two classes of lymphocytes – B and T cells – to Max Cooper and Jacques Miller, which ‘launched the course of modern immunology’. The clinical research award went to H Michael Shepard, Dennis Slamon and Axel Ullrich for the development of Herceptin, the first monoclonal antibody that targets cancer. The award for Shepard, Slamon and Ullrich might have been a good bet for the medicine and physiology Nobel prize – if we hadn’t seen George Smith and Gregory Winter take one half of the chemistry prize last year for work that led to the development of monoclonal antibody drugs.

To prove the point that the Lasker Awards can be a good predictor of medicine and physiology or chemistry prize success, you need look no farther than Monday’s medicine Nobel prize. In 2016, William Kaelin, Jr, Peter Ratcliffe and Gregg Semenza won the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award for their work on how animals’ cells can sense and adapt to changes in oxygen. On Monday William Kaelin, Jr, Peter Ratcliffe and Gregg Semenza won the physiology or medicine Nobel prize for their work on how animals’ cells can sense and adapt to changes in oxygen. Let’s see what happens this year…

9.56am Bikes are the new cars

One of the traditional ways in which universities honoured their Nobel laureates was a parking space in a prime location at the institute. The University of California, Berkeley seems to have started the practice and with the institute laying claim to 48 Nobel laureates it’s no wonder they have rows of parking spaces.

But it seem the times they are a changing with many carbon conscious laureates choosing to cycle to work now. One of last year’s chemistry prize winners, George Smith at the University of Missouri, was given a space in a bike rack. He’s not the first either. Ben Feringa, a 2016 chemistry Nobel laureate, was given his own spot in a bike rack too.

Thank you @NobelPrize, for sharing our video of our Nobel Laureate Ben #Feringa's new parking place! https://t.co/Hd77bNY1EH pic.twitter.com/9Cttc8sZ5w

— University Groningen (@univgroningen) August 25, 2017

Berkeley even dedicated a bike rack spot in 2016 to the winners of the 2007 Nobel peace prize – the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

However, 2013 chemistry Nobel laureate Michael Levitt told us that he didn’t even get a parking space at Stanford after winning the prize. There’s no special parking spots for laureates at Stanford, apparently, a source of irritation for prize winners there when they see what their neighbours further up the bay get given.

9.44am Good for science?

Are the Nobel prizes a worthy celebration of science or a distortion of the way that science really works in the 21st century? The prize can only be given to three people tops but these days huge teams working around the globe are behind the important work that wins the prizes. Philip Ball takes a look at whether the Nobels are still relevant in this day and age.

9.41am How can I win a Nobel prize?

Want to know what it takes to win a Nobel prize? Or how the judging panel makes its decision? We talked to Bengt Norden, who served on the chemistry Nobel prize panel for a decade, about the controversies, calamities and claims that never quite made it.

9.33am Phone home

Well this is just adorable. Monday’s physiology or medicine Nobel laureate, Gregg Semenza, on the phone to his mum after just winning the prize.

Nothing like that call from mom on your big day! #NobelPrize winner, Gregg Semenza receives a congratulatory call from his mother. pic.twitter.com/jYLyDo6zT6

— Hopkins Med News (@HopkinsMedNews) October 7, 2019

9.25am Moving for work

Many Nobel laureates are immigrants. They’ve migrated to other countries and carried out their prize-winning work there – this is because science is a global enterprise and no one country can claim that they’re doing the best work in every field. Our digital producer, Chris Pink, has put together a great video showing where future laureates were born, where they migrated to and when they won their prizes. Enjoy!

9.21am The other Nobels

Just as there is day and night, yin and yang and E and Z there are also the Ig Nobels. The irreverent counterparts to the Nobels recently had its award ceremony and answered many questions that no one has ever asked, such as how much saliva does a five-year-old produce in day, how hot is a naked French postman’s scrotum and do live cockroaches stay magnetised longer than dead ones? The research that first makes you laugh and then makes you think is always worth a read.

9.12am Gazing into the crystal ball

As usual there have been plenty of predictions on who will win the Nobel prizes this year. Data crunching, based on citations, done by the team at Clarivate has been used to make their forecast. This year they’ve tipped Rolf Huisgen and Morten Meldal for developing their eponymous cycloaddition reactions, Edwin Southern for the Southern blot, and Leroy Hood, Marvin Caruthers and Michael Hunkapiller for protein and DNA sequencing and synthesis.

Over at Chemistry Views they’ve been running a poll on who the chemistry community thinks will win and they’ve had over 600 votes so far. The consensus building (if you can call it that – the vote is pretty fragmented) is that the winner will be a male, biochemist from Europe (doesn’t narrow it down too much). Potential laureates with the most votes include Ewine van Dishoeck, Shankar Balasubramanian and Krzysztof Matyjaszewsk – only one of them is a biochemist though.

And the lovely people over at C&EN have recorded a webcast with Lauren Wolf and Laura Howes and special guests Jess Wade and Alison Narayan discussing, among other things, who might get the Nobel nod.

Stuart Cantrill at Nature Chemistry has re-run his poll on who will win the next chemistry Nobel prize. My vote went to ‘something else’.

OK, let's re-run the #chemnobel poll from last year. Has the opinion of #chemtwitter changed? What topic do you think *will* (not should) garner the prize? (Leave comments suggesting what might win if none of the options in the poll...); RTs appreciated!

— Stuart Cantrill (@stuartcantrill) September 26, 2019

8.59am Face-off

While we took a look at the data to calculate who was the average chemistry laureate, Yuen Yiu at Inside Science took a look at their faces to get an average. The end result is a little bit unsettling… (Click through to the article to see the average female laureate face created from 18 winners (out of 20 altogether) across all three science prizes.)

I "averaged" the faces of 500+ #Nobel laureates and got three eerily similar faces that reflect the historic demographic trend in #STEM: https://t.co/ZAoPkCyhpp #RepresentationMatters #Physics #Chemistry #Physiology #Medicine

— Yuen Yiu (@fromyiutoyou) October 1, 2019

8.53am And the next winner will be…

By taking a look at the data we can make a (somewhat irreverent) prediction about who the next chemistry Nobel laureate will be. Going on past trends the laureate will be male, named Richard, John or Paul and 58 years old. He will be a US citizen and working at either Harvard University or one of the 10 University of California campuses. Their prize winning work will have been published, on average, 17.5 years ago in either JACS or Nature, and the median citations for their chemistry Nobel prize winning paper will be 529. Remember though folks, past performance is not a predicator of future performance!

8.48am That’s a mean chemist

We’ve done a bit of number crunching on Nobel prize data. We can reveal that the mean-citation chemistry laureate is Sidney Altman, Montreal, Canada, 1989 ‘for [his] discovery of catalytic properties of RNA’ with 1780 citations, the closest to the mean of 1867.

The median-citation chemistry laureate is Paul Flory, Stanford, US, 1974 ‘for his fundamental achievements, both theoretical and experimental, in the physical chemistry of the macromolecules’ with 529 citations.

8.38am A Nobel prize for biology?

A bit more data viz for you. In recent years there has been quite a bit of whingeing and complaining from some corners that the chemistry Nobel prize is now a prize for biologists. Here you can see the breakdown of which chemistry subfield a laureate was working in when they won the prize. There has indeed been a rise in the number of laureates that are biochemists, overtaking organic chemistry laureates decisively in 2009 and they don’t look like they’ll lose pole position any time soon. But perhaps this isn’t so surprising given recent advances in structural determination techniques, sequencing, and drug discovery and development. Chemistry has simply become more inclusive – I think that’s something to celebrate. Discuss!

8.30am The data behind the Nobel prizes

We’ve spent quite a bit of time this year wrestling with over 100 years of data from the Nobel Foundation looking at who and what wins a chemistry Nobel prize. I’d thoroughly recommend checking it out. If you’ve ever wondered who the oldest laureate is, the institute that can claim the most Nobelists or which Nobel prize winning paper has received the most citations then you’ll want to take a look. There’s also an awesome interactive map of the world showing where every single chemistry Nobel laureate was born and the institute they moved to to do their prize-winning work.

8.25am Nobel diversity

Five women have won the chemistry Nobel prize since it got going in 1901. That’s so few that I can remember them and quickly rattle them off without even looking them up – Curie, Joliot–Curie, Hodgkins, Yonath, Arnold. Over at Nature NewsElizabeth Gibney has an interesting interview with secretary-general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Göran Hansson, to see what impact measures to improve the diversity of Nobel prize nominees have had so far. (This year’s medicine and physics prizes have gone to six men…)

8.18am Nobel in numbers

As usual we’ll start off with a few quick facts:

- Chemistry prizes: 110

- Chemistry laureates: 181

- Women laureates: 5

- Youngest laureate: 35

- Oldest laureate: 85

John Goodenough is hotly tipped to win year-after-year for his work on lithium-ion batteries, and if he were to get the nod he’d be the oldest person to win the chemistry prize by 12 years.

8.14am Stay in touch

The press conference is expected to start at around 10.45am UK time (11.45am CET), barring any problems contacting the new Nobel laureates. You can watch the proceedings unfold at 10.45am over on the Nobel Foundation’s website. We’ll be tweeting from @ChemistryWorld all things Nobel prize related and recommend the #chemnobel hashtag to keep up with what people are saying. If you have any tips or things you’d like to share then the best way to reach us this morning will be on Twitter.

8.09am Welcome everyone

Thanks for joining us this morning in the run-up to the Nobel prize. We’ll be talking all things Nobel prize related as we await the announcement and sharing our thoughts on who might win, does the prize still matter in this day and age, and what happens when you get the call from Stockholm?

A quick recap on how things stand so far: the physiology or medicine prize went to work that unearthed how cells can sense oxygen on Monday and the physics prize on Tuesday for the discovery of exoplanets and cosmological evolution. (If those two discoveries in the physics prize don’t quite gel for you as a single prize the Nobel Foundation grouped them together under the banner ‘our place in the universe’). Today is the big one (for us anyway), so stick with us while we bring you the latest news, gossip and comment on the prize. (PS We’ve also gathered all our Nobel prize stories into a single handy place for you.)

No comments yet