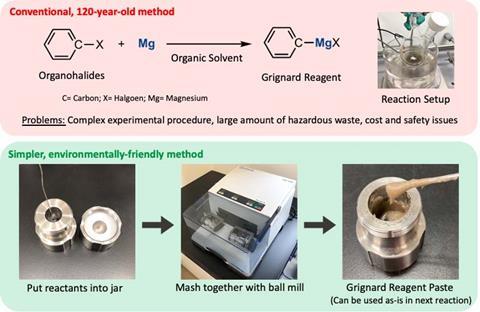

Researchers at Hokkaido University, Japan, have discovered a new method to prepare Grignard reagents using mechanochemistry – and what’s more these reagents aren’t destroyed by air. ‘It’s easier and faster,’ says Deborah Crawford from the University of Bradford, UK, who was not involved in the study. ‘I would now employ [this] method if I was to need a Grignard.’

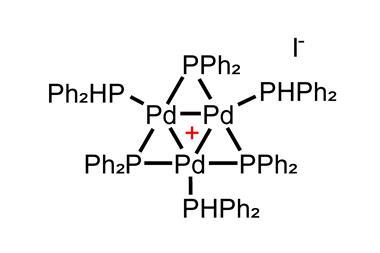

Grignard reagents are organomagnesium compounds widely used in organic synthesis for their versatility to create new carbon–carbon bonds. However, their preparation often requires controlled temperatures, dry solvents and protection from air and moisture through inert-air methodologies like Schlenk lines. ‘This is the first example of Grignards [being] prepared under ambient conditions … it’s remarkable,’ says Crawford.

The Japanese team’s secret weapon was mechanochemistry – grinding reagents together using a ball mill. While other researchers had studied the reactivity of organohalides and magnesium in these conditions, this team took it a step further. ‘We found that [adding] small amounts of [tetrahydrofuran] efficiently promoted the formation of Grignard reagents,’ explains Koji Kubota, who co-led the study. ‘The set-up is really simple: a stainless-steel ball, an organic halide, magnesium and THF [all] added into the milling jar. Then you just press start.’

The entire procedure works in air. Furthermore, the prepared Grignard reagents undergo subsequent reactions without additional purification. The researchers showcase an excellent reactivity scope for the reagent, Crawford says. The mechanochemically made magnesium compounds work in carbonyl additions, cross-coupling reactions and many more reactions. ‘Some of the transformations [they] demonstrate are difficult with conventional [chemical synthesis],’ she says. Eventually, these Grignards do spoil in air. However, this is not an issue, argues Crawford, as chemists often use Grignard reagents immediately.

Beyond the practical advantages, Kubota says this method is greener – reducing the need for special precautions is ‘highly beneficial from an environmental and economical perspective’, he says. Evelina Colacino, an expert in mechanochemistry at the University of Montpellier, France, values the ‘simplicity … and utility of this protocol’. She also remarks how mechanochemistry broadens the scope of traditional chemistry. ‘It offers access to new molecules … giving the possibility to prepare compounds inaccessible [with] solvent-based processes,’ she adds.

The new mechanochemical synthesis is optimised to prepare 1g of Grignard reagents. However, before bothering with bigger batches, the team plan to study the long-term stability of these compounds – beyond oxygen and moisture, carbon dioxide also spoils them, explains Colacino.

Crawford wonders if exploring twin screw extrusion – a technology used in large-scale mechanochemical preparations – might accelerate the scale-up process. ‘We could [then] see the biggest economic and sustainable savings,’ she says. Kubota confirms their team is currently investigating stability issues, as well as the potential of ball-milled Grignards for commercialisation.

References

R Takahashi et al, Nat. Commun., 2021, 12, 6691 (DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-26962-w)

No comments yet