Dubbed ‘molecular drill bits’ because of the way they penetrate bacterial cell membranes, anti microbial peptides (AMPs) have been of interest for several years, says Georges Belfort from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who presented the work at the 247th ACS National Meeting & Exposition in Dallas, US. ‘These are small peptides – around 10–50 amino acids long – that are produced in nature by all kinds of organisms including humans,’ says Belfort. ‘The question we wanted to ask is can we rationally design them for use against specific bacteria?’

In 2012, Belfort came across a paper published by a different group, who had used a bioinformatics process to filter information on promising AMPs from papers and databases.1 Belfort’s team used this method to gather information on what kinds of AMPs might be effective against TB. ‘Peptides that are about 13 amino acids long, which is half the thickness of the bacterial membrane, work well, so that was the size we decided to go for,’ says Belfort. Composition-wise the peptides must include positively charged residues, as well as hydrophobic regions. ‘Bacterial membranes are negatively charged on the outside, so you have to have a positive charge,’ he explains. ‘Mammalian cell membranes are neutral, which is why they are not attacked very easily by these peptides. You also need to have some hydrophobicity to get into the lipid bilayer and disturb it.’

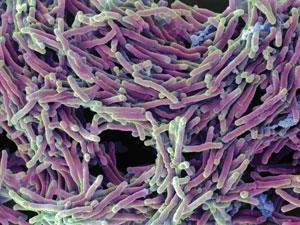

Taking these factors into consideration, Belfort and his colleagues were able to carefully choose and position each amino acid in their peptides. They constructed three new AMPs this way, all of which killed M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis, a fast growing analogue of TB, in tests. One AMP was more effective than the others, and also killed Escherichia coli cells. The group have applied for a patent for the methodology and the three peptides they made.

‘In the ongoing battle against emerging antibiotic resistant bacteria, antimicrobial peptides represent a potentially powerful new class of antibiotics,’ says Monique van Hoek, who works on AMPs at George Mason University in the US. She adds that applying this database filtration approach to other bacterial species will help improve understanding of how AMPs work and the importance of different properties such as charge and hydrophobicity.

No comments yet