Scientists have peered inside a gold nanoparticle, answering key questions about the mysterious Au-S bond

Researchers in the US have taken a snapshot of the inside of a gold nanoparticle, shedding crucial new light on one of chemistry’s longest-standing questions: how does sulfur bind to gold?1

For centuries it has been known that gold, one of the most inert of metals, will react with sulfur and that sulfur-containing compounds will bind to gold. Theories abound about how this can occur but to date there has been little solid evidence to support any of them.

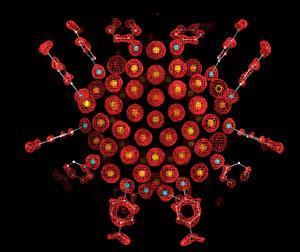

Now a team led by Robert Kornberg from Stanford University in California has solved the atomic structure of gold nanoparticles coated with the sulfur-containing compound p-mercaptobenzoic acid, revealing the nature of the bond in unprecedented detail.

’Gold atoms are zero valent and in general do not want to participate in bonding to other atoms,’ said Robert Whetten of the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, co-author of a commentary on the work.2 ’For years people have speculated about the nature of the bonding between gold and sulfur, but we have had to wait until now for the photograph.’

Kornberg’s group successfully prepared gold nanoparticles of a uniform size - something that has so far proved elusive and which itself represents a key breakthrough as it confirms gold nanoparticles have a well-defined structure, rather than simply being random colloidal agglomerations of atoms.

The team then resolved the geometry and internal structure of the nanoparticles using x-ray crystallography and showed that each nanoparticle contains 102 gold atoms, 23 of which bind to thiol sulfurs of acid molecules.

But exactly how these gold-sulfur complexes bond to the metallic gold beneath is unclear. The bond distance is longer than that between other gold atoms in the nanoparticle, suggesting a comparitively weak interaction that is still strong enough to prevent detachment.

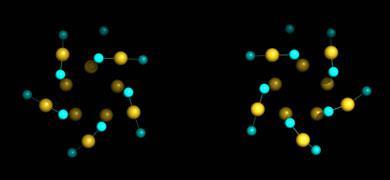

The nanoparticles also proved to be chiral - mirror images of each other.

’This work will have a big impact,’ Whetten told Chemistry World. ’It closes the door on many previously open questions. And in chemistry, once a compound has been prepared and its structure is known, it opens the way for people to start exploiting it because they know they are not going down a blind alley and wasting their time.’

Mathias Brust of the University of Liverpool, UK, is a pioneer in the fabrication of thiol-stabilised gold nanoparticles. He said that the new work represents ’a major step forward in the field’.

He told Chemistry World: ’X-ray structures of metal clusters and other nanoparticles have been determined before, but the materials were not of the same general interest as thiol-protected gold nanoparticles, which have attracted tremendous research interest over the past decade with an unusually wide and diverse range of potential applications including molecular electronics, sensors, catalysis, biomedical diagnostics and drug delivery.’

Ian Robinson of University College London said that the work was ’clearly very important’ and provided a rare example of surface science inside a crystal. ’It is a significant achievement to obtain a sufficiently monodisperse size distribution of nanoparticles that it can crystallise. The growth of a crystal would be quickly blocked by even a small fraction of wrong-sized particles,’ Robinson told Chemistry World.

The structure disproves certain earlier ideas of the gold-thiol interface and suggests a partially covalent character to the bonding. ’This structure is easily accessible to density-functional theory calculations, which could establish the stability of the proposed sulfur binding configuration,’ Robinson added. ’It is to be hoped that such a calculation will be attempted very soon.’

Simon Hadlington

References

1 P D Jadzinsky et al., Science3182 R L Whetten & R C Price, Science318, 407 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1142441)

No comments yet