Drug design takes account of known mutations

A treatment for drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been approved for use in the US. The milestone will lead to mass-produced treatments for other drug-resistant viruses in the developing world, its creators claim.

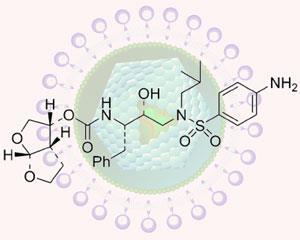

The drug, TMC-411 or Darunavir, was developed by Arun Ghosh and colleagues at Purdue University, West Lafayette, US. It is taken as a pill and is a variation on a protease inhibitor.

Ghosh claims his drug is superior to other protease inhibitors on the market because it has fewer side effects and works at a much lower dose. It is also a smaller molecule than other protease inhibitors, he said. ’We designed this molecule top to bottom to interact with the protease backbone and deactivate the virus,’ Ghosh said. ’This allows it to continue to be effective as the virus mutates, when other treatments would fail.’

Protease is a key enzyme in the HIV reproduction process. Protease inhibitors are target-specific, and the HIV virus mutates quickly to become resistant to such specific treatments. To combat this, new molecules have to be developed constantly. Around half the HIV patients who initially respond to treatment develop drug-resistant strains and stop responding to treatment within eight to 10 months, Ghosh said. He claims to have created a ’conceptually different’ class of protease inhibitors. The inhibitors interact extensively with protease, including hydrogen bonding to the protein backbone of the HIV-1 protease active site.

Darunavir has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, but is not the first of its type to be approved, said Keith Alcorn, editor of Aidsmap, an HIV information website. Darunavir stands out because it is the first to be designed from scratch, he said. ’The difference with Darunavir is that the design process for the drug took a lot more account of existing drug-resistant mutations and tried to design a molecule which was deliberately structured in order to overcome resistance to other protease inhibitors,’ said Alcorn.

Other companies are developing similar drugs. Abbott labs, Illinois, US, has been designing a protease inhibitor in preparation for the time that HIV is bound to develop resistance against its two existing products, Kaletra and Norvir, according to Alcorn.

Even Darunavir will need to be replaced one day, said Alcorn. ’It’s too early to tell if people develop specific resistance to Darunovir, but one has to assume that people can develop resistance,’ he said. ’There is no doubt that Darunavir is going to make an important contribution to HIV treatment over the next few years,’ he added.

’There is always going to be a need for new HIV drugs,’ said Alcorn. These will come, hopefully, from drugs that attack different targets in the virus life cycle. Three new classes of drugs are in development now: integrase inhibitors, CCR-5 inhibitors and maturation inhibitors. Alcorn is optimistic that within the next two or three years these new drug classes will offer three more therapeutic options to HIV patients.

Ghosh said his drug-design strategy will aid mass production of similar drugs. ’Keeping costs down greatly increases the accessibility of the drugs to Third World countries where the epidemic is worst,’ he said.

Katharine Sanderson

No comments yet