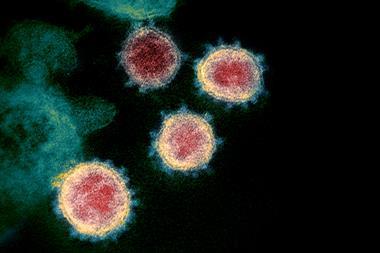

Across the world businesses, organisations and individuals are taking extraordinary steps to support the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. The effort spans multinational chemical and luxury goods suppliers, distilleries, 3D printing services and university technicians. Together, they’re addressing shortages in the most in-demand items: hand sanitiser, personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators and diagnostic tests.

Essential equipment

Universities are lending a hand by donating PPE to hospitals from labs that have been closed down by Covid-19 quarantine measures. It seems an obvious way for universities to assist, but communication channels between the two communities are not well-established. In York, the effort was started when a PhD student in the archaeology department reached out to the chief nurse for the York Pandemic Ops Group.

Simon Breeden, York’s chemistry department operations manager, volunteered the chemistry department’s stores as a central collection point. There, they gathered everything from items of PPE and cleaning products to tea and coffee for staff. ‘This was very much led and delivered by technicians across the campus, both in a multitude of academic departments and professional services,’ says Breeden.

‘Because we pooled items from many departments, we managed to get a reasonable size delivery. Even the library supplied boxes of disposable gloves used to handle rare books,’ says David Pugh, a teaching fellow in the department of chemistry. ‘We contacted the hospital and said we would hold on to the stuff until they needed it, but they replied within the hour and said – rather scarily - “send it now”,’ Pugh adds. They collected over 150 sharps bins, more than 1000 boxes of gloves, 200 boxes of syringes and 200 boxes of needles, as well clinical waste bags, aprons, eye protection masks, disposable clothing and surgical masks.

Currently such efforts in the UK appear to be ad hoc. In the US, however, a number of more organised initiatives have sprung up, including PPE Link, #findthemasks and Donate Your PPE. Equipment manufacturer Genius Lab Gear has been trying to help connect these efforts with chemistry labs, explains the company’s founder, Derek Miller. ‘The healthcare professional community and scientific research community don’t have a lot of overlap on social media,’ he says. ‘So we took it upon ourselves to aggregate the information and use our platform and friends with larger followings to help get the message out.’

Wash your hands

Universities are also trying to ensure sufficient supplies of hand sanitiser. In particular the University of East Anglia’s Health and Social Care Partners have been sharing World Health Organization (WHO) recipes for home-made sanitiser, the simplest of which is composed primarily of ethanol and glycerine.

At the request of Public Health England, the University of Birmingham has converted its Collaborative Teaching Laboratory (CTL) to produce hand sanitiser for Birmingham’s social care workers. ‘We have gathered our supplies of isopropyl alcohol, ethanol, hydrogen peroxide and glycerol to make hand sanitiser in line with the WHO’s guidelines and we are working rapidly to get the first batches out,’ says Emma Melia, director of operations at the university’s College of Engineering and Physical Sciences.

Technicians at the University of East Anglia (UEA) are also making hand sanitiser gel, which they have already started distributing to NHS organisations in Norfolk. They are currently producing around 170 litres a day. However, UEA vice-chancellor David Richardson notes that these quantities cannot continue without a serious boost to the ethanol supply as they are currently relying on local producers’ generosity. He has written to UK health secretary Matt Hancock asking him to review the tax duty on alcohol and ensure ethanol producers don’t have to incur the costs.

Among those producers are distilleries, who are using the ethanol they usually make for beverages to make hand sanitiser instead. These range from well-known brands such as Pernod Ricard and BrewDog, to boutique distilleries like Psychopomp in Bristol, UK. BrewDog has already provided sanitiser to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary’s Intensive Care Unit and agreed free distribution to the UK’s National Health Service and various charities.

Yet many companies don’t have ready access to the glycerine required, creating a bottleneck in their process. ‘We initially got some using Amazon while they were still sending stuff out,’ says Psychopomp founder Danny Walker. ‘But once Amazon scaled back with their deliveries, we started having to use companies that manufacture glycerine. We’ve got 25 kilos of it arriving from somebody in Liverpool on Thursday.’

Other companies, such as French luxury goods brand LVMH, which makes perfumes including Christian Dior, Givenchy and Guerlain, have ready supplies of ethanol and glycerine. LVMH has transferred the company’s perfume factories to producing hand sanitiser, explains spokesperson Sophie Arnold, which it will supply to the French health authorities free of charge.

In the UK, petrochemical giant Ineos is a leading producer of glycerine, ethanol and isopropanol. It has announced that it will build a hand sanitiser plant in Middlesbrough, UK, in just 10 days, with a capacity of a million bottles per month. It will do the same in northern Germany, and provide the product free to hospitals. ‘Ineos is a company with enormous resources and manufacturing skills,’ comments Ineos founder and chairman Jim Ratcliffe. ‘If we can find other ways to help in the coronavirus battle, we are absolutely committed to playing our part.’

Tom Brophy, managing director Western Europe for Croda, says his company is also working with customers ‘that are manufacturing hand sanitisers, giving them additional stocks of glycerine as they increase production’. ‘We are well connected with government and industry bodies and are increasing this contact to identify any areas where our expertise could be used to support the management of the outbreak of COVID-19,’ he adds.

One of the most acute equipment shortages is in ventilators – vital equipment to help those with the most severe cases of Covid-19. On 16 March, the UK government called on the country’s manufacturers to register their ability to help in an effort to boost the country’s existing ventilator stock, which some estimates put at 5000, up to around 30,000. Engineering giants like Dyson, Airbus and Vauxhall have all reportedly sought to join this effort.

The ventilator producer Smiths Group based in London, UK, announced that it is scaling up production. By contrast the ventilator maker Penlon said it was waiting for the government to provide its requirements. A spokesperson for the High Value Manufacturing (HVM) Catapult, which spans seven centres in England and Scotland, says it is coordinating these larger companies ’to confirm designs, confirm supply chain and help to ramp up production’. They also explain that the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Cabinet Office have contracted PA Consulting Group to go through the thousands of offers of help from smaller companies.

There has been some excitement over whether 3D printing might be able to rapidly provide components. 3D printing companies Isinnova and Lonati in Brescia, Italy, and the local FabLab were able to produce cheap replacement valves for ventilators. But Josef Průša of 3D printing company Prusa Research in the Czech Republic, suggests that this might not be the optimal strategy for respirators. ‘None of the [3D printing] designs available right now have been tested to ensure they provide the protections needed, at least none of the ones I am aware of,’ he wrote in a blog post. Prusa Research has focused on producing face shields to protect health workers instead.

According to the HVM Catapult spokesperson ‘everything’s on the table currently’, including 3D printing. ‘It will depend on exactly the material used for 3D printing … Until anyone producing medical ventilators gets sign off from the regulatory body that will be guaranteeing standards, then nothing will go ahead.’

Regulation wrangles

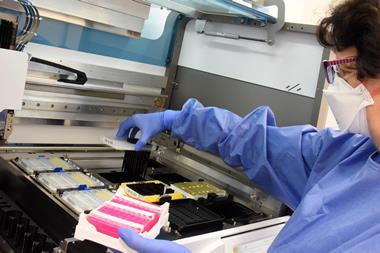

Regulatory issues have also delayed the UK’s adoption of a polymerase chain reaction based Covid-19 test from UK biotech company PrimerDesign. But on 12 March, Public Health England placed a £1 million order to supply eight hospitals for four weeks. Company spokesperson Achilleas Neophytou told Chemistry World that it is now supplying 50 countries with its test. Fortress Diagnostics likewise announced the availability of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Elisa) test for Covid-19 on 9 March but is yet to announce receiving orders.

To address similar delays affecting another area, the European Chemicals Agency (Echa) has offered disinfectant manufacturers the chance to temporarily sell new products without meeting European rules. Several European countries have already relaxed their rules, while Echa is also developing a centralised process to offer this benefit in several countries at once.

Their doing so is just one more way that people in many professions are adapting in unprecedented ways to help society weather the Covid-19 pandemic.

No comments yet