Levels of toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) released into the environment could be higher now than they were during peak production in the 1970s. Despite being banned for over 40 years, new estimates suggest that significant amounts of these carcinogenic chemicals are inadvertently being formed as byproducts of other chemical processes.

The researchers from the UK and Canada say that their ‘back of the envelope’ calculations – which they admit could overestimate the scale of the problem – warrant further investigation and that byproduct PCBs should be reconsidered as emerging pollutants of concern.

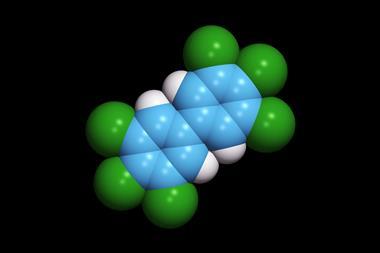

PCBs are synthetic chemicals that were once widely produced as commercial mixtures for industrial applications until they were recognised as a hazard to both the environment and human health in the 1970s and 80s. This led to a global-phase out and strict regulations on their production, use and disposal.

However, most investigations have focused on PCBs specific to commercial mixtures and little attention has been paid to minimising or eliminating byproduct PCBs, which are inadvertently produced in certain chemical and product formulations such as pigments and dyes.

‘We’ve been advocating for quite a while the need to do analysis of all 209 PCBs,’ explains lead research David Megson, reader in chemistry and environmental forensics at Manchester Metropolitan University. ‘We’ve got very well documented records of commercially made PCBs because they made it as a product [so] they knew exactly what it contained … [but] the more we looked through the data, the more we were finding random PCBs popping up that didn’t make sense.’

Using PubChem, the researchers searched for the production volumes of 69 different chemicals and chemical classes that had previously been reported to have the potential to generate byproduct PCBs. Limited by the available data they focused their attention on production in the US in 2019, multiplying production volumes of 45 of the chemicals/chemical classes (the ones they could find data on) by the permitted PCB byproduct concentration limit to give the potential maximum mass of PCBs per year.

They estimated that around 43,000 tonnes of PCBs could have been legally produced in the US in 2019. This, they said, exceeded the maximum annual production of 39,000 tonnes of PCBs by the US agrochemical giant Monsanto in 1970. However, the authors acknowledge that this could be an overestimation.

The analysis also highlighted that although the pigment industry was under ‘intense scrutiny’ for PCB byproducts it may actually be responsible for less than 0.1%, or around 340 tonnes, of the total potential PCB production. The researchers said more work was needed to establish which PCBs are present in other chemicals/chemical classes to provide a more robust estimate of the potential scale of the problem.

‘We banned this chemical, everyone thinks it’s a thing of the past … but they’re only measuring the dominant PCBs in the old commercial mixtures, so of course they’re going down because we’ve not been using [them] for 40 years, but all these other ones may have been going up, and we have been completely blind to this,’ explains Megson. ‘I’m hoping this research is going to stimulate people to go out and start looking at a variety of different chlorinated solvents and products to identify the true scale of this issue.’

However, Keri Hornbuckle, an environmental contaminant expert at the University of Iowa in the US, said Megson and colleagues have made some ‘major assumptions’ about byproduct PCB production. ‘The assumption [is] that chemical manufacturing industries of any kind that have a potential to release byproduct PCBs are releasing [them] at the level that the [Environmental Protection Agency] in the US allows,’ she says. ‘In my view that’s not realistic, because there’s no data, that I’m aware of, that backs that up.’

She did agree that not enough measurements had been made of enough products to understand the breadth of potential industries that are producing these chemicals. ‘Somebody should try to figure out all the industries that use those particular processes; you need a catalyst, you need to use an aromatic solution like a solvent; chlorine has to be present.’

Keri also agreed that categorising byproduct PCBs as emerging contaminants of concern would ‘draw attention’ to the ways that PCBs have been ‘ignored’ in the past and ‘force’ industry to remove them. ‘The authors point out that many studies are done with indicator PCBs instead of measuring all 209 PCBs. Many studies only measure a small number and that results in not measuring these byproduct PCBs at all. Many studies that do that miss this story entirely.’

References

D Megson, IG Idowu and CD Sandau, Sci. Total Environ., 2024, DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171436

No comments yet