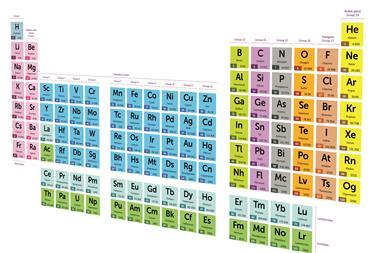

It may not be the most Christmassy of the entries, but a miniature metal construction made by students at a science club in Didcot Girls’ School in the UK has been named the overall winner of a competition for chemistry-themed Christmas trees – or chemistrees. It impressed judges with its original design and construction from chemical elements – just in time for the start of the International Year of the Periodic Table.

The tree’s twisted metal wire trunk and branches support multi-coloured foliage made of various salts. It incorporates several different elements – the entry says it is made from copper, sodium, boron, oxygen and hydrogen, coloured with traces of iron, copper and manganese.

The competition organiser and lead judge John O’Donoghue, a Royal Society of Chemistry education coordinator at Trinity College Dublin, said the winner may be a ‘controversial choice’, but its uniqueness made it stand out. ‘We thought it was by far the most unusual one out of all the entries,’ says O’Donoghue. ‘It has redefined what a chemistree needs to look like and clearly took a lot of time to make. It’s also got a lot of different [chemical] elements, which is kind of what we were looking for.’

This year’s competition saw chemistry enthusiasts around the world go head to head to construct trees with the theme of ‘the periodic table’ in preparation for the International Year of the Periodic Table that starts in 2019. Some adorned real trees with glassware-inspired ornaments, while others built festive retort stand constructions and jazzed them up with flasks of colourful solutions.

While Didcot Girls’ School’s metal tree won the competition overall, winners were named in five other categories. In the ‘paper-based tree’ category students at a UK secondary school won with a tree built from paper cubes bearing element symbols.

A colourful arrangement of round-bottom flasks from chemists at Simon Fraser University in Canada was named top in the ‘purist chemistree’ category, where entries must be built solely using lab-based materials.

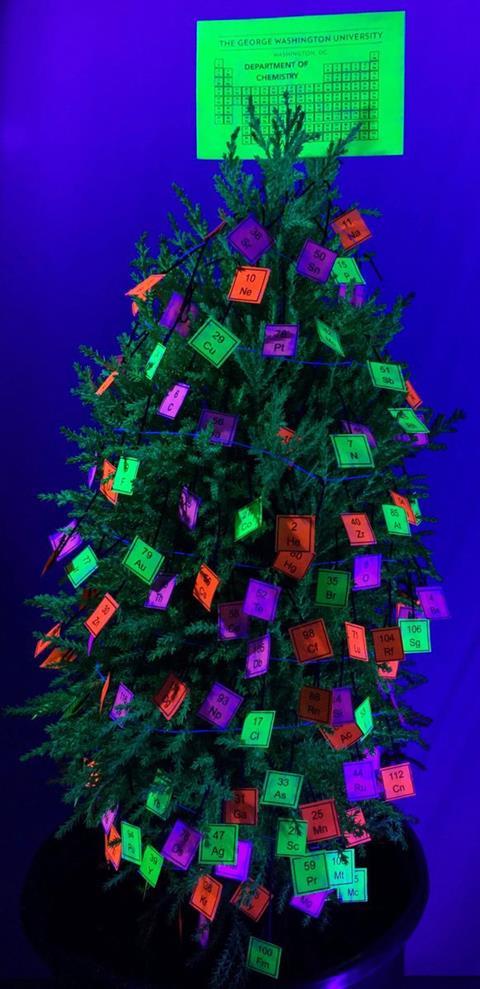

The winner of the most ‘chemified’ Christmas tree, where real trees are decorated with a chemistry theme, went to Erik Rodriguez, an assistant professor of chemistry at George Washington University, who created a fluorescent chemistree by dying the tree with strontium aluminate with europium and decorating it with anthracene dyed thread.

For ‘cross over’ trees which combine traditional Christmas ornaments like tinsel with lab equipment Stephanie Rathsack at Wyoming High School won with an original mix of clamps, glassware and a silver-mirrored bottle on top.

@johndhodonoghue #Chemistree @wyohonorschem #wyohchem Materials-ring stand and clamps, glassware with green liquid, light strands & bulbs, silver bottle lab tree topper. Ornaments-student created representing an element and it's properties or uses. Video here. Photos 2nd tweet pic.twitter.com/ROlKDh4W7N

— Stephanie Rathsack (@mrsrathsack) December 14, 2018

In the category for crystal, nanoscale or molecular model-based trees William Barron de Burgh, a chemistry teacher at Dame Elizabeth Cadbury School, created an electroplated chemistree.

#chemistree

— Mr BdB (@WRBdB) December 8, 2018

Draw a design with permanent marker on copper sheet. Attach it as the cathode and place in zinc sulfate. Lots of fun with Y11 electrolysis.@johndhodonoghue @chem13news @RealTimeChem #chemed pic.twitter.com/1D8Esn2qa3

A rundown of all the winners and honourable mentions in each category can be found on the O Chemistree blog and further chemistrees can be found be on Twitter under the hashtag #chemistree.

Bizarre underworld

O’Donoghue tells Chemistry World he has been running his chemistree competition for ‘nine or 10 years’ and it began as a small, inter-lab contest when he was still a PhD student at University College Cork in Ireland.

‘Some of the labs in college used to make them. And I kind of started wondering where did this come from? Why do chemists put together these weird trees?’ he says. ‘It turns out there are some published [journal] articles dating back as far as 1940 describing chemistrees. It was just this sort of bizarre underworld of creative chemistry that had been going on for a long time, but there wasn’t any one place you could go to find these things.’

The competition began on Facebook, but is now held on Twitter, where anyone can enter by tweeting pictures to O’Donoghue using the hashtag #chemistree. The winners in each category are chosen by O’Donoghue and a guest judge who assess each entry separately then meet up to compare notes. This year’s guest judge – chemistry teacher Ger O’Donovan from Regina Mundi Secondary School in Cork – has experience judging chemistrees having run similar competitions among his own students.

O’Donovan says the competition is a great activity for students ‘because it gets them to consider equipment and solutions in different ways … and connects schools and universities throughout the world’.

No comments yet