Executives face down international controversy over tax schemes and previous post-merger record

US pharma giant Pfizer is battling a backlash of suspicion and hostility across the world over its attempts to acquire its UK-headquartered rival AstraZeneca (AZ). Pfizer’s ongoing efforts, after AZ rejected an increased offer valued at £63 billion, are bringing its tax affairs and actions following previous mergers under intense scrutiny. Although Pfizer has said AZ’s currently reluctant directors must unanimously recommend the deal for it to go through, chief executive Ian Read is still enthusiastic. ‘By combining these two companies we… strengthen the ability to bring products to patients,’ he said in a video presentation. ‘We strengthen the financial aspects of the company. We can invest in science. I see this as a win-win for society, a win-win for shareholders, and a win-win for stakeholders.’

Read initially contacted AZ privately in November 2013, before suggesting a shares-and-cash deal worth £46.61 per AZ share in January 2014, valuing it at £58.8 billion, which AZ turned down flat. On 26 April, Pfizer repeated that offer privately, was again rebuffed by AZ, but then made a public approach on 28 April.Pfizer raised the potential offer to £50 per share on 2 May. Under the UK’s City Code on Takeovers and Mergers, Pfizer must now decide whether to make its offer official, or take it direct to AZ’s shareholders, by 5pm on 26 May.

The two companies’ pipelines fit well together, Read asserts, and he hopes to unite their development of cancer, cardiovascular and inflammation drugs. He also believes the combined organisation will be more efficient, helping meet demands for lower cost medicines. ‘One way of doing that is to consolidate and take out overlapping functions,’ Read says.

Tax incentives

The deal would also ‘liberate the balance sheet and tax of the combined companies’, according to Read. 70–90% of Pfizer’s cash is held outside the US at any given time, and its year-end 2013 balance sheet recorded reserves of $49 billion (£29 billion). If its foreign subsidiaries pay the cash to the parent company, that money becomes taxable by the US government. The merged company would therefore make its tax base the UK, which doesn’t tax companies for bringing cash home. UK corporation tax is also set to fall to 20% in 2015, compared to the 27% Pfizer expects to be paying in 2014. The ‘patent box’ that the UK is currently phasing in lowers tax on profits from patented products developed within the UK even further, with the final rate set to hit 10% in 2017.

So far, AstraZeneca’s board has not given Pfizer the approval it needs, instead remaining focused on chief executive Pascal Soriot’s strategy to overcome patent expiry challenges. ‘The pipeline we have has changed dramatically over the last 15–18 months, and the entire team is totally focused on delivery,’ Soriot told a conference call on 6 May. ‘Any distraction can certainly have a big negative impact… I have been in a sufficient number of mergers to know there can be a tremendous impact.’

Political football on drugs

Nevertheless, politicians in the UK, US and Sweden are concerned what will happen if Pfizer forces through a deal. US senators like Carl Levin want to close the ‘tax loophole’ Pfizer plans to exploit, while Maryland and Delaware’s state governors have written to Ian Read over possible job losses. Meanwhile, Read has written to UK Prime Minister David Cameron with assurances, including keeping at least 20% of any combined company’s R&D workforce in the UK and retaining ‘substantial’ manufacturing in Macclesfield. In response the Wellcome Trust, the country’s largest independent research funder, also wrote to Cameron, demanding he find ways to hold Pfizer to these promises. Read and Pfizer’s executive team have subsequently repeated those commitments during grillings by politicians on two separate House of Commons committees, saying they are legally binding for at least five years.

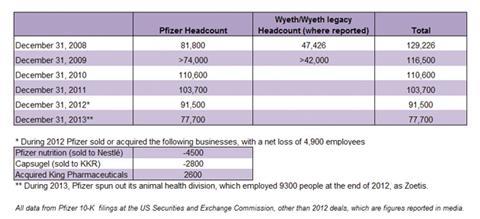

Job concerns arise following Pfizer’s acquisitions of Warner-Lambert in 2000, Pharmacia in 2003 and Wyeth in 2009. It subsequently closed research sites in Kalamazoo and Ann Arbor, Michigan; Skokie, Illinois, and planned to close its Sandwich, UK site, although it has maintained some employees there. In 2008, before Pfizer acquired Wyeth, the two companies employed a total of around 129,000 people. According to its filings at the US Securities and Exchange Commission, by the end of 2013 Pfizer had terminated around 37,000 (29%) of those jobs. Acquiring and selling off various units has led to net loss of a further 11% of the pre-merger employee total. However, all big pharma companies typically cut 20–30% of their headcount over that period, with AZ itself reducing its workforce by 20% from 65,000 in 2008 to 51,500 in 2013.

The House of Commons Business Innovation and Skills committee questioned a similar reduction in R&D investment. Pre-merger, Pfizer and Wyeth spent $11 billion, but now Pfizer spends $7 billion. ‘The $11 billion goes to $10 billion because of some of the divestments we’ve made – the animal health and nutrition business,’ explained Frank D’Amelio, Pfizer’s chief financial officer. ‘Then quite frankly we looked at the therapeutic areas where we felt we could bring most value to patients, and so we exited certain therapeutic areas.’

Outlook unsettled

Despite the controversy, Richard Littlewood, founder of healthcare and life science consultancy appliedstrategic, says ‘the post-merger situation will present a stronger platform for innovation’. ‘The deal is both exciting commercially – it offers potentially a way forward for AZ – but also challenging as it presents the greatest test of the value of AZ R&D,’ he tells Chemistry World. Littlewood, who was formerly a director in Wyeth’s European haemophilia business, adds that he expects ‘another premier league merger and many deals in the other divisions’ in the next five years.

A former Pfizer executive, still working in the pharmaceutical industry but who wished to remain anonymous, disagrees that such megamergers are beneficial. ‘The more complex the integration, the harder it is to achieve synergy targets,’ they say. ‘Innovation outcomes get worse, bureaucracy increases, payors and consumers suffer due to arbitrary price increases. The size of these megacorporations breeds inefficiency and ineffectiveness. Pharma also has the option of breaking itself into smaller constituent pieces, to create more customer-centricity, less bureaucracy, more nimbleness and agility, greater competition, finally allowing new business models to emerge over time.’

No comments yet