Restructuring increases as generics boom approaches

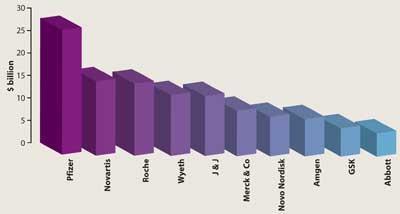

With the cutbacks announced by pharma companies in 2008 - and the looming spectre of more to come - one could be forgiven for thinking that it’s all doom and gloom in the sector. But that’s not the case. Admittedly, drug companies are cutting back on their operations, from research to sales, but big pharma is better placed than most industries to weather the credit crunch. Most large companies have substantial cash piles (see chart, below), built up to mitigate against potential lawsuits after product withdrawals. So they are not as exposed to the vagaries of the credit market - and well placed to snap up smaller biotech rivals at reduced prices to replenish their pipelines before their big sellers fall foul to generic competition. Conversely, the biotechs themselves are left with few alternatives, as investment money has all but dried up.

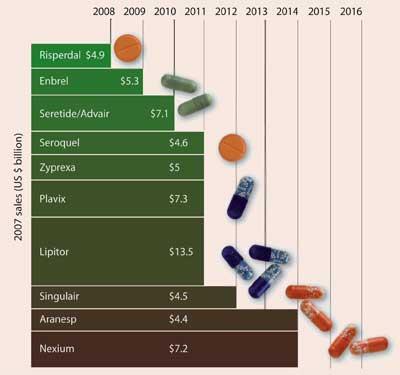

According to Datamonitor’s head of companies’ analysis Chris Phelps, the impending patent ’cliff’ (see chart, facing page), where many big-selling drugs go off-patent between 2011 and 2013, is already factored into share prices. Investors are taking a renewed interest in companies with strong balance sheets - like pharma. ’Companies are sitting on a lot of cash, and the price of potential acquisition targets is falling. The cash is worth the same it was six months ago, so they can now buy companies on the cheap,’ he says. ’This all ties in to the patent expiries in 2011-2013, as there’s not enough time now to push products through their own pipelines. If they don’t have something big in Phase III, now it’s not going to offset those declines, so late stage acquisitions look a good strategy.’

While there were no mega-mergers in 2008, there were a number of smaller takeovers. Some of these were indeed pipeline-filling exercises, such as Eli Lilly’s $6.5 billion (?4.3 billion) takeover of cancer specialist biotech ImClone. Novartis’ $880 million acquisition of Speedel was particularly interesting. Speedel was set up by ex-Novartis employees to develop the renin inhibitor aliskiren for treating high blood pressure, which Novartis had decided not to pursue. It was eventually commercialised as Tekturna/Rasilez, with Novartis as a marketing partner. Once the regulatory hurdles were cleared, Speedel was snapped up.

Generic expansion

Many companies have started following Novartis’ diversification into the generics market, which saw it set up its Sandoz business unit in 2003. Japanese company Daiichi Sankyo is buying India’s Ranbaxy for $4.6 billion, while Sanofi-Aventis is hoping to take over Czech company Zentiva for $1.96 billion. And, as long as it passes competition regulations, Israeli company Teva will take over its US rival Barr, to create a generics powerhouse to rival Novartis’ Sandoz. Even Pfizer’s generics business, which has so far focused on creating generic versions of its own drugs, has hinted it is looking to start making copies of other companies’ off-patent drugs. GSK is taking a slightly different tack - rather than building up its own porfolio, it has signed an alliance deal to sell generic products from South Africa’s Aspen Pharmaceuticals in emerging markets.

Reorganising for success

It’s getting ever more difficult to discover new blockbuster drugs that will make huge profits - many indications are now well-served by cheap generics. And even when potential blockbusters do reach the market, there is no guarantee that they will provide the hoped-for returns. When Sanofi-Aventis’ weight loss drug Acomplia (rimonabant) was approved in Europe in June 2006, there were high hopes it would be a big seller. Yet the US Food and Drug Assocation (FDA) refused to license it, citing reports of severe depression, and in October the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) pulled it from the market saying its benefits no longer outweighed its risks. It was the end of the line for the whole class of drugs, too -Merck, Pfizer and Solvay stopped developing their drugs that all targeted the CB1 receptor.

Many companies are slashing staff numbers, a trend that looks set to continue as pharmaceutical companies aim to cut costs to mitigate the looming revenue losses. Several firms are changing their research structures and are refocusing their therapeutic area portfolios. GlaxoSmithKline, for example, has subdivided its research operations into small ’drug performance units’ which have to compete for funding. In the process it has cut 1200 R&D jobs across its sites in the UK and the US. It is also closing its manufacturing site in Dartford in 2013, with the loss of 620 jobs, and a further 200 are to go at Barnard Castle, in County Durham. This site makes the antiemetic Zofran, which loses patent protection in 2009. Meanwhile, AstraZeneca is closing three manufacturing plants and cutting 1400 manufacturing jobs as it moves much of its manufacturing to China.

It’s not just GSK which is changing its research focus: several other companies are concentrating their efforts more on potential big-selling fields such as cancer and diabetes, and pulling out of areas where the market is small or there are strong generic products. Pfizer announced that it is to stop research in several areas and focus its efforts in speciality areas such as cancer, diabetes and regenerative medicine which are poorly served by generic competition. Those areas earmarked to go are osteoarthritis, anaemia and most surprisingly heart disease - the area that gave birth to the world’s biggest selling drug Lipitor (atorvastatin), which had 2007 sales of over $11 billion.

Wyeth is reducing its therapeutic portfolio from 14 to just 6 fields, including cancer, vaccines and metabolic disease, and from 55 to 27 diseases. Merck & Co, meanwhile, says it remains committed to heart disease, but will lose a further 7200 employees by the end of 2011, and will shut three research sites. And Belgium-based UCB is losing 2000 jobs - about a sixth of its workforce.

Not all pharma firms are painting such a bleak picture of the future - at its annual R&D update, Schering-Plough predicted that as many as seven of the 75 drugs in its pipeline could become blockbusters in the near future. According to Fred Hassan, Schering-Plough’s CEO, the company’s strong drug development pipeline and low exposure to patent expiries could set the company apart from the rest of the pharmaceutical industry.

Quality control

While increasing amounts of research and manufacturing are being outsourced to India and China, concerns are growing about product quality from cut price manufacturers. This year, the US FDA seized numerous batches of the blood thinner heparin from China after several people died. They had experienced a severe allergic reaction, which was put down to oversulfated chondroitin being present in the heparin. The FDA also accused Indian company Ranbaxy of falsifying data and deviating from good manufacturing practice standards at two of its plants, halting production of more than 30 medicines made there.

The answer to this will lie in more frequent inspections to meet the growing amount of manufacturing in Asia. ’There are 100 plants in India that are subject to FDA inspection and, to be frank, we don’t go there often enough,’ says Michael Leavitt, US Secretary of Health and Human Services. ’We are opening three offices in China, and one in India. We have to change the way we do things - would it be more logical and efficient to split the inspection up [between different agencies] and share the information? If we fight the change [in the way medicines are made] we will fail.

Sarah Houlton

No comments yet